When making “Cane Fire,” Anthony Banua-Simon could surely draw on his filmmaking instincts, but he found his mind wandering to another artistic medium as he began weaving together a spellbinding look at his family’s history and that of their home of Hawaii, depicted in hundreds of movies before but never like this.

“I grew up sampling found audio, almost like hip hop production, and when I would read about producers that I was influenced by, they would call it an alchemy when two samples were gelling together,” says Banua-Simon, of being able to jump between the past and present. “They could get these goosebumps, especially if it’s a hip hop beat, it’s this whole new energy, and that’s totally what I’m feeling when I edit, it’s like this active flow of conversation.”

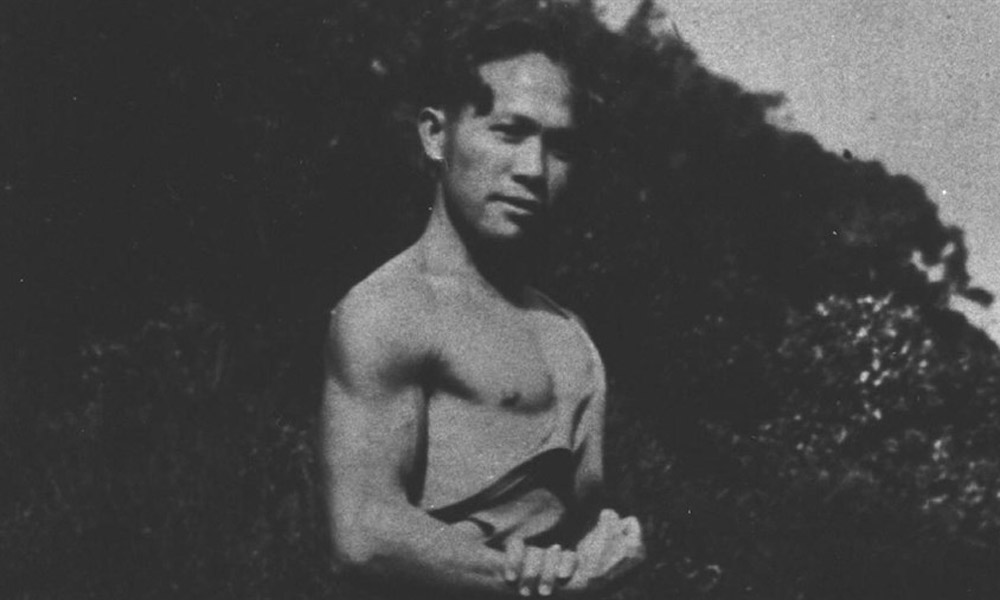

In the case of “Cane Fire,” it’s a long overdue conversation that feels vibrant in the hands of Banua-Simon, who considers the long history of the islands’ outside forces lining their own pockets without much of the proceeds going to local residents. The director didn’t need to look far for details, telling of his own great uncle Henry Bermoy, who witnessed first-hand the shift from one form of economic exploitation in the region to another as a descendant of Filipino workers lured to Hawaii to work in the sugar cane fields, achieving significant progress towards equitable working conditions with increasing union organization until the islands achieved statehood in 1959 and the powers that be reallocated their investments into tourism where they could pay the same workers considerably less as hospitality staff.

However, even as compelling as Bermoy’s individual story is as well as that of the Coco Palms Hotel, a contentious location in the present day after the once-grand hotel has been devastated in a hurricane and its land is up for grabs between redevelopers and locals who insist they have claim to it, “Cane Fire” is equally fascinating in how Banua-Simon interrogates how Hollywood was enlisted to put on a glamorous facade for a brutal business, eventually becoming impenetrable to attack as a fantasy destination in most people’s minds. The film becomes at once a comprehensive survey of both labor and the film and television industries on the islands while repositioning the images of them both to see them anew and the result proves to be revelatory. Following its virtual debut at Hot Docs last summer and a win for Best Documentary Feature at Indie Memphis, “Cane Fire” is now starting its national rollout and Banua-Simon was kind enough to talk about the origins of the project, putting the personal history of his family into a greater context and the discoveries he made along the way.

How did this come about?

I was in a documentary residency in Brooklyn, and we were doing short documentaries about the surrounding neighborhood. This is like South Williamsburg. It’s two mile radius, and Mike Vass, my co-producer and co-writer on “Cane Fire,” and I did a short documentary about the Domino Sugar Factory, which is this large brick building on the Williamsburg waterfront that’s still there today, though it’s been closed since 2004. We were doing research about it and we found two former workers, brought them to the space, and they’re giving the context of the industry at the time. This giant brick building produced half the nation’s sugar at one point, and had this long history of this strong labor force, and a strong union at the time — there was one of the longest strikse in New York’s history for about two years that both the workers participated in and we really inspired this history we didn’t know about.

I was doing more research on the history of the sugar trade and these large businesses and I found that my great, great grandmother from Puerto Rico was actually working in the sugar fields that was extracting sugar to this refinery. The first US and state governor of Puerto Rico at the time orchestrated her immigration to Hawaii because there was a hurricane and knocked out the sugar fields in Puerto Rico, so part of my family story started there with her daughter meeting my great-grandfather from the Philippines in Kauai and I was following that sugar history, knowing that my great uncle Henry was driving trucks for the mills and my grandfather, Henry’s brother, grew up on the plantation camps for the pineapple and sugar industry. So it really started with him. He lived through this really long period, being involved in all the shifting industries on Kauai and it branched out from there.

I really didn’t know where it was going to head. It was a personal project, self-funded, whenever I had time, I would go there [to Hawaii], just by myself with a camera and follow both the material history, collecting these oral histories, but also the representation through Hollywood productions and realizing there was more of a motivation and a history to why films were constructed the way they were. [It was] almost creating this parallel timeline of the Hollywood history with my family’s material history — four generations, starting with my great-grandfather to my cousins who are about my age now.

It seems like there could’ve been a temptation to do a strictly archival documentary when the material there is so rich, or vice versa when your family history is so interesting. Were these ideas intertwined from the start?

I did a lot of first-hand research and I could have just kept in the archives, and there was a side of me at first [where I thought] I can do just an archival [documentary] or an oral history, but I felt that these interviews I was conducting were really informing the research and would sometimes bring a new perspective that I wouldn’t have had if I just kept the distance and assumed the story had already been told. There were these different elements that commented on one another and I would bring them in whenever they felt relevant. So many conversations were circumstantial — we wouldn’t know if a film meant something to somebody or they were conflicted [about] nostalgia or their opposition or involvement with something, so you never knew where it was going to go, but I always kept it as something I wanted to bring together. And you have the larger mass media productions and then also first-hand archival of actual documentation [of] the sugar plantations in this era — so using those things and balancing how to tell the story straightforward or circumvent or re-contextualize material was a tricky balance.

A really compelling thread becomes the protests over the fate of the Coco Palms. Was that actually coincidental with your project or did you know about it going in?

Yeah, it was one of those things where I did not predict the occupation or the restoration when I started the project. In fact, when you see the tour that’s being led through the space of the hotel, I filmed there first before I met the activists. Again, I knew of the history in an abstract way [with] the historical records, but I couldn’t find a way to manifest anything that [could] happen before the camera, so that was really unique with the activists. I started filming in 2014, and I didn’t start filming with activists until about 2018, so it was exciting to have so much of the film happen in the past [with] the historical records, but then having people acting upon the past and manifesting something new before my eyes and not knowing where it was going to go. And it’s still it’s ongoing now [as] an open conversation in Kauai.

Was there anything that happened that changed your ideas of what this could be?

Yeah, actually doing research, I came across particular periods that I had not seen any photo record of and I know what [these places] look like in the present day, but I just had to assume what the housing layout was after the union’s negotiated the workers being able to have their own land and build their own homes outside of the plantation housing. The new construction of that was all obscure to me — it was all in books. I was at the Historical Society, and it’s really dedicated staff, but very small, so they have tons of photos people that have passed on, but they don’t have a big enough staff to actually go through them. And there was one day when they said, “Oh, here’s this closet full of old photos. You can just go through, no one’s catalogued them. You’re welcome to just go through and see what you find.”

That’s now what’s seen in the film when you see those shots of the new developments of the housing for the plantation workers — it was the first time I’ve ever seen anything like that, and it was all just going through this old booklet of these musty old photographs and seeing it physically that made me draw the connection to the Habitat For Humanity housing [in the present day], where it was is similar style housing built on land still owned by a sugar company. Seeing both eras and new construction made me like connect the dots [made me think] “This is an interesting connection to investigate.”

What’s it been like getting this out into the world? I know it probably hasn’t been what you expected, but I know already it’s sparking conversation.

Yeah, I will be bringing it to Hawaii in person beginning of next year because I unfortunately wasn’t able to attend the Hawaii International Film Festival because of COVID restrictions and safety, so I’m looking forward to that. I think most filmmakers feel that like there’s so many obstacles to finishing a film that a new one arrives and just immediately adjusts to it and do the best you can. We’re all stubborn and we just have this drive to just get it seen somehow anyway possible.

“Cane Fire” opens on May 20th in New York at the BAMCinematek and will travel across the country including stops in Tacoma on May 24th at the Grand Cinema, Boulder at the Dairy Center for the Arts from June 1st-5th, Washington DC at the Suns Cinema on June 2nd and 7th, the Lumiere Cinema in Los Angeles on June 3rd and the Northwest Film Forum in Seattle from June 4th-15th. A full list of theaters and dates is here.