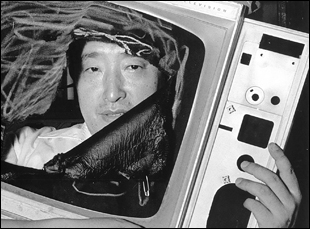

“Until I learned how to listen to him, it was hard to hear him,” David A. Ross, the former director of the Whitney Museum, can be heard saying about Nam June Paik, of whom a short time earlier in Amanda Kim’s invigorating portrait of the pioneering video artist “Moon is the Oldest TV,” another gallerist Holly Solomon jokes, “He speaks about 20 languages – all really badly.” It’s true that Paik, a citizen of the world after leaving his native South Korea to study music in Berlin upon being lured to Europe by the beauty of Arnold Schoenberg’s unconventionally harmonic compositions, never sought mastery of any specific cultural dialects in the countries that his work reached, but then again he was busy refining his own, using a camera to capture his musical experiments before becoming more enamored by its capabilities than any other instruments he might be working with.

Inspired by the boundary-breaking chance compositions of John Cage, who would let coins determine what music he’d improvise for a performance, and falling into the collective of artists known as Fluxus where he’d rub shoulders with Yoko Ono, Joseph Beuys and Jonas Mekas – none of whom would constrain themselves to thinking they were working in a single medium – Paik would embrace the possibilities of broadcast as the form was emerging from its infancy, bringing 16 televisions with him and little else upon moving to New York in 1964. With his personal written reflections read by Steven Yeun and the film’s fascinating insight into how his own upbringing amidst the ruins of the Korean War as the son of a wealthy businessman who kept his aunt as the head maid in the house forever poisoned him towards a capitalist mindset, Paik is celebrated as a visionary who could see where society was headed so clearly by standing so far outside of it and Kim makes a convincing case that the world still may not yet have caught up with Paik, but certainly leaves no doubt that his work is more relevant than ever.

Although Paik may have faced the frustration of being ahead of his time, “Moon is the Oldest TV” takes great delight in showing him challenge the power structures in front of him, no matter what form they took, fighting for credibility for a form that would ultimately become the ultimate cultural currency when his video collages and live performances with other artists can look like an early progenitor of YouTube and creating installations where a viewer could engage with a screen using magnets to twist the image they were seeing to free it from the artist’s complete control. “Moon is the Oldest TV” exudes Paik’s adventurous spirit as much as it captures it and appears bound to cultivate an entirely new generation of admirers following its premiere at Sundance earlier this year and more recently at CPH:DOX. The film is set to win over just as many new fans for Kim, who makes an auspicious feature debut after serving as a creative director for Vice, and as it begins its theatrical run across the U.S., kicking off this week with special engagements at Film Forum in New York where the director will be holding court all week for Q & As with special guests, she graciously answered a few questions from us about the project’s origins, her personal reasons for wanting to ensure Paik’s legacy and why even if she could never could properly meet the artist, who passed away in 2006, she felt his presence throughout the production.

It’s been a long journey. We started this around five years ago and it was very surprising to me that there hadn’t been a Nam June Paik documentary already, considering his importance in art history and also in Korean culture. I was really inspired by his work that I’d seen growing up and I’m an obsessive researcher when I become interested in something, so I started Googling everything about him and the more footage I saw of him in front of the camera and the more I read his writings, I just thought that he was speaking to the world we’re living in today and our generation and it was important in particular that young people knew who he was and what he was saying about these technologies that would continue to evolve and run our lives essentially. It felt pressing and that really motivated me to continue on this path in making this film.

I was trying to decide whether video art would lend itself to one of the most well-preserved archives around or one of the most difficult to reflect when many of these works were so ephemeral. What kind of challenge was it?

Yeah, when I talked to a lot of early video artists and the people who were around with the video cameras at the time,they didn’t realize this art would be historical. These half-inch tapes for the early Portapaks were very expensive, so people would record over them and there were things that clearly were not preserved and a lot of sad moments where there were damaged tapes or missing tapes. There were also amazing moments where I would be connected to someone through another friend or someone that I interviewed and they they would say, “Oh, that person was at that event that you’re asking me about, and Nam June was there. You should ask this person about this tape.” So then I would discover something people hadn’t really seen before. I was also lucky that there is an organization called Electronic Arts Intermix, and they do great work in maintaining and housing a lot of these really important video works. They have Nam June’s video collection, so that was an amazing resource and it was a little bit of an investigative journey, finding his friends throughout his very global life from the 50s onwards, but I pieced it together.

It sounded like David Koh, your co-producer must’ve been really helpful when he was once Nam June’s assistant.

Yeah, that was very serendipitous and felt fated. While I was doing this research, David and I were just hanging out and I brought up the conversation of my research and he mentioned that it was a bucket list project of his because he had been Nam June’s assistant, so we embarked on the journey together, and David was friends with Fab Five Freddy, who knew the estate and was an integral part in connecting all the dots to ensure that this could happen.

You thread this needle in such a beautiful way, but was it challenging to honor the avant garden spirit of the artist while something that was more accessible to more mainstream audiences?

That was something I worried a lot in the making of the film because one of my intentions was to make sure the film could be accessible to a wider audience that wasn’t necessarily aware of Fluxus or might not be able to relate to a film that would be too experimental without taming down too much his own avant-garde spirit. Because it’s really easy to fall into the trap of making something, especially considering how many languages [Nam June Paik] spoke, and in these beautiful koan-like riddles that you could get lost as a regular viewer without any sort of foundation of his work or ideas, so it was very important to me to synthesize it in a way that someone who wasn’t from an art historical background.

[His writing] was a really huge part of this film and also a really great way to try and get more intimate with Nam June and to get inside his head because Nam June was quite private. He wasn’t necessarily sharing everything that he wrote in interviews and he wrote constantly. He had a crazy amount of [written] archives, a lot of them stored at the Smithsonian and letters that were preserved by his friends that he sent them to, and they’re scattered all over the world, in Germany, at MoMA, in the Fluxus Collection, Silverman Fluxus Collection. I was very lucky because at the time when I was starting this project, John Hanhardt, Greg Zinman and Edith Decker-Phillips had compiled some of his essential writings, and also a mix of both personal, intimate letters to John Cage and some Rockefeller Foundation grant committee members in one book called “We Are Open Circuits,” and that was really a core element in trying to construct this film.I really appreciated how you folded in his family history, which isn’t done in an obvious way at all, as you show where his sense of rebellion came from throughout the film rather than in one introductory burst. How did that interplay come about?

I think everyone’s past and personal history, especially family, affects them in a very deep way, and it was the same with Nam June, but it wasn’t going to bring him down, so I didn’t want it to be this very heavy throughline. But it’s a reverb that continues throughout his life and it’s both a complicated relationship to Korea, the country, but also to his father and the rejection of the wealth and the way in which power was used in a way he felt was negative. And he was actually rebelling against anything that was status quo or as Mary Baumeister says, at one moment when she talks about how Nam June wanted to combine sex and music, because no one had done it before. “Why can’t sex and music be combined? He wanted to break that taboo.” That’s a throughline in all of his work, whether it’s performance, video, music, and I think that’s what makes him a great artist. He’s not defined by a medium, even though everyone knows of him as a video artist, [where] he was tremendously important, but he was also just a great thinker and wanted to break out of any sort of structure that we were socialized to believe in and had never actually thought more deeply or critically about.

Did you feel like you could reflect your own attitudes towards art through this story?

There is an element that every film is personal, and one of the things that really resonated with me was that Nam June could see both the negative and positive of this evolution of technology and how to incorporate this into his art practice. But ultimately, he was very hopeful and he was seeing possibility beyond others, and that’s maybe something that I hope to see in the world more and that I want to impart in other people is that there are always possibilities even when you don’t think there are.

Was there anything that happened that changed your ideas of what this could be?

That is the beauty and the difficulty of an archival documentary is that you can find creative ways of using these archives, but you are given these materials and you have to figure out how to best use those materials. There’s something you might be searching for and you may never come across it, but particularly in the writings, there were little seeds that I didn’t expect along the way or even in interviews [like] the moment David Ross [is interrupted by a] phone call, you see these chance accidents or happenings that were completely unexpected and I played with those.

When that scene isn’t a fluke as far as being interrupted, did you actually feel like Nam June’s disruptive spirit was around the shoot?

Yeah, I think Nam June was definitely lurking in the making of this film because we had too many weird technological issues to have not been haunted by Nam June’s ghost, whether it was the telephone or [the flickering] light stuff. At one point in the edit, the computer and everything in the editor’s house shut down and at another point, I remember we were trying to edit one of his video pieces and we weren’t sure whether we wanted to include it or not and all of a sudden, we hear Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata playing through the walls. That was one of Nam June’s favorite classical pieces, and it felt like he was speaking to us, and when we checked the room next to us, sharing that wall, there was no one there. So there were always these weird, unexplainable happenings [that made me] believe he was around.

This would seem to be a testament his enduring power in more ways than one. What’s it been like for you getting it out into the world?

I’m still processing it. It’s been a whirlwind. Sundance happened in January, and it was such a beautiful experience to share it with an audience because it makes the film really come alive and then to also share with such a different audience in Copenhagen [at CPH:DOX], [where] it’s a European audience, [and I’m wondering] how do they react? What are the things that they hold on to? It’s been really beautiful and it feels really special that Nam June would be my first feature both because he reflects my own itinerant background and concerns I have about what is happening today and I just think he’s a wonderful character and I wish I had met him.

“Nam June Paik: Moon is the Oldest TV” opens on March 24th in New York at Film Forum.