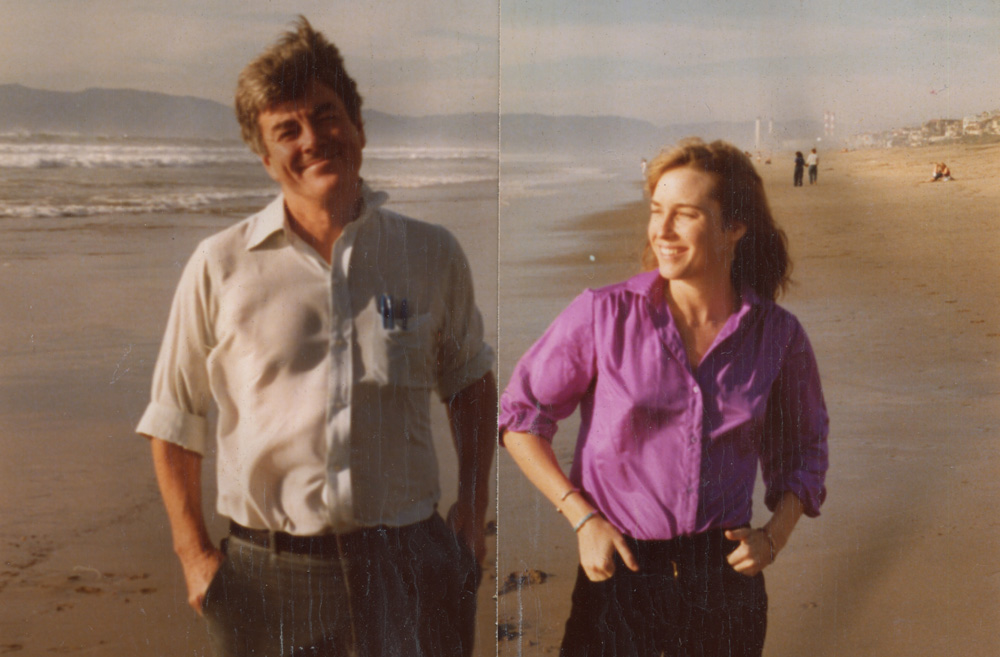

Alix Blair thought she had a good subject for her first feature “Helen and the Bear” when it came to her uncle Pete McCloskey, who in his seventies had abandoned the Republican Party he once was a prominent member of as a U.S. representative from San Mateo, California for nearly 25 years. Now during the 2016 election, he was making calls urging voters to deny Devin Nunes a seat in the area he once represented, a good two decades after he left office himself, but no less politically engaged. To profile McCloskey, Blair was always planning to include his wife Helen as part of the picture, but it wasn’t until arriving at their home where Helen now handles most of the chores and compensating for her husband in other ways as his memory starts to fade that the real story she should be following started to reveal itself to her, one that could actually all unfold in front of the camera even if much of it took place in the past.

As Blair joins her aunt to sift through journals she kept while being a politician’s wife and beyond, “Helen and the Bear” becomes a revelation beyond the story it’s telling, juxtaposing a relatively calm present for the couple with the wistful and occasionally defiant private thoughts of Helen as she figured out her role as a wife, a completely unexpected development for someone who didn’t necessarily consider marriage for herself as either because of her personal goals or her sexuality. However, finding a shared love of the physical wilderness with McCloskey, “Helen and the Bear” follows her through similarly uncharted psychological terrain as she puts many of her own ambitions aside for Pete’s professional pursuits, with short, haiku-like bursts from her journals arriving as sharp, emotional pangs as vivid as the moment they were written in, and now locked into a partnership in which she carries much of the burden as Pete, 20 years her senior, is showing signs of his age.

What has kept her in the marriage may never be verbally articulated, but then again what is spellbinding about “Helen and the Bear” is also a bit ineffable as Blair simply bears witness to the couple as they hit the road on a trip to Santa Fe and observes what makes sense about them even when little else adds up. While there is magic there, Blair offers her own as well in the presentation of Helen and Pete’s home as a safe haven and a bewitching narrative structure in which time is in a constant swirl that can make an escape futile. With its world premiere at Hot Docs this week, Blair spoke about how she worked out the sophisticated and surprising structure for the film, the thrilling discovery of the journals that made it possible and reaching the climax of a seven-year journey for her as a filmmaker.

I started making the film thinking I was going to make a short about Pete ahead of the 2016 election, and I was very much thinking it would be about politics. But like so many of my peers, you start thinking you’re making a film about one thing, and then it completely changes and as soon as I got there, and I started witnessing the relationship [between Pete and Helen], it almost immediately changed to [thinking], “Wow, I really, really want to investigate their love and to understand how did this relationship work over all these years?”

It seems like you actually spent a number of years with them as well. How long did the shoot take?

It’s been unfolding for seven years, and not every day. Many human lives aren’t exciting day to day, so you take pauses and I was taking other work. Then the pandemic was in the middle of the film making, and I stayed engaged with them during that time, and one of the big switches in what I thought I was making to what I made came when Helen shared those 40 years of diaries from when she was a young woman in her twenties until now at the end of the film when she’s 70. That just made me so curious to see how time could be such a character in the story, rather than just documenting their life as it is now, but how to bring in the past in a meaningful way.

We think we move through time in this linear way, but I perceive it in my own lived experience much more circular, like how we come back to memories and how things in our family trigger us from childhood, so I believe very strongly that we are carrying all these past selves with us all the time, and I wanted to figure out a way to evoke that through the cinematic language of the film. With the diaries, once I knew that Helen felt okay and consented to me using them, I very much wanted to make them like a character in the story as much as the human beings are characters to try to get at that feeling of time not [always] moving forward, but [roaming around] at the same time, if that makes sense.

It’s beautifully done and it becomes indicative of who Pete and Helen are in relation to one another when Helen has this rich inner life that’s expressed with the diaries and Pete has to live in the moment, deprived of his memories. Was it interesting to find a way to express that differentiation?

We were so blessed to work with Katrina Taylor, our editor who was a co-writer on the project because she was just so much a part of making the story. One thing that I struggled with in making the film is that a lot of the tension is in the past — the deep, deep complications of will this relationship continue to exist in the future? That emotional tension is impossible to get in their interviews now because it’s resolved for them, and the journals allowed me to do that when you feel the doubt and the rage and the confusion from Helen writing at that moment in time as a younger woman [about] staying in her marriage or leaving it, which was just not possible to find in interviews, even as we got deeply into the emotion. You don’t feel it the same way as the journals because the way that most people keep journals, they don’t write the happy moments, as I have found in conversation with other people that keep journals. They’re a receptacle for whatever pain or confusion [we have], so I think they are just such a living memory of a certain time in the past.

And I knew that Helen kept some journals but I didn’t know the tremendous archive that she had. We struggled over the course of the film to figure out where they were, like somewhere in a barn or hidden under her bed, so I feel like the story we were building up until the journals was very reliant on modern day verite and on archival of Pete. But once we found the journals, that blew open the structure of the film. We did partner with Emily Anne Hoffman, an excellent animator based in New York who we did a lot of initial creations that were much more like animation, like creating figures and having them move. Then I had this idea of hiring actors to play ghosts of their younger selves and I even got a couple extra shoot days with humans in my community, having them read Helen’s journals because I had this idea of having a Greek chorus. There were a lot of iterations of it, which can be such a frustrating on a doc, especially with timing and financing to have enough space to try these weird ideas that I would not say are failures. You have to go through them to figure out what the story wants and the way that the story wants to be told. But there was a lot of trying things out to see what would stick and in the end, I really wanted to retain the tangible paper feel of the way you are able to read someone else’s journals in the cinematic language.

It’s one example of many where the simplest stylistic choice may be the most sophisticated – I was extremely taken with how you are able to get so much exposition about Pete across in a clip from a William F. Buckley interview that plays on a TV – it doesn’t hide being slightly surreal when you see it on a TV in an empty room, but it plays with the idea of verite when you also present it without any differentiation from what’s come before.

It’s one example of many where the simplest stylistic choice may be the most sophisticated – I was extremely taken with how you are able to get so much exposition about Pete across in a clip from a William F. Buckley interview that plays on a TV – it doesn’t hide being slightly surreal when you see it on a TV in an empty room, but it plays with the idea of verite when you also present it without any differentiation from what’s come before.

That’s one of my favorite scenes and one that was really hard for me and Katrina to work on. Some of my absolutely favorite films in documentary are ones that move in magical realism, and I am so emotionally moved by films that do that that there was inherently a curiosity in me of, is there a place for that here? I never want to force it if it would be too disconnected from the story I’m trying to tell, but with the journals, and the verite, [I wondered] could we infuse [it with] this dreaminess? I’ve used the word ghost a lot, but with the idea of time, [I wondered] is there a way to engage some magical realism principles in this film that wouldn’t feel too jarring, [leaving an] audience to wonder where it’s coming from.

Like any art making, it’s really walking in the path that the artists before you have made and have taken risks to say, “here’s a way you can do it,” and when I start a film, I build a library or a look book, not just of films, to say, “This is my inspiration. These are my heroes. How can I use them to guide me to be the kind of filmmaker I want to be without appropriating from them?” And “Time” was one that I thought the way Garret Bradley and her editor Gabe Rhodes, [established a] friendship between the past and present was so beautiful and just challenge the audience to [feel] “Okay, this is different than just turning the camera on in present moment life.” So I gave myself, especially working with Katrina Taylor, a permission to say, “Okay, here are the few scenes where it feels like [magical realism] could be appropriate and a really joyful way to engage with the past.”

We had earlier versions of that specific scene with Buckley and the TV that were pushing magical way more, but I wanted somehow to convey that Pete, the way he lives in the past is he just relives his politics over and over. Even as his body has failed in time, his mind hasn’t and it’s hard for him because he wants to do so much and he can’t. He’s moving into his late 90s and he is still writing legal briefs. He is still writing op-eds, so with that Buckley scene, I wanted to evoke that Pete lives in this world of the past all the time.

Because Pete was a public person, was meeting him now something you had to contend with when there was this image of him out there in the archival materials?

Because Pete was a public person, was meeting him now something you had to contend with when there was this image of him out there in the archival materials?

Yeah, at one point in the film, Helen talks about how strange it is to be living with someone [where] you can have such parallel lives but you’re not interconnected. That was in the genesis of the film [a bit] when I was making this political story about Pete, [considering] how such a public figure whose life has been consumed and analyzed by the public is partnered to a person that is such a private person. I immediately became so curious of this tension of Helen, a very private person, a person that has chosen to keep lots of secrets, being partnered to a man so public and it’s something that she loves about him but something that is inherently problematic. And interacting with Pete, [you see] he is forever a politician. He is so deeply a politician in his identity that it’s actually really hard to separate the man from the public figure. He lives his life with such courage and such activism that those two things — the man he is and the politician he is, aren’t separate, whereas [with] Helen, they’re very separate. The public wife of Pete McCloskey is a very different person than Helen when she’s able to be on her own.

After living with the film yourself for some time, what’s it like to be getting it out into the world?

It feels so surreal. Most of my team is remote — the pandemic made that necessary, and choosing who I wanted to work with meant that not everybody was going to be in the same geography as me, so I have a lot of anticipatory excitement. it’s been really surreal to have this thing created that you care so much about and you’re so proud of, but then you have to wait till a festival, at least in this modern system, to bring it to an audience. I’m so honored by what Helen and Pete shared with me and I’m so grateful and I really want their story to kind of shake up what love looks like and how we do forgiveness and how we do repair in love. It feels counter to what mainstream love stories are, so I feel really joyful and I don’t think that I’m going to believe it until I’m on the airplane to Toronto.

“Helen and the Bear” will screen at Hot Docs on April 30th at Scotiabank Theatre 5 at 11:45 am.