“The time we lost isn’t the kind that can be made up,” Jess (Kalena Charlene) tells her ex Kainoa (Holden Mandrial-Santos) in “Moloka’i Bound,” a fact that that seems impossible to get around when the latter was recently released from a prison stretch and hopes to reconnect with his former partner and his son Jonathan (Achilles Holt). However, the words carry a mild irony when director Alika Maikau Tengan is making up for some of his own, having made plans to film “Moloka’i Bound” as his first feature in his native Hawaii in 2020 before lockdown made that improbable. To tell the story of Kainoa trying to put his best foot forward in restarting his life, Tengan saw the time away as an opportunity to infuse the character study with an even greater amount of grace, refining his skills as a director first on a scrappier production “Every Day in Kaimuki” while working with Mandrial-Santos, whom he first partnered with on the 2019 short of the same name, to find a deeper, richer story in the parolee’s path to redemption.

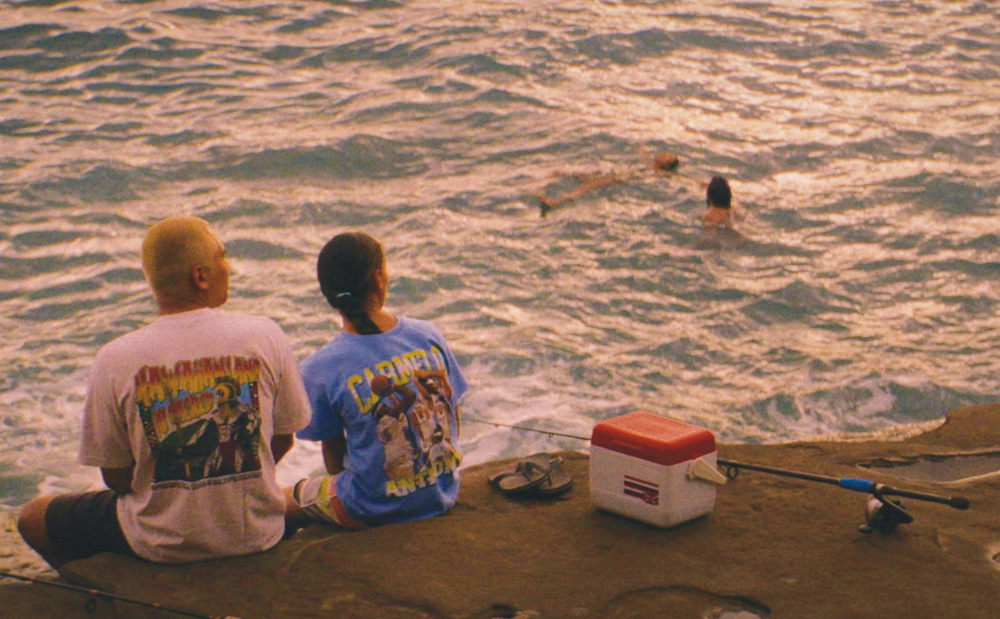

Now with two films under his belt, it’s safe to say that Tengan has already distinguished himself as a unique voice, attuned to the gentle rhythms of life on the islands, but exceptionally conscious of the water always roiling just off the shore when training his lens on the working class locals who may help prop up the image of paradise to the rest of the world but find their own lives are no picnic. In “Moloka’i Bound,” Kainoa finds a job taking tourists out on the ocean, but an escape for himself looks out of reach when only his sister Olena (Kamalani Kapeliela) looks excited to see him after disappointing most of his loved ones as a small-time drug runner. When everyone else has moved on with their lives during his time in prison, Kainoa has trouble finding where he fits in, having to reintroduce himself to people who have written him off while coming to terms with not having clear ideas about who he is, complicated further by being caught in the chasm between his indigenous roots and where Hawaii seems to be moving towards culturally, making any attempt to find his footing even tougher when the ground seems to be shifting beneath his feet.

While Kainoa struggles with his personal sense of place, Tengan summons its strongly for others as he makes sure that it’s the people of Hawaii rather than its geography that give it beauty and that what comes across as natural wonders often are the product of considerable and largely unseen labor. The director never lets anyone see him sweat as he follows Kainoa all across Oahu and ultimately to Moloka’i where his mother resides and while the film captures its main character’s restlessness, it also allows for the calm where Kainoa can perhaps find the freedom to find a way forward, offering a similar respite for audiences. With “Moloka’i Bound” having extensive travels around the world since first premiering last year at the Seattle Film Festival, it was exciting to catch up with Tengan at the L.A. Asian Pacific Film Festival where the film was making its Los Angeles bow to talk about the long road to bringing it to the screen, having to go with the flow quite literally filming on the water and the pride in seeing those around him rise to the occasion.

It was a really interesting process of working backwards because after I made the “Moloka’i Bound” short film and then I wrote the feature script, I [thought], “This will definitely be the next thing that I make.” Then of course the pandemic happened and everyone had to rethink their approach to work in general. It was a very fast pivot because when we decided we were going to make “Everyday in Kaimuki,” we didn’t have a lot of preparation time. My friend Naz, who’s the subject and star of the film, was going to move in three months, so we had to write very quickly and start shooting, even though we weren’t finished with the script. It was very catch-as-catch-can. You didn’t have a lot of time to overthink things, whereas “Moloka’i Bound” was a totally different approach because I had years to write and rewrite and for better or worse, maybe overthink certain things. When we made “Kaimuki”, it was such a small crew with just me and Chapin, my cinematographer and my sister, and with “Moloka’i Bound,” we had a more filled-out crew and a longer runway, so getting adjusted to having that, it took some time, but we found our flow in the end. I really understood the value of having so many talented artists in different departments and how that can help you realize your vision.

What was it like developing this originally with Holden?

I lived with Holden at the time that we were developing the feature film. He was great to just bounce ideas off of, and this is my third time working with him, so I had a pretty good sense of what he was capable of. Granted, having an entire feature film on your shoulders is a really big ask and I think even I was maybe not prepared for how demanding that would be, so I’m really grateful to him for rising to that occasion. The other supporting character, Kawika Kahiapo, who plays the bad influence [on Holden’s character], grew up in the same area [as Holden and I] and went to the same high school, so we knew a lot of the same characters that we were trying to portray in this film. And Kawika just thought of those sort of unsavory characters that we all knew and tried to channel that into his performance. All of the actors had really great ideas for their roles.

I wondered if many of the actors had some sort of connection to their roles — I thought Hale Natoa, the parole officer, looked slightly familiar and I realized after the fact he was actually one of the subjects of Ciara Lacy’s “Out of State.”

Sometimes the connection would come through in mysterious ways without us knowing when we cast certain people, but certainly with Hale, it’s because Chapin, the same cinematographer also shot “Out of State,” and had mentioned to me how much Hale enjoyed public speaking with the film and how comfortable he was sharing his experience with others. When Chapin told me that, I was like, “Wow, I wonder if he’d be interested in playing a role like this on the other side of it.” So I met with Hale and he’s such an amazing and kind guy and just has a presence, which I felt in that documentary. I hoped that would translate as the parole officer and it totally did. He brought so much wisdom and advice for myself in the crafting of his role and Holden’s role as well, so I can’t say enough good things about him.

Kamalani Kapeliela, who plays the sister, comes from a musical background and the moment when the character duets with Holden is a beautiful one in the film. Was that in there before casting the role or come about because she was playing it?

Yeah, I had met her as she was just performing [musically] and I was so moved by her performances, specifically of that song, “Kauanoeanuhea,” which she performs in the movie. I exchanged information with her after I saw that performance, thinking I would just use her music in the film, but fast forward to when it came time to cast the film, I reached out to her and I was like, “Hey, I know you don’t really act, but would you be interested in auditioning for this role?” And she was down fortunately. Once I knew that we were going to cast her, I tweaked the role to have music play a more prominent part in the film so that I could feature her performances because I think they’re so beautiful.

When you’re making these films about the working class, seeing the islands as they see it where there’s beauty but also hardship, is it difficult to figure out shots when you could point the camera in any direction and it looks amazing?

It is a fine line certainly not wanting to overly beautify things, and specifically where this film is set in Kaneohe where me and Holden and many of the other actors grew up, it is very blue collar. It’s very working class, so we didn’t want to dress it up too much. It is beautiful, of course, but the inner workings of their lives and the daily stresses, oftentimes it doesn’t allow you to appreciate that beauty, so I wanted that to come through.

The amount of locations are indicative of the great ambition overall. Was it difficult to pull off?

It’s funny you mention that because our producer, Nina Yang Bongiovi mentioned that this is probably the most company moves she’s been on in one production. Maybe that isn’t much of a compliment and I should’ve refined the script a little bit more, but I really like seeing the diversity of Hawaii, of not only the different pockets of Oahu, but then traveling to Moloka’i and seeing and feeling that expansiveness. It was quite stressful to shoot all of that together, but I’m very grateful for the way that it turned out.

Is it true the strip club scene where Kainoa is directly confronted with his past actually was shot in reverse from how you see it in the film where you filmed the fight first and the tracking shot entering the club last? That seems like a trying day.

Yeah, that was a big and stressful day for us. For starters, we filmed at an actual strip club and they’re open seven days a week, so the only time they allowed us to film was starting at two am to the early morning, so we got there at midnight and then we were prepping to start shooting. First, [the characters] drive the car up to the club and get out of the car, so that was the first thing we shot to like warm everybody up and then the fight scene [takes place outside], so we shot that from two am to four am. After that, we went inside the club since you can’t see any light. It’s pitch black on purpose so you don’t know what time it is in there and we knew we’d have that time in there for the end [for the entrance tracking shot]. I’m just proud of the actors because that was very demanding, especially for Holden, the lead, and Jordan, the guy he fights with. That was my first time working with a stunt coordinator with a fight choreography and I was scared that it wasn’t going to look real or good, but they killed it. I watch it now and I know it’s fake, but it’s hard for me to watch and it feels very visceral in a good way.

There’s a really cool decision to connect the action to the camera, so it really thrashes around with each punch. How did that end up coming about?

Chapin had that idea and I agree that it makes it feel more kinetic. Chapin had so many great ideas about how we could film the action in a very exciting and engaging way. We shot it about six or seven times and I remember something John Wells said to me a while back when I shadowed him on the pilot for “Ke Nui Road,” [where] he mentioned that these long oners, it’s usually around the fifth or sixth take that might be your best option. Once you keep shooting past that point, everyone starts to lag a bit, and he was right because we used that fifth take.

It was tricky. There’s a couple of scenes where Kainoa starts working on the boat, doing the tours, but the really tricky stuff was shooting the boat going to Moloka’i because we had to get up at four in the morning and be on the water to drive the boat all the way around the other end of the island to try to make it for sunrise. That was challenging and stressful in itself to make sure we got there for the right timing, but then we had a whole bunch of other scenes to shoot on the water after that, so we were on that boat for eight or nine hours. Being on the water for that long, it’s tricky. We had a follow boat as well for safety, and getting wide shots and a drone as well. Some people got seasick and I was super nervous that I’d get seasick, but thankfully I took enough ginger chews and enough Dramamine that I survived.

Then our Moloka’i-based producer Miki’ala Pescaia was trying to wrangle some horses for us and we didn’t have a lot of time left on the island. We weren’t sure when we would shoot that pivotal ending scene with Kainoa and the horses. But after we finished shooting all of our boat stuff and we were all super tired, we had gotten word that she was able to get some horses, but we’d have to shoot it when we got back on land, so it was a very demanding day for the crew and especially for Holden, because that’s such a pivotal emotional scene. He had already given so much throughout the day and I think you can really see that actually in his performance at the end where he is so exhausted. There’s an acceptance of his fate.

You mentioned seeing him shoulder a lead role – what was it like to see him pull it off after it was all over with?

Yeah, I’m super proud of him. He is in essentially 95% of the scenes, and maybe I didn’t prepare myself for how demanding of a role that it would be and how much would be asked of him every single day as the protagonist of a film. So it was a big adjustment, but I’m really proud of the way that he handled that. And no one is really professionally trained in the film. Achilles Holt, who plays [his son] Jonathan, he never flubbed a line. I was so blown away by him and that was his first major acting role and he just had such a depth. I’m just so proud of all the actors.

We’re now a year out from when this first premiered in Seattle. What’s it been like taking this out on the road?

I can’t believe it’s been a year, but I feel very fortunate to have traveled with the film around the world. I went to a film festival in Okinawa and I’m part Okinawan, so that was amazing to not only go there for the first time, but see the parallels that even the local Okinawans felt because they have a legacy of colonization and also American militarization as well. It’s one of the most fulfilling things is to see when a film relates to other people on levels that you couldn’t have possibly anticipated.

“Molokaʻi Bound” is currently on the festival circuit. A full list of screenings are here.