After filming a concert that was set to serve as the triumphant capstone to his latest short on a Friday, Trevor Anderson was one day away from the end of a week-long shoot with the musician Jesse Jams when he got a call alerting him that his subject was in the hospital, having a cutting episode after hearing voices. Despite plans to shoot a music video on Sunday, Anderson had no intention of continuing to film until Jams insisted that they should, only in a different way than they had been anticipated.

“We went to a nice spot in the River Valley in Edmonton where we could get a perspective on downtown and the inner city, looking across the river valley and Jesse just told us what happened after the concert,” recalls Anderson for one of the most powerful scenes in “Jesse Jams.” “Of course, you don’t want a film like this to be trauma porn, and you also don’t want it to be inspiration porn and it could easily have been that if it had been like, ‘And the concert was a success and now everything’s fixed.’ But Jesse really put it into this much more complex, realistic and sober context [where] as he says in the film, ‘When you have as many mental health challenges as someone like me, this is just your day-to-day and you take it as it comes and deal with it one thing at a time.”

It’s a fragility and strength that Anderson captures well in “Jesse Jams,” even amidst the hard-charging punk music that its star expresses himself with, having quite a history to draw even at just 25 years old. In and out of foster care as a teenager after his grandparents passed away, Jams’ reclamation over his own voice is particularly compelling when he deals with a host of mental health issues that were only exacerbated by his experience of jumping from one group home to another. Now out as transgender and fronting the band Jesse Jams and the Flams, he has found an outlet for many of his most torturous thoughts where he can turn them into art, but still remains in a constant struggle with his memories getting the better of him, a race that’s reflected in the energy of the frenetic 16-minute short.

While the film’s festival run was cut short by the COVID-19 pandemic, “Jesse Jams” has found its way online as a Vimeo Staff Pick of the Week, which you can watch below, and Anderson spoke about how he got to be the one to bring Jams’ story to the screen, why shooting on film was so important and how rolling with the punches not only became a theme of the film but extended into its release.

That basement that you see in the film is one that I have spent many years of my life in playing drums. [laughs] I don’t play with Jesse Jams and the Flams, but alongside my filmmaking, I’ve been a rock musician in Edmonton for many years, and Jesse and I have a couple of friends in common, one of whom is Lyle [Bell] who you see in the film in the band with Jesse, and another is Penny Frazier, who is Jesse’s personal advocate and an executive producer of the film. When I got approached by Telus Optik Local, a broadcaster in Western Canada, they were looking for short form, high-impact documentaries with a focus on youth and health and they wondered if I had anything that fit the bill. I said, “Wow, you should meet Jesse.”

The film stays entirely in Jesse’s perspective. Was it tempting to include anyone else?

I knew that would be a mistake. Traditional documentary form would have us talking to experts, but there is no better expert on Jesse’s life than Jesse, so I knew I wanted to avoid clinical or journalistic strategies and create basically a little rock doc where we embed with Jesse and walk beside him and learn his story directly from him. I also knew that we wanted to discover Jesse’s story as much through the songs as much as him talking to us because the songs are about his life. Like he says in the film, the songs are catchy and they’re funny, but they’re about real things, so we could really embed the songs not just as decoration after the fact, but we’d want to hear and see [the band] rehearsing a song and soundchecking, performing at a concert and then especially coming out of like when Jesse’s telling us about living in care, he’s got that great song, the riff on the Village People’s “YMCA,” but “It’s Not Fun to Stay at the YMCA.” If you listen to the lyrics of that, it’s really descriptive of the literal shitshow that was living at the YMCA and living in care.

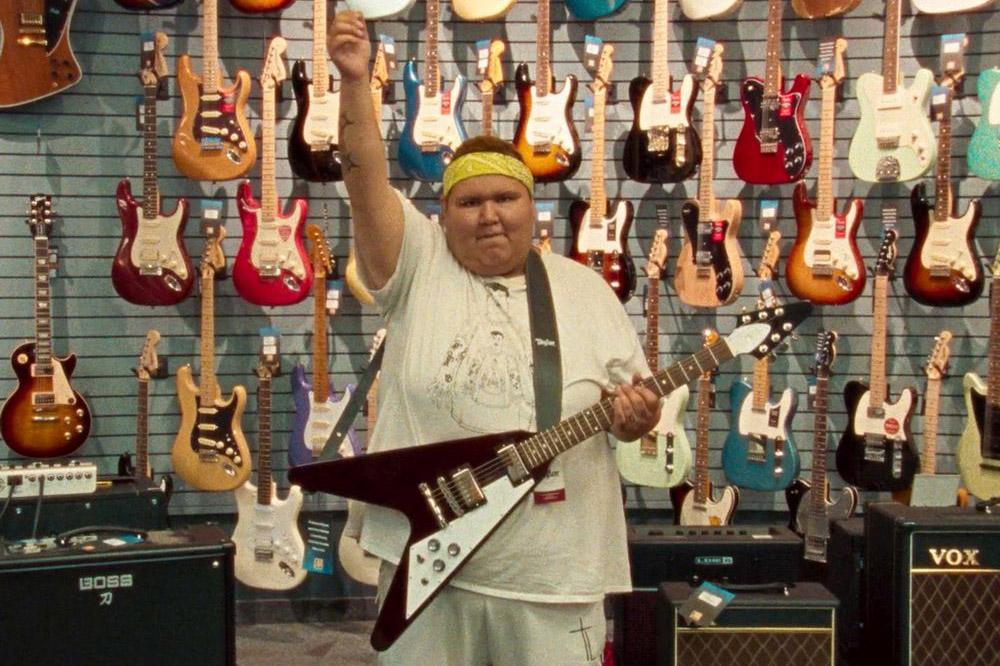

There are a couple scenes set at stores where he can really illustrate his condition using the scenery. How did those come about?

We followed Jesse on the week leading up to a big concert, and Jesse’s been in care for so long that when he speaks about his story, he will list eight complex disorders that he’s been diagnosed with or he will talk about the 45 placements he’s had since entering care and I knew it needed another layer so that didn’t just come across as clinical. So we went with Jesse while he shopped for a guitar and he went to get a pair of shoes that he could wear on stage, and finding an opportunity to combine his list of mental health diagnoses with different guitars in the store and then mirroring that with connecting the places he’s lived with the shoes — especially in front of a wall of backpacks because all kids in care get moved around so much that becomes the home that travels with you — it brought us good visual metaphors. That’s when I knew we had a movie and not just like a PSA.

Yeah, an extension of not wanting the film to feel clinical was that I wanted it to feel like a rock doc or an art film [because] if you look back at the history of the really excellent rock docs, the greats are shot on film so I thought well, if I wanted it to feel like it’s shot on film, certainly the easiest way to do that is to shoot it on film. [laughs] My cinematographer Mike McLaughlin and I decided to shoot on color Super 16 and then also we interjected all of these black-and-white 35mm stills because [Jesse’s bandmate] Lyle is always compulsively taking photos on his 35mm film camera. One thing that’s so beautiful about Super 16mm film is it has that soft focus and it comes in and out of focus, and of course, 35mm film is in very sharp focus, so I thought how nice to punctuate [the footage] in a percussive way with these stills, but then these stills would also be in black-and-white instead of color. Once we found that language, we really found the syntax of the film. Film makes it more emotional. If it were on video, it would feel more intellectual, and it would feel more in the head instead of coming more from the heart.

This has already been online for a bit. What’s it been like getting it out into the world?

It was a disappointment that it couldn’t have the international film festival run that it was poised to have. It was just getting started when the pandemic happened and rather than just let the film wait for the end of the pandemic, we had a sense the best way to reach the most people would be to put it online. At the end, that’s great because I feel like more people are seeing it and more people are seeing it who wouldn’t be able to attend the international festival certainly. And Jesse wouldn’t have been able to travel with the film, so this way, he knows that his friends and his peers are seeing it and he can watch the view count going up on Vimeo and people are reaching out and telling him how much they love the film and his music and the story, so in the end, it’s great that it’s online.

“Jesse Jams” is available to watch here and the soundtrack for the film is available here.