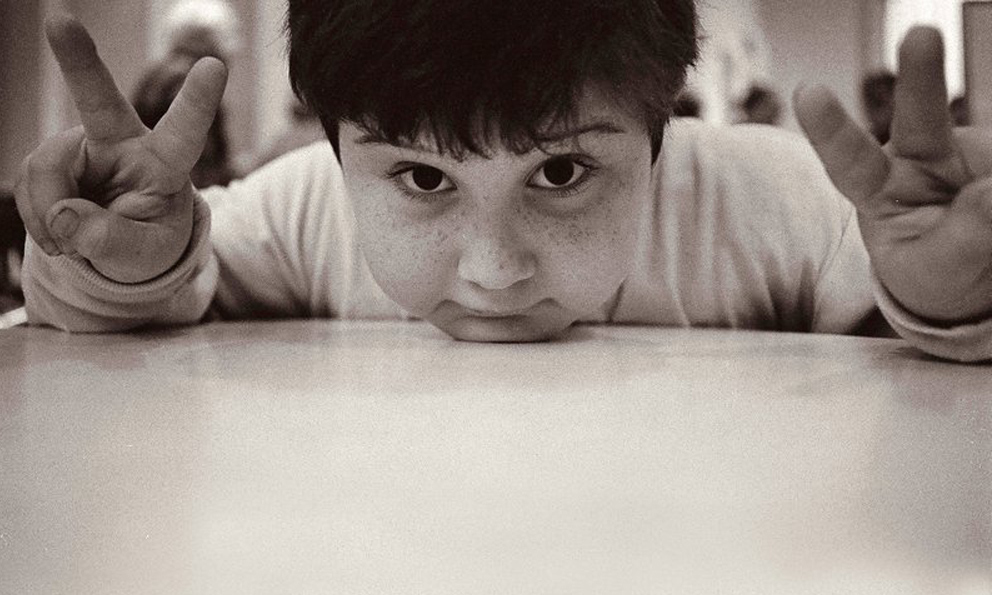

Sasha Joseph Neulinger’s mother Jacqui can remember being startled by her son’s prescience from an early age in “Rewind,” recalling a moment not long after he could start speaking when he told her, “I had to wait a long time for you because you weren’t ready [to be a mother].” By this point in Neulinger’s arresting chronicle of his stolen youth, you know that his sense of perception has been shaken, though in his childhood home videos he appears far older than his years, haunted and angry when he should be innocent and carefree, and the fact he sought to document himself using his father Henry’s video camera speaks volumes about being aware his predicament was amiss, even if he was too young to know exactly know what was wrong about it.

When “Rewind” begins, Neulinger tells the audience there are “pieces missing” from his memory that he’s trying to reclaim as you see him as an distraught child, yet remarkably he has access to nearly all of them after getting his father Henry, a videographer by trade, to open up his massive archive of footage and asks his therapist to look through his old case file with drawings that suggest what he was going through and things he said at the time that make far more sense now than they did at the time. The result is an extraordinarily captivating, if devastating, exploration of sexual abuse, both processing it and having to relive it again and again if the perpetrator is brought up on charges, as was the case with Neulinger, whose mother was told by the doctor who first saw her son that pursuing an investigation was “a door she wouldn’t want to open.”

While the film will likely require a trigger warning for survivors of sexual abuse, “Rewind” doesn’t need to be graphic about the crimes committed since one can simply look at Neulinger’s demeanor change over the many years he was filming himself or his father was to know what happened. The film is impeccably edited by Avela Grenier, offering up the same feeling of revelation that the filmmaker clearly experiences as he begins to interview the various members of his family and law enforcement that were involved in the case while introducing hints to just how horrific and pervasive the crimes that were committed against him were.

Within the larger framework of Neulinger beginning to grasp how he was failed, incurring the trauma of recounting time and again to all the parties necessary to take a case to trial from police to lawyers, the film impressively gives the room to everyone appearing onscreen to explain how exactly they were working with insufficient vocabulary to form a proper conclusion when based on the testimony of a child unable to fully comprehend what happened to him or was scared to say what he knew, as well as how their own experiences shaped the way they took in that information.

Somehow in documenting the family’s unraveling, Neulinger comes to show the strength that certain members were able to give to another, if not necessarily at the time, and although you know some connections were irrevocably broken, it’s extraordinarily moving how the director mends some for himself within the fabric of the film. When most of “Rewind” plays out like a horror film, you can understand why Neulinger would be at odds with his father’s belief that you’d only turn on the camera to capture the good times – both why Henry was drawn to his occupation and how there’s copious amount of home videos – but there is tremendous power in seeing the filmmaker taking the bad to make some good out of it, capturing the best and worst that humans are capable of in one brave and truly exceptional film.

“Rewind” will be released on VOD on May 8th and air on Independent Lens on PBS on May 11th.