As Karim Amer and Jehane Noujaim struggled with how to tell a story the imperceptible but profound human stakes of living in an increasingly digital world in “The Great Hack,” there was the uncomfortable realization that they were remarkably well-equipped to understand how their central subject Cambridge Analytica could help Donald Trump pull off such an unexpected win in the 2016 U.S. presidential election.

“As documentarians, we’re basically collecting data in the same way these tech platforms are – we get all their personal information and know everything about them to try and tell a story…no, I’m kidding, but there’s a truth in that,” Amer laughs now, just one irony among many in making the documentary which sees the duo behind “The Square,” which documented the triumph of Twitter and other social media platforms contributing to the overthrow of Egyptian dictator Hosni Mubarak, come to illustrate how those networks have been used to curtail democracy in “The Great Hack.”

Of course, Amer and Noujaim are far more responsible with their considerable powers and it is just one way they introduce humanity into a story that would seem unfathomable otherwise as the world’s largest tech platforms grapple with what ethics to apply to the copious amounts of personal data they’re capable of collecting. A subject Noujaim has been following since the start of the century with films such as “Startup.com” (with Chris Hegedus) and “Control Room” where the new opportunities to disseminate information has come with the challenges of setting boundaries in uncharted territory, the director and Amer, her partner from “The Square,” were initially intrigued with the geopolitical effects of the Sony Hack where private e-mails were weaponized as retaliation for the release of the film studio’s Seth Rogen comedy “The Interview,” but that trail led to looking into a far less public data mining operation with far more reach in Cambridge Analytica, who were harvesting information through seemingly innocuous social media polls that indicated personality traits and data culled from Facebook profiles to target potential voters with campaign messaging.

There are many revelations in “The Great Hack,” chief among them the relatively small amount of “persuadables” in key areas necessary to sway an election, making Cambridge Analytica’s efforts far less exhaustive than one would suspect, but in locating whistleblowers such as Christopher Wylie and Brittany Kaiser before they went public, Noujaim and Amer achieve something extraordinary from a filmmaking perspective, following Kaiser in real time as she re-emerges from seclusion on the beaches of Thailand to testify in front of congressional committees on both sides of the Atlantic about her role at Cambridge Analytica as the right-hand woman to disgraced CEO Alexander Nix. Her participation allows for the urgent verite-style filmmaking that Noujaim and Amer have become known for while telling a story that exists largely in 1s and 0s while putting a face on the deeply divided times we live in, both when it comes to technology and politics as Kaiser, a one-time volunteer for Obama’s social media team found well-paying work serving the Trump campaign as part of Cambridge Analytica. She is joined in the film by Carole Cadwalladr, the dogged journalist who first started tracking Cambridge Analytica for The Guardian after their role in the Brexit campaign, and David Carroll, an associate professor at Parsons and expert in dark data who searches for how deep the rabbit hole goes when it comes to what personal info tech companies are collecting, to form as comprehensive a portrait of this particular and precarious moment in time as possible.

In fact “The Great Hack” marks the second time (after “The Square) when Noujaim and Amer had to radically recut their film after premiering to acclaim at Sundance to keep up with the times and during a recent visit to Los Angeles on the eve of the film’s debut on Netflix, they spoke about rising to the challenge of the present while putting together something definitive, as well as getting immersed in the digital world themselves as storytellers in order to find innovative ways to make the gripping and provocative film.

Karim Amer: When we finished “The Square,” one of the themes in that film was the way in which technology was having a catalyzing effect on people embracing or attempting to claim the democratic process in their own way to write a social contract or to reimagine what it could look like. And it was amazing to come back to the United States and see all these technology companies – Google, Facebook, Twitter, being like “Arab Spring, look at what we could do. Our platforms foster democracy.” It was incredible. But then, the pendulum swung the other way. The same platforms were being used to track people. Dissidents’ information was available and we saw platforms of tech utopia engineered here in California being used to really stifle democracy and then actually begin to be agents of fascist governments. And no one wanted to take credit for that [or] for radicalization online — a lot of people joined ISIS.

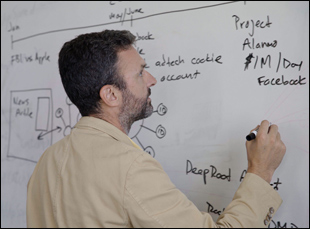

So that got our attention and got us to begin looking at what are the wreckage sites of technology and society. At first, we were interested in physical hacks, but [then] the Sony hack [happened] where you have the entertainment industry, politics and international affairs all happening at the same time [where] there was actually information warfare and reputational damage. The sophistication of that was actually even more remarkable than the physical attack, so that’s where our focus began and as we started looking for the stakes in this conversation, we found that the information warfare that was conducted on Brexit and the Trump campaign was quite remarkable. When we found out that Cambridge Analytica had 5000 data points to every voter in America, I was like, “What the fuck does that mean?” You should’ve known that was a reality, given that we’re even in this [Netflix] building, which collects data and uses it for purposes. But that was quite a shift for us and that began the journey into Cambridge.

Still, it was very challenging to make a movie about it. It’s a great thing to write about, but especially coming from a cinema verite school of filmmaking, we were looking for, “Who are the people on the journey you could latch onto and find?” So when we met Carole Cadwallr and then David Carroll, Chris Wylie, and Brittany Kaiser, they provided us corridors into this world. They were like passing ships because each of them was trying to come into this, but from a different angle and for a different purpose. You had outsiders coming in from David Carroll and Carole Cadwalladr’s journeys and then you had an insider in Brittany Kaiser coming out and we found that in that arrangement, you could structure a film.

Jehane Noujaim: This is the case in all of our films [where] you’re telling this verite story, but in the context of a world that is impossible to see. It’s invisible and there’s a deficit of language to talk about the issues, but in the end, this is a film, so it has to be told with an image. I ended up taking out so many of the tweets near the end of the film because it was like we’re not there in the theater or watching it on Netflix to read a book. We’re there to be entertained and to watch a movie, so what is the visual language that we’re going to use to tell a story that really hasn’t been expressed either visually or with language? We felt by partnering with the animation company that we partnered with to be able to tell the story of data was really the answer as to how to tell this story.

Karim Amer: And we wanted to bring to life a few elements of this. The first phase was to use the tweets over the normal cinematography, to layer it in this way so you feel like it’s constantly enveloping the people and creating this whirling [sensation]. Then we created this sound design to really bring that to life, to show the effect of the clicking and how this texture is around us all the time. Once we accomplished that, we still realized there’s a layer that we’re not showing and that’s where we went into the animation space [where] the objective was how do we show the POV of the algorithm [because] we needed to show the viewer how the algorithm sees the viewer. We never used animation in a documentary, though we produced “The Breadwinner,” so it was a learning experience, and it was really incredible to work with Shy Kids and Alt-C to really bring it to life.

You see that really in the first 10 minutes of the film as David goes into what we call the data wormhole. Our inspiration for that actually was “Fantasia,” and we told the animators to create like a fantasia of the data dust and exhaust that we have. With the help of Judy Korin, our amazing producer who’s also brilliant in visual aesthetics, and Pedro Kos, a producer and writer on the film, we were able to really bring this to life in a great way. Then on the soundstage, we spent more time than we ever have on any film on sound design because it was really important to create the soundscapes of what the data world looks and feels like. Our amazing composer Gil [Talmi] was inspired to compose a really original score from elements of data and technology from this mandate, and like Jehane was saying, there’s a deficit of language, so how do you get people to care if they can’t see what’s happening? It was really difficult, and I think we did a good job at really figuring out a cinema language for this world, which I hope is just the beginning because this world is not going away any time soon. [laughs] And I’m excited to see how other filmmakers are going to enter this space and try and make it theirs and show different elements of it.

Karim Amer: I didn’t know we’d be going to the Mueller investigation together. [laughs] That was pretty interesting. I didn’t know she had met with Julian Assange and had interactions with him as he was one of the most sought-after people on the planet. But what I did know was that here was a person that began as an idealistic Obama intern who had believed so much in what she was doing and had witnessed the power of this technology as a very powerful political tool in the messages of hope and “Yes, we can” and then ended up in a very different place, pitching the Trump campaign [working for Cambridge Analytica], being Alexander Nix’s number two in the company and finding herself being really good [at the job] in a world that had become much more mercenary around data and elections. So she had all of the elements that we look for in a character – somebody who’s charismatic, who’s on a journey and who’s about to jump off a cliff that’s interesting. I just didn’t realize how much of a rollercoaster it would be.

[Brittany’s] seen the film and gave the best compliment, which is that she felt the film was honest and respectful and truthful portrait of what happened. That’s the best you can ask for as a documentary filmmaker and I think that her story of redemption is very important and quite appealing to me personally because we’re in a scary place as a country and as a world at large when we’re so polarized and now we’ve realized our polarization is actually being incentivized by tech platforms, [so you wonder] how do we get out of this state? Either you end up in a civil war or you find ways for redemption and I think redemption is something we don’t really get an honest look at sometimes. We have a romantic view of how change happens like we saw in “The Square” and romantic view of who whistleblowers are. You don’t become a whistleblower when you’re working at a nonprofit. You have to be in a complicated situation to blow the whistle to begin with, so my question is for those who want to judge Brittany is asking how many Brittany Kaisers are there out there in Silicon Valley right now, working at companies where they’ve seen things that aren’t necessarily illegal because our legal systems haven’t caught up with the reality we live in, but things that are certainly questionable to the values we like to think we subscribe to? And we should ask ourselves what values we subscribe to and how do we stand for them in the digital era.You alluded to it earlier, but after making “The Square,” does it actually feel like an obligation as much as an extension of your work to make a film that comes to question the uses of technology that was previously celebrated as a tool of liberation?

Karim Amer: It’s interesting because when you’re making a film, you’re so in it, you don’t see what it is and the overwhelming response to the film, which has been very positive is people are really scared. It [feels] alarmist in a way, which is not usually my tone or Jehane’s tone, but I think the alarm is not because of the film. The alarm is because once you have the awareness of seeing the interconnectedness of how data works and how it’s affecting us, you can’t really go back. It’s like once you realize what global warming is – once you see it, you’re like “Oh, that’s what’s happening to the planet,” that’s what’s happening to human autonomy. And what was parallel to “The Square” with this was that right as we took “The Square” to Sundance, the story changed and continued to develop and we continued filming and we edited the movie completely differently. The same thing happened here where right as we were getting to Sundance, we got access to a whole new aspect of it and continued filming after Sundance…

Jehane Noujaim: It’s the casualties of war, making a current films about the zeitgeist. [laughs]

Karim Amer: I think Sundance is forever mad at us, but it’s what we have to do because at the end of the day, we’re making these films to try to tell them in the best way possible.

Jehane Noujaim: Every time we’ve decided to go to Sundance, we felt like we’ve finished the film in time, but in the case of “The Square”, [Mohamed] Morsi was in power and proceeded to do the same kind of dictatorial moves that Mubarak had done [that led people to revolt] and all of our characters were back on the streets protesting, so it just wasn’t the end of the story and after our characters opened up their lives to us, if we hadn’t told that story to its completion, that would’ve been horrible for them. In this case, we literally got increased access inside to Cambridge Analytica to the Chief Operating Officer (Julien Newland?), and [also] these recordings that had never been heard before, which really brought to life how data was being used.

Karim Amer: And about the intent, right? One thing people forget in the Cambridge Analytica story sometimes is one of their expertises was voter suppression, so we need to ask ourselves if voter suppression is normalized now in the American political system?

Jehane Noujaim: It existed in Egypt.

Karim Amer: But also in through the history of the United States, whether it’s through gerrymandering… [or other means] and weaponizing voter suppression in the digital era is a whole other level where you can actually know so much about someone and target them with information that allows them to really deflate their interest to be part of the democratic process, and the fact that we have no guardrails up against that and legislation up against that and even worse that it feels like a lot of technology companies have no problem profiting off of that, advertently or inadvertently – that’s worrisome to me.

We come from Egypt. We’ve seen that democracy is not something you take for granted. It’s not a God-given right. It doesn’t grow on trees. You have to fight for it and you have to take care of it. And Silicon Valley is standing on the shoulders of open society — there is no Silicon Valley without the open society and its ideas, building a refuge to bring all these engineers from around the world to imagine the future – so to say that the casualties of that don’t have a place on their balance sheets, which is ultimately what they’re saying in their position that they’re taking no responsibility whatsoever, is actually quite sad. That’s why you see this shift in mood towards technology companies with populations around the planet being like is this what we signed up for?

We called it “The Great Hack” because it was about people’s minds being hacked, being shaped and that’s what we wanted to bring awareness to because our only agenda with this film is a cry out to people to think for themselves and to not be okay living in a world where algorithms that are amoral are continuing to shape our decision making because the one thing that separates us from the algorithm is morality and if we lose our autonomy in that space, I’m not sure what’s left of humanity.

“The Great Hack” is now streaming on Netflix. It opens theatrically on July 24th in Los Angeles at the Monica Film Center and New York at the IFC Center.