Like many people who arrived as soon as the doors opened to the Egyptian Theatre in Los Angeles on December 12th for a screening of “Interstellar” accompanied by a post-screening Q & A after with director Christopher Nolan, the evening’s moderator Guillermo Del Toro was hardly fazed by having to settle in for what would be close to six hours, given the film’s 165-minute running time.

“It went so fast, my assmeter was at zero,” exclaimed Del Toro after the screening. “I wasn’t squirming.”

However, he did shed a tear or two, admitting to Nolan after the screening “Interstellar” was the first of his films that made him choke up. It may have been late at night, but the “Pacific Rim” director was just getting started.

“It’s a movie you could actually watch continually, preferably with some altering substances,” said Del Toro, who didn’t miss an opportunity to flatter the director, but also was the perfect inquisitor to dig into the inspirations of the time-bending space adventure which sees Matthew McConaughey lead a crew into the furthest reaches of the galaxy to find a hospitable new home planet when the earth is in decay. Describing the film as a Möbius strip that’s “profoundly symphonic,” Del Toro wondered aloud how Nolan could bring such disparate elements together into a cohesive whole, where as he put it, “dialogue becomes another rhythm of music, where it becomes important as emotional code” and “you rhythmically use repetition in certain angles — the repetition of the camera on the side of the ship [for instance] — over and over again to punctuate.”

“There is also this love for adventure films and an era of loftier ideas,” added Del Toro. “I see the movie and I feel the evocation of Shackleton, [and] of strangely and horribly for me, ‘At the Mountains of Madness’ of HP Lovecraft…”

“Yeah, sorry about that…,” Nolan smiled, knowing Del Toro was referring to his painful attempts to get his dream project off the ground. Yet Nolan was more than happy to oblige when it came to speaking about the influences on the film, acknowledging how ideas will often build upon each other as the process of making one of his films plays out. At first, that brought to mind his initial discussions with composer Hans Zimmer that began with the use of a pipe organ as the baseline for “Interstellar”‘s score, talking about ideas of religiosity and though Nolan insisted, “It’s not a religious movie, aesthetically speaking, the architecture of cathedrals – the stained glass windows, the sound of the organ, these represent man’s most successful attempts to communicate the metaphysical, what might be beyond our reality.”

Throughout the evening, these were the other insights Nolan gave for the production:

On the structure: Said Nolan, “There’s a very strong relationship between the structure of the film and some of those [M.C.] Escher prints of Möbius strips, particularly the [one of the] horsemen coming up and meeting each other. There’s a story structure that’s deliberately using those things as a jumping off point, but then aesthetically, the repetition of camera angles came about really because this had to be a science fiction film I could believe in the physics of it… So we looked at all this NASA footage. Of course, what you realize is with real space footage [is] you’re always seeing the same angles because they have the camera mount, the hard mount [on the spacecraft]. Once you embrace that as an idea, interesting editorial, aesthetic, and symbolic things come out of that.”

On the structure: Said Nolan, “There’s a very strong relationship between the structure of the film and some of those [M.C.] Escher prints of Möbius strips, particularly the [one of the] horsemen coming up and meeting each other. There’s a story structure that’s deliberately using those things as a jumping off point, but then aesthetically, the repetition of camera angles came about really because this had to be a science fiction film I could believe in the physics of it… So we looked at all this NASA footage. Of course, what you realize is with real space footage [is] you’re always seeing the same angles because they have the camera mount, the hard mount [on the spacecraft]. Once you embrace that as an idea, interesting editorial, aesthetic, and symbolic things come out of that.”

On the look: Nolan credited cinematographer Hoyte Van Hoytema, the director of photography behind “Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy” and “Her,” for going against the grain with what Del Toro described as the “worn down, not sterile, but grimy” look of space travel. (Del Toro loved Nolan’s curt, prim pronunciation of Van Hoytema’s name so much he made him say it twice.) He said he struck up an almost instant rapport with the cinematographer after his longtime lenser Wally Pfister decided to direct, and actually appreciated the fact that Van Hoytema had never done anything on the scale of “Interstellar” before, which Nolan laughed, “was great fun for me because he would get worried about how we’re going to do this and I was like, ‘ehhh, don’t worry.'”

But Nolan added, “Quite seriously, what he brought to it was [my] being able to say, [you don’t have to worry about the scale of the thing. You bring your eye to it, the freshness of your vision. He’s very into greasy closeup and things like that and I really loved the patina of that. We were looking at a lot of [Andrei] Tarkovsky films like “The Mirror,” where he uses elements — fire and wind and all those — so with everything we had to deal with [in “Interstellar”] like the dust storm and what life on earth is like, how do you not glamorize that, but make it beautiful somehow in its natural state? That’s what we started with with the farmhouse. Once you’ve cracked that, then you have the huge challenge of how do you apply that to fantastical elements?”

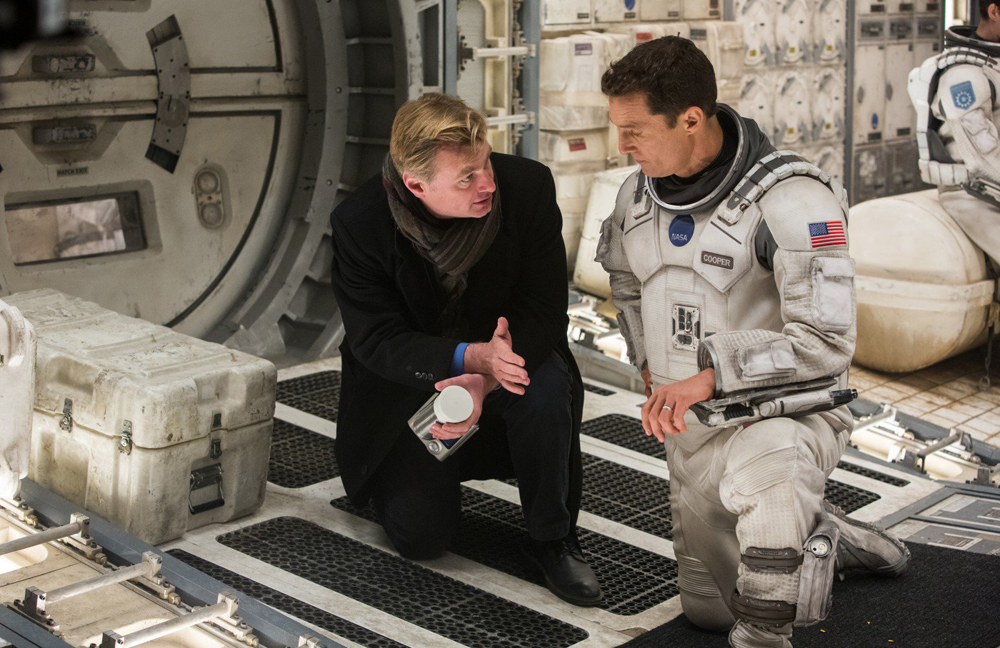

The solution Nolan came up with, along with Van Hoytema and production designer Nathan Crowley, was loosely inspired by Philip Kaufman’s “The Right Stuff,” which he famously screened for the crew before filming started, but had it in mind long beforehand for the way it was shot using practical visual effects such as rear projection. Said Nolan, “It was a lot about going to visual effects guys and saying we don’t want to use green screens. We want to put real views outside the spaceships. We want to build the spaceships fully enclosed so they’re really like locations, fully enclosed, not like sets… Once we were there [on location] and able to jam the IMAX camera behind the console of the ship and just grab shots as we went. When [the crew] comes to the water planet, we’d run that entire sequence every take because we would have all the lighting cues and the movement of the ship, so it almost was like a simulator more than a set [for the actors] and that way, Hoyte could just grab shots. I could find different angles and pieces of things and build up a library of footage more like a documentary. That really helped with finding reality to it and finding beauty in it without fetishizing it.”

The solution Nolan came up with, along with Van Hoytema and production designer Nathan Crowley, was loosely inspired by Philip Kaufman’s “The Right Stuff,” which he famously screened for the crew before filming started, but had it in mind long beforehand for the way it was shot using practical visual effects such as rear projection. Said Nolan, “It was a lot about going to visual effects guys and saying we don’t want to use green screens. We want to put real views outside the spaceships. We want to build the spaceships fully enclosed so they’re really like locations, fully enclosed, not like sets… Once we were there [on location] and able to jam the IMAX camera behind the console of the ship and just grab shots as we went. When [the crew] comes to the water planet, we’d run that entire sequence every take because we would have all the lighting cues and the movement of the ship, so it almost was like a simulator more than a set [for the actors] and that way, Hoyte could just grab shots. I could find different angles and pieces of things and build up a library of footage more like a documentary. That really helped with finding reality to it and finding beauty in it without fetishizing it.”

On the design of TARS, the utilitarian robot that helps the crew: Like “The Right Stuff,” “2001: A Space Odyssey” has often been cited as a reference for “Interstellar” and while Nolan hasn’t disputed it, it wasn’t necessarily for the reason you might think. When Del Toro spoke about the unusual design of TARS, thinking only Donald Cammell’s “Demon Seed” had posited such a non-anthropomorphic robot onscreen, Nolan said the inspiration actually came from watching “2001” with his young children and as he describes, “One of the questions they asked me was, ‘Why does the computer talk?’ And I realized to their generation, the idea a computer is a consciousness or an entity that could speak to you is absurd because a computer is just a tool for them [so] the idea of a talking computer doesn’t make any sense.”

That led Nolan to decided against creating “a traditional movie robot.” Instead, he said, “I wanted to do something that I refer to as an articulated machine and I wouldn’t talk about them as robots. I would say it should be a piece of equipment like a dolly or a light stand, something like a big hinge – it’s a machine. And when Nathan [Crowley, the production designer] and I looked at forms, we said if you’re going to go that way, then go with the absolute simplest block of metal with these fractal-like subdivisions that you may find in electromagnets. We tried to make it beautiful in a way that made it feel like it wasn’t trying too hard to be friendly because what we found is the human brain is incredible at assigning human characteristics, so we went with as little of a face as possible, but you soon start to see the screens as eyes.”

That led Nolan to decided against creating “a traditional movie robot.” Instead, he said, “I wanted to do something that I refer to as an articulated machine and I wouldn’t talk about them as robots. I would say it should be a piece of equipment like a dolly or a light stand, something like a big hinge – it’s a machine. And when Nathan [Crowley, the production designer] and I looked at forms, we said if you’re going to go that way, then go with the absolute simplest block of metal with these fractal-like subdivisions that you may find in electromagnets. We tried to make it beautiful in a way that made it feel like it wasn’t trying too hard to be friendly because what we found is the human brain is incredible at assigning human characteristics, so we went with as little of a face as possible, but you soon start to see the screens as eyes.”

Nolan went on to talk about how he further made TARS a real part of the crew by casting the multi-talented actor Bill Irwin to be the puppeteer behind it, saying, “He’s a wonderful actor, but also a clown and a performer who can take a chair and dance with it, give it some life.” He continued, “I brought him in with the special effects guys and said, ‘You’re going to do this robot, but you’re not going to come to the voiceover booth six months after we finish shooting. You’re going to puppeteer the thing on set and you’re going to be there to act with the rest of the cast. He took on that challenge with the special effects guys who designed this 200-pound rig [for TARS], and even when they’re out in the water in Iceland, he’s puppeteering this thing, so he was always there to be able to develop the character the way an actor would on set with other people and the computer graphics guys would take over at the point of removing him from the shots.”

On the influence of the bulky IMAX camera: Del Toro asked Nolan in indelicate terms, how he “doesn’t shoot his wad” while building up the multi-stranded, action-packed climaxes he’s known for and Nolan spoke about his use of cross-cutting between storylines, saying that jumping across different aspects of the plot “allows me to control the pace of the climax, of what I call the snowballing effect of the action, so you can set a couple of things in motion, then as they start to come together, you can go a little further or a little faster or more extreme than hopefully what the audience is expecting. In that way, you can do enormous things early on that would be hard to compete with head to head [later], but you have a structural acceleration to the last act that allows you more and more extremity to that action. Then you can jump into a black hole, but you better come up with something.”

But Nolan also allowed that the answer may be as simple as the kind of camera he uses. “One of the things I really enjoy about using the IMAX camera is it imposes a discipline. It’s big and heavy and the frame is huge. It sees everything. It forces you into a simpler form of filmmaking in terms of mise-en-scène. It makes you really think about each image in a way that as a modern filmmaker, I tend to skip over. The film has plenty of cuts, but using that camera slows you down a bit and makes you think a little bit more about each of those things and how they relate to narrative. In looking for a symbolic narrative in which you have to choose between these planets and one is water and one is desert and one is ice, everything is intended to feel resonant and simple in a way, so the action therefore has to accompany that.”

On the film’s sense of adventure and Dr. Mann: When Del Toro brought up the film’s sense of adventure, Nolan further addressed the need to keep things simple, delving into the screenwriting process with his brother Jonathan. Although originally scripted for Steven Spielberg to direct, Nolan kept tabs on the project as it made its way through development and knew what he wanted to change when he came onboard to direct.

On the film’s sense of adventure and Dr. Mann: When Del Toro brought up the film’s sense of adventure, Nolan further addressed the need to keep things simple, delving into the screenwriting process with his brother Jonathan. Although originally scripted for Steven Spielberg to direct, Nolan kept tabs on the project as it made its way through development and knew what he wanted to change when he came onboard to direct.

“When I took over the screenplay, what I said to my brother is I loved the characters he created and the first act, but I needed a second act that as I called it was symbolic or very stripped down,” recalled Nolan. “‘Treasure of the Sierra Madre’ is a great model in my mind to say if you’re taking this small group of people — and [in this case] you’re taking them away from the earth — into this most extreme environment possible, you’re clearly going to have to explore what that does to their nature. The other big point of reference was [Erich] von Stroheim’s ‘Greed’ with the two guys wrestling, it’s this slightly ridiculous idea of the fate of everything coming down to a fist fight in an awkward space. That was really the essence of saying if you take these people out to the most private space imaginable, you uncover the most raw version of human nature.”

That led Nolan to discuss the enigmatic Dr. Mann, who helmed the one (seemingly) successful NASA mission to colonize another planet that becomes the thrust of the film’s second act as the crew searches for him. Spoilers ahead if you haven’t seen the film, but after keeping the actor playing him a secret right up until the film’s release, Nolan praised Matt Damon for what he did with the role. “What I loved about what Matt did with that opportunity is here’s a man who is a crazy person, he plays him as a coward, a banal, ordinary coward who’s just chickened out, frankly and has just rationalized his own cowardice into a philosophical justification that everybody’s doomed and that to me speaks to the spirit of adventure. There’s some [Joseph] Conrad in there. There was talk about Dr. Mann as remarkable in the way Kurtz is talked about as remarkable in “Heart of Darkness.” It’s definitely meant to be that idea of the tale of journey or exploration and what that might uncover about human nature.”

Comments 1