If Ursula Macfarlane was taken aback by the material that was presented to her by the UK production company Raw TV, the outfit that has made a name for themselves by pursuing stories that seem too good to be true for such films as “Three Identical Strangers” and “American Animals,” you can imagine how Paul Fronczak felt when he opened up a box in the basement of his house suggesting that he had been kidnapped as a baby. Living comfortably in Chicago until the age of 10, Fronczak was surprised when he saw the newspapers his parents kept around from years earlier, telling the story of a child that had been left on the streets of Newark and returned to a couple that had their baby taken from them shortly after birth, never to be seen again until police in both precincts put two and two together.

Yet the math never entirely added up for Paul, whose mother Dora confirmed the story to him, only to add that she wouldn’t speak about it again, and after the birth of his own child, he began to look into his own family tree, wondering if anything would come out of the woodwork. Although he went to the local media hoping the attention might draw out further clues about the case and ultimately write a memoir about his experience “The Foundling” with co-writer Alex Tresniowski, the whole truth wouldn’t come out until Macfarlane’s “The Lost Sons,” which builds on the detective work Fronczak did with an investigation of its own, charting a 50-year emotional rollercoaster that everyone involved can’t seem to shake the details of yet each only hold a few specifics that leave the larger mystery alive and well.

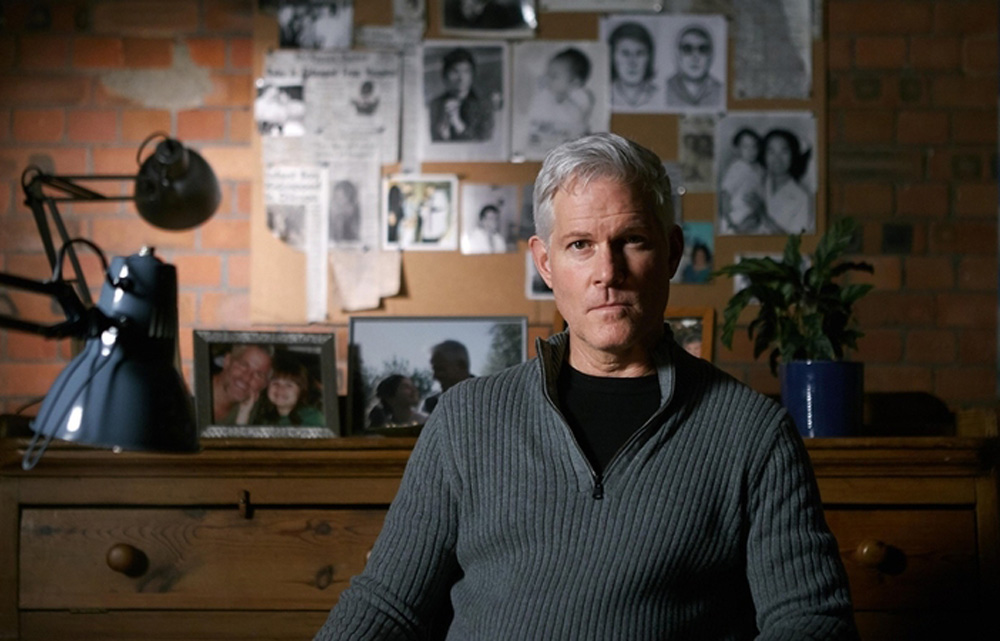

Amidst its wild revelations, Macfarlane, who last tackled the fallout from the Harvey Weinstein scandal in “Untouchable,” never loses sight of what impact that sense of uncertainty has had on Fronczak, who picked up the nomadic life of a musician before ultimately settling in Las Vegas and whose dogged pursuit of the truth about his childhood threatens his potential to move forward. Just as memories of experiences Fronczak might not have even been present for dance around in his head based on what he’s been told, the film seamlessly blends recreations with present-day interviews to make it just as vivid and immersive for an audience with exactly the same awareness of where it’s going, which is to say none. (As Fronczak exclaims at one point, “I’ve watched a lot of movies and I’ve never seen one this fucked up,” to which you can only nod your head in agreement.)

With “The Lost Sons” premiering at SXSW this week, Macfarlane spoke about how one berserk experience led to another as she had to pause and eventually complete the film during the COVID-19 pandemic, yielding some unexpected benefits as far as the story was concerned, as well as finding ways in which Fronczak could express himself in ways only the cinema would allow.

How did you get interested in this crazy story?

Crazy is the word. I didn’t find the story, it came to me. I was working with Raw in the UK, and they’re not strangers to this kind of larger-than-life, stranger-than-fiction story. They had met Paul because they had found the story actually on a BBC News website because I think he’d come over to the UK to do some press around his memoir. They got in touch with him, and then they told me about the story and I just said, “Wow, that’s a filmmaker’s challenge like no other.” It’s such a incredible story [with] twists and turns. It’s harrowing, but also uplifting and it’s got so many ingredients that are about families and how we all navigate the trauma that happens to us through our lives. Plus it’s just an incredible mystery, which is always great to have the opportunity to do as a filmmaker.

When you’ve got the memoir, is that where you start as a foundation or do you start anew with your own investigation?

The book was very helpful because it’s a complicated story. There’s a lot of DNA going on in it, and I am not a scientist, so that’s all quite complicated and for someone to set that all out, investigate it and write it well into a really good compelling story [was helpful]. But in terms of finding subjects to speak to it, we had to do a lot of that work ourselves because since Paul had done the memoir, quite a few of the people had died or didn’t want to talk or life goes on. In terms of the Chicago side of the story, where everything begins when a baby gets stolen, we had to dig around to find the old detective and the nurse who was in the hospital and people that Paul had not actually met when he did his investigation, so that was fun for us and then there were people later in the film that I don’t want to go into [for fear of spoiling it]. But the book was an amazing roadmap, then in the last part of the film, we filmed in the present day as things unfold, so that was a journey that we went on together.

For this particular story, is it intimidating to go into this not having any idea how it was going to end?

Yes, it really was. It’s no secret to know that this is a film about Paul discovering that he’s maybe not who he thought he was, and then he has to go on this journey to find out who he is, and in so doing discovered things that were very difficult in some cases and also, has forged some great relationships with some incredible people that you see in the film. But it was very difficult, because the people involved with the last few scenes, we spent a long, long time trying to get them to trust us and to be okay with telling their story in the delicate way in which we had to do it. Funnily, I think COVID helped us, because we’d got to certain points in the edit and we didn’t have an ending, but we had to stop because we had to stop and we didn’t have more material. This was last March and we thought, “Yeah, by July, we’ll be back out filming again. And then back in the edit.” Of course, we had to wait and while we did that, we managed to nurture these relationships that ultimately led to us being able to film the ending.

This isn’t related to the ending, but it was interesting that when it’s a story that people might want to keep secret for whatever reasons they may have, you’re able to talk to relatives about it – it was passed down, even if it was never fully fleshed out. Was the fact that it was so vivid to people that were only indirectly involved intriguing to you?

You’re right to say that because sometimes when you make a film and it’s decades in the past, you think, you don’t want the story to be told by third-party people. You want it to be told by people who there. Often you end up having to interview historians or someone who’s written the book, but in this case, there are not many people left. There’s the detective, the nurse, the daughter of one of the detectives, but they remembered it so vividly because it was such a traumatic harrowing event, and they all had a role in it one way or the other. They never forgot it. Even if it was one of them [where] her dad was talking to her when he came home from work, [saying] “We’re working on this terrible case, a baby’s been stolen,” it’s everybody’s worst nightmare. Even her mom was crying because it was just so upsetting. So over the years, no one had made a film about it and nobody had talked to them about it, and we came away thinking, “Gosh, this really marked these people,” particularly the police because it was such a long investigation and they took a very, very long time to get it solved.

Was it difficult to create a unifying aesthetic? It was really impressive not only how the dramatic reenactments were incorporated into the film in dialogue with the archival material and the interviews, but that you seemed to create certain bridges with colors and camerawork.

You’ve [usually] got to really work the material whereas this material almost did the work for you because the story is there, so for us, it was about how do we tell it? Do we do flashbacks? We played around a little bit with time and reprising things and flashbacking as the story grows in its significance, and it took a long time to work it out. It wasn’t obvious straight away. And you had to really sit with the material, learn it, meet people, just figure out where do we hook the audience in? There’s a section of the film that has DNA and family trees, which is quite complicated, so [there was a question of] how do you simplify that without losing the subtlety of it? But it’s a wonderful challenge [when] twists and turns are the best thing about filmmaking.

When I found out that it took place in Chicago, and that Paul lives in Las Vegas and then there’s a whole East Coast side with Atlantic City, [which is] almost like a faded glory version of Las Vegas, I thought, “God, we’ve got these three incredible locations and they’re all very rich and they’ve got their own color.” Chicago’s the heavy, big buildings and it’s the Midwest, and then you’ve got Vegas, which is obviously crazy and full of neon and you’ve got the desert, which is all kind of reds and oranges. Then you’ve got Atlantic City, which is on the sea and [has] its own weird, slightly strange vibe to it, so it felt like a gift to be able to look at all of these landscapes and put Paul in the middle of them. Obviously he’s the connective thread that runs [through] and he’s a traveler, he’s a wanderer. He left home in the Midwest very young to go play in a band in the Southwest and he’s always roaming and it seemed appropriate that we could have these different landscapes. I also always wanted to film Paul running because he loves running, and I thought Las Vegas, what a great place to run, [with] all those lights.

That scene of Paul running across the Vegas Strip at night is one of the best in the film and you get a lot of mileage out of his workout routine, because there’s another revealing moment in a scene where he’s lifting weights. Did it seem like an obvious way to express his emotions?

The running just felt to me like a guy who was always chasing, and he can’t stop today because there’s still stuff that is unsolved. Particularly at the bit in the film that provokes the running scene, it just felt that I needed to express somehow the fact that he can’t stop and he will carry on. He’s very fit and he’s dedicated and determined — I don’t think he likes to stop running actually.

You mentioned that COVID actually helped as far as buying more time to get the interviews you needed, but was it tricky pulling together on the backend when you couldn’t be in the same room with your creative team?

It’s hard because I love being in the same room. It’s all about the creative energy and saying, “Hey, what do you think about that? Oh, let’s have a look at that transcript.” When you’re working with somebody remotely, what happens is you talk, they cut something, they send you a link, you watch it, you call them back. There isn’t the immediacy of that real time interaction. But thank God we can do that because otherwise production would have just ground to a halt. I don’t know what we’d have done.

When I got to the final stages of post-production — the sound mix and the color correcting grade, I was fortunately working with a production house in London where you do all the big feature docs and movies and they have a huge theater for doing the grading, so I was able to sit very socially distanced from the operator, and that was such a joy because I hadn’t had that experience for months and months. I just hope that we can get back to that way of working soon. But a lot of editors that I know have actually enjoyed working at home, because they’ve seen their families more, and I totally understand that, so in the future, it may be more of a mix. We’ll see. It certainly changed our ways of working.

What’s it like to get to the finish line?

I’m so happy. I’m so bummed that I can’t go because everyone I know has been just said [SXSW] is the most fun. I’ve been to Austin, Texas and had a fun time, but what a shame. They’ve done an amazing job like Sundance did, and I think we’re just going to have a different experience. And hopefully this time next year we’ll be back or maybe the year after. It’s just different.

Hopefully you can hear the gasps from wherever you are.

That’s the thing when you’re watching a film with an audience. It’s the best thing in the world. You [work on it] for months and months and months, hoping that it’s making people feel something and it’s such a joy when you’re in the room and you hear the no breath or the laughs or whatever, but maybe later on this year that’ll happen. Who knows?

“The Lost Sons” will screen at SXSW beginning on March 16th at 2 pm CST.