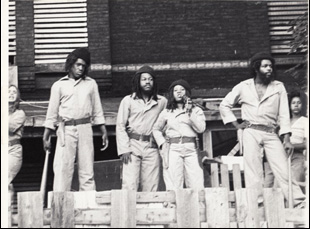

There was a reason that Tommy Oliver had never heard the definitive story of MOVE, even though he grew up in Philadelphia where the organization had formed in the 1970s and had been a staple of the news during his childhood in early 1980s. A collective of African-Americans with a desire to truly go back to their roots as caretakers of this earth with a strong belief in animal rights and widely available community housing, the group had been identified by the local police as a a violent threat with little justification besides the color of their skin. Sadly, that was enough for journalists in TV and newspapers at the time to offer up sensationalized coverage that trivialized their efforts and portrayed them as Police Chief Frank Rizzo wanted them to be seen, giving him the support to drive them out of their house in Powelton Village, culminating in a made-for-TV standoff in 1978 in which one police officer had been killed by a stray bullet, quite possibly by one of his fellow members of the force.

Yet the narrative that took hold in Philadelphia was that the nine members of MOVE were responsible, leading to convictions on third-degree murder that carried virtual life sentences and with only those in power around to recount this story and others distrustful, given how MOVE had been portrayed to the public in the past, Oliver was faced with an uphill climb for “40 Years a Prisoner,” a fascinating chronicle of an organization that had set out to make great social change and became an example of why such rethinking of society needed to take place. Thankfully, the filmmaker not only had the drive to turn over every stone he could, but the insight to bring the story to the screen in such an affecting way after connecting with Mike Africa Jr., the son of MOVE members Mike Africa Sr. and Debbie Sims Africa who had never seen his parents anywhere but behind bars after Debbie had given birth to him not long after she had been incarcerated.

Like Africa Jr., Oliver had also spent time as an adult piecing together his childhood for his harrowing feature debut “1982,” dramatizing his mother’s struggles with drug addiction as his father (Hill Harper, as a character invented for the film) attempted to keep the family afloat, and as Africa Jr. seeks to his parents’ parole and comes to discover who they really were when so much of their identity had been wrapped up in how they had been portrayed in the news. “40 Years a Prisoner” offers as much of a revelation to audiences, not only setting the record straight as far as MOVE is concerned, but resurfacing the shocking police actions against them, following their standoff in 1978 with a bombing in 1985.

After a year in which these issues have been brought to the forefront of American culture, “40 Years a Prisoner” shows a fight for justice that has been going on for decades and takes many forms, not the least of which is having filmmakers such as Oliver sticking around to counter a historical record that previously excluded the voices of minorities, and with the film’s premiere on HBO following a festival run that began earlier this fall at the Toronto Film Festival, he spoke about the depth of research it took to accurately reflect the story of MOVE and how he was able to create the special feeling of a proper premiere for those involved in the film even during a pandemic. (Additionally, audiences should know that Oliver filmed a special epilogue for HBO Max that would require spoilers to “40 Years a Prisoner” to describe, but will undoubtedly be worth checking out.)

I grew up in Philly and you hear about MOVE, but I never really understood who they were or what happened. You hear about them in sort of fractured narratives and whispers like, “There was this group and there was this bomb…” but I never understood what it meant. At some point, I went down a rabbit hole of research and I read every single article I could find. I went to the archive at Temple University where they have 72 boxes of content and I went through many of them and I realized there was still stuff missing, so I had a buddy Maxwell Brown, who works for the mayor and knows everybody, and asked him if he could make an intro to MOVE. He made an introduction to Ramona Africa and when I went to meet Ramona, she brought with her Mike Africa Jr. Mike and I hit it off immediately and I just learned so much in that meeting that changed things. One, I had no idea that his parents and the other MOVE members who were in prison – two of them had passed away at that point – were still in prison for what happened in ’78. I had no idea that he was literally born in prison. And then to learn that he had committed his entire life to getting them out, and on top of that, this is a guy who had gone through so much yet he did not have a single shed of bitterness about him, I just found to be incredible and beautiful.

[Mike Jr.] was just a guy who wanted his parents home. That’s all it came down to. And then on top of all of that, the realization, which was a hard one for me as well, that the things MOVE was fighting against some 40 years ago – police brutality, black incarceration, systemic racism, abuse of power – are the same things we’re fighting today. So that’s what set me on my path. Even though MOVE had been fairly cautious about the idea as anybody, being around the media and journalists because they had been burned so many times or misrepresented, Mike opened up in a big way and we went off on these parallel paths, following him as he was trying to get his parents out and then for me, to try to really understand what happened in ’78, which required a ridiculous amount of research because there were no definitive accounts of what happened in ’78.There’s a scene of Mike Jr. with his own extensive research. What was it like initially walking into that room like?

Mike was looking for anything that could help his parents out, so he had a giant collection of stuff, actually, for the most part, there were archives or files that were in the house that was in the house that was bombed on Osage Avenue and he wound up inheriting them basically, so he had those files and he had thousands upon thousands and thousands of documents. We digitized over 10,000 pages of court transcripts. We went through every single archival house and every single piece of archival footage that we could find and it required a crazy amount of work. My partner in the film Keith Gionet, my executive producer/archival producer, spent so much time going through every single log and getting stuff transferred, and one of the things that was hard was when [the footage] would come back, we were looking for 15-second [snippets], so we were going through every single piece of that again and again and again and it was all in the effort to really try and understand what happened objectively and the need to corroborate things.

That is exactly it and how to portray that because the more we talked to people, the more we read, the more we saw what the media was showing, the more we saw that dichotomy. We saw that it was significantly different. And the split screen was actually my co-editor Joe Kehoe’s idea. He was like, “I did something a little weird, I don’t know if you’re going to like it,” And it was super early when I watched it and I was like, “No, that’s fucking great.” So we refined it and we worked so much to get what you actually see there, but the idea what you are see, or what you are fed versus what’s actually happening, there was no other real way to understand what happened. That’s what it was because you assume [the media at the time was] telling the truth. You assume that their portrayal was accurate and balanced, but it wasn’t.

This may be a reach, but I had drawn a parallel between this and 1982 in learning about the context of your upbringing later in life – did that make you and Mike Jr. bond quickly?

It wasn’t as much conscious as it was an exploration of the things that I love to explore. It’s fatherhood, love and appropriate representation and overcoming odds through love and determination. Those are things that Mike Africa and Tim from “1982” both share is they loved their families and they were willing to do whatever it took. But if you actually think about it, you could probably describe both movies with the same sentence – if you think about a black man who’s willing to do whatever it took to protect his family, and it’s funny, and this part was unintentional, but if you go back and you look at the very end sequence of “1982” and the ending sequence of “40 Years a Prisoner,” they kind of mirror each other with sort of this home video-esque credits sequence. I cut both of them, and it’s what made sense for this.

I’m going to pop in my DVD of “1982” after we get done talking. As you said earlier, these things that happen in the film sadly haven’t gone away over time – were you editing over the summer as all the craziness was unfolding and did it affect anything?

When I started [four years ago], we were in the craziness then from Baltimore and Freddy Gray and all of those things and at that point, I thought that it couldn’t possibly get any worse. Cut to a few years later and it did get worse. So what happened this summer has been happening my entire life and I’ve known people who are going through those things, so it’s not any different. It’s not any more or less important than it was prior to. The rest of the world is just paying attention now.

You managed to make the premiere at the Toronto Film Festival really special even though it had to happen virtually as a result of the Coronavirus — you got to surprise Cameron Bailey with some surprise guests and you showed the film to your subjects right before the Q & A happened, so their reaction was completely spontaneous. What was that like to pull off? [minor spoilers ahead – watch the Q & A after seeing the film]

It was the first time I’d been on a plane in seven months and I wanted MOVE to see the film before it was out in the world. I didn’t want them to feel blindsided, so I did a very small screening. There were 15 people at the Philadelphia Film Center theater in downtown Philly, a 450-seat theater, 15 people and we watched it and it was a really special experience for a couple reasons. I’m not an emotional person, but sitting there watching it with Mike and his wife and Mike Sr. and Debbie and watching Mike in the beginning talk about how he just wanted his family and why he was doing it and why he was continuing to fight, I was there with him for years after as he tried to do just that and it was a lot for me, knowing what that real life journey was, with disappointment after disappointment and rejection after rejection. Then to be able to watch Mike and Debbie watch the film was really cool, particularly when it got to them seeing for each other for the first time in 30 years. Then there was a MOVE member who for three-and-a-half years of doing this project and being around them, she was just shy and cold — it came out of a place of the misrepresentation of [MOVE] in the media for so long. And after the movie, she did a complete 180. She just melted, and she was incredibly happy with it. Even though it was still in the middle of COVID, this woman who had never touched me in three-and-a-half years, she gave me a big hug and for her to do that and for Mike and Debbie to be as happy as they were – and this was a warts and all story on all sides, but it was a balanced, honest portrayal, [which] was something that had never been done for them before.

“40 Years a Prisoner” will air on HBO on December 8th at 9 pm and will be available after to stream on HBO Max.