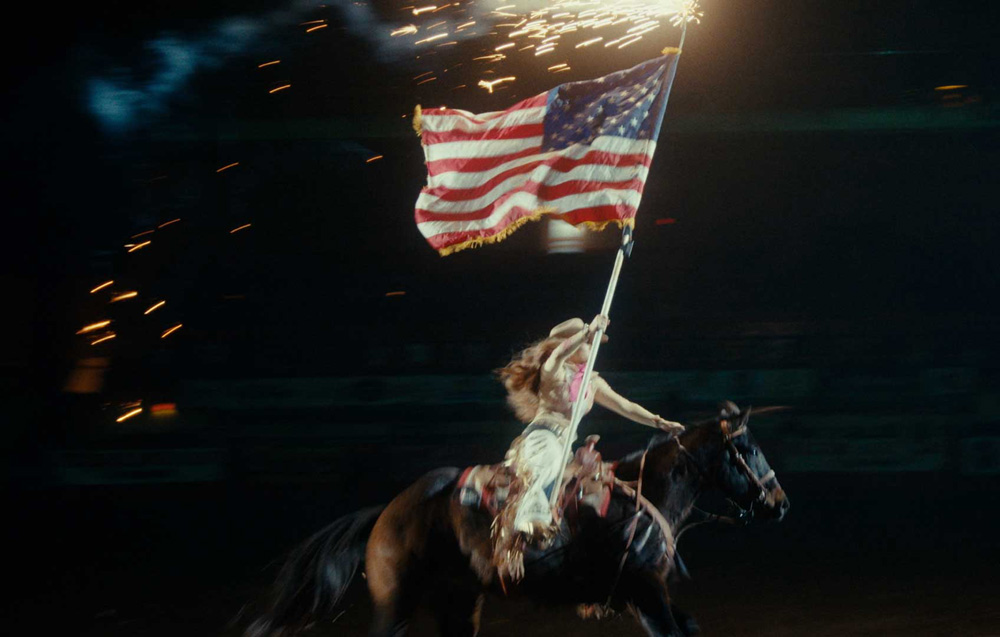

As long as there are new frontiers to conquer, the West will be alive and well to go by Razieme Iborra’s debut feature “How the West Was One,” in which the director expands the definition of a cowgirl by observing three young women expand their horizons. There may be no land left to settle when Iborra starts in Livermore, California where Morgan Laughlin, who has grown up on a ranch tending to livestock, but still she seeks to change the minds of her parents who are surprisingly resistant to the passion she’s developed for the pageant world as Miss Rodeo California, when neither rodeos or the cattle business more generally has been lucrative for the family. Far closer are Ellie Barbeito and her father in Florida, where the former, a fashion designer, has come back from her college years in New York to help out with her dad’s business as one of the few licensed python hunters in the state and has found a utility for what they catch when incorporating the snake skin into her designs, and sees the opportunity to help out with the ecosystem in the state as a whole when looking at the agricultural impact they could make, and while she attempts to move mountains without relocating from the Gulf Coast, the film also follows Annie Bercy, a filmmaker from New York headed towards Hollywood, eager to make movies that reflect her experience as a Black woman after being deprived the opportunity to see herself on screen growing up and starting to lead by example in earnest as she drives across the country as if her car were a stallion in a Raoul Walsh picture, visiting various landmarks of Black cultural history.

At first, it might be difficult to see the connections in “How the West Was One” when the goals of Iborra’s three subjects are entirely different beyond their distance one another geographically, but when all are fighting to be seen in a different light, the director offers them the most powerful Klieg lamps she can muster, positioning the trio against one of America’s greatest iconographies and finding that even in a country where paths now seem predetermined, there are many making their own way forward on their own terms. Iborra allows form to mirror function when she makes a free-flowing documentary that eludes a traditional structure where her subjects speak their minds in a stream of consciousness and the film ricochets from one part of the U.S. to another as a proximity starts to form between the experiences. Recently making its debut at the Dances With Films Festival in Los Angeles, the film opens up the imagination as much as it reflects the reality that is and Iborra graciously took the time to talk about how she set off on her own adventure, the discoveries she was surprised by in her own adventure and realizing what she needed to bring together on her own.

I didn’t come from a horsey family, but I grew up in rural Ohio and I was a horse girl in middle school. I’ve been riding since I was seven and begged my parents for lessons, so I’ve been immersed in this Western-adjacent world from a very young age. And around 2019 when we saw Lil Nas X and “Old Town Road” really exploded across pop culture, it was a striking image to me as someone who grew up around horses and have been riding for a long time. It was still strange for me to see people of color on horseback and I really wanted to examine why I thought that, so I started to uncover all this amazing history of the Black cowboy. I really wanted to put a project together to give more visibility to that history and the project grew from there.

How did it take shape when you find these three stories?

At the same time I wanted to put that Black cowboy history out there, I had these other kind of cowgirl stories floating around in my periphery. One of them is Elle Barbeito, the snake hunter cowgirl. I met her when I was in New York and she was in school for fashion design and I was in school for film and we had a mutual friend that introduced us, so I kept up with her and when she started hunting these invasive Burmese pythons in the Everglades and using their skins for her work, I just thought it was so badass and so cowgirl, but not what you would normally think of. So I roped her into the project and I followed for several years into her practice, hunting these snakes and her work very organically started to have a very environmental conservationist kind of lens.

Then at the same time, I discovered the rodeo queen competition, which was also striking to me because again I grew up riding but I didn’t know about these pageant girls at rodeos, so I started looking for a rodeo queen to bring into this and every state rodeo queen goes to compete for this national title of Miss Rodeo America in Las Vegas, so we put some feelers out and we knew when we started to get state rodeo queens involved, we would follow them to some rodeos throughout the year culminating in the pageant in Vegas. Then Annie, our Black cowgirl is based in New York, but she was looking to move to L.A., so we started building this narrative around [her] uncovering some of this history. One of my own big introductions to Black Cowboy history was the Black Cowboy Museum in Houston, and I had an existing relationship with Larry Callies who runs the museum, so that was definitely a place when we sat down, we were like “We want to go here,” but other places we just stumbled across like the honkytonk called Whiskey River North in Houston, and it was definitely a mix of [places we knew where we could] explore this history and then what we came across naturally.

I had to ask about the day that you see the aftermath of Annie getting stopped by the highway patrol. What was that experience like?

It was wild because that was in Texas and she was driving and stopped for speeding. It was just one of those cases where it really flipped my expectations of what I thought about what it might be like to be a Black woman in Texas. We both were from New York at the time and moving to L.A., these very liberal bubbles, and I think sometimes when there’s a discourse about the South in urban centers when we see issues like abortion on the chopping block, I had certain expectations where I thought we might run into some trouble or some prejudice as we were making the film in these southern states and that wasn’t the case at all. That traffic stop was a perfect example of that. I [thought] “Oh my God, here’s a white cop and a Black young woman who’s driving and we’re in the middle of nowhere. Is this a moment that’s going to escalate?” And I think that it just goes to show that we have a lot of expectations on both sides of the aisle about the other that when you go out and you physically meet people and go to places that you’re unfamiliar with, those stereotypes are not always going to be met.

That was really well-reflected in the establishing shots that you have. What was it like creating a sense of place for these characters and just the general style of the film?

That was really well-reflected in the establishing shots that you have. What was it like creating a sense of place for these characters and just the general style of the film?

When I started making the movie, it was a much more political movie. It was going to open on election day of 2020 – we shot with all the girls on that day and it was going to be a much more heavy-handed. But what it became, especially as I had these experiences in these conservative areas [where I saw] both sides really just wanting to talk to each other, the choices I made in the film from that point forward was to [create this] unabashed, unbiased scrapbook of the America that we’re living in that exists around the peripheral of all three of these girls. So you do see Trump signs and “fuck Biden” signs, which as a tiny documentary made by a girl living in a big city I think some people might see it and be like, “Oh wow, why is that in there?” but I wanted to be very honest about the place that we’re living in [right now].

Also, I wanted this sense of exploration very present in the film of the every day as we figure out as young women who we are, especially in the context of a very complicated America, so coming from a more scripted background and as someone who really likes dreamy movies, I wanted to make something [where] I would want to invest in that story and [something more traditional] like talking head [interviews] never felt like it would serve this story because I think to follow along with three young women is a very experimental thing to do. Womanhood doesn’t have a formula, and the kind of film that attracted me as an audience member was something that was going to be more poetic.

If it’s not spoiling to ask, you actually do bring them together – what was it like after following them all separately?

That was a last-minute [scene], literally in November of last year. The film was finished in February of this year, but I reached out to all the girls to get them together to do some promotional photography in November and it was really my producer Alec Shangold, who’s incredible and said to me, “The one thing that everyone’s been saying in test screenings as we’ve shown cuts to people is ‘Do the three girls ever meet?’ And ‘do they get along? Are they friends?’” And the film is called “How the West Was One,” so I was like, “We’re going to have all these girls here. Let’s just pop off a B-roll shot of the three of them together and see if it works — something simple. I knew that we were going to have this end montage moment with a bunch of different cowgirls coming together, so as soon as we shot it and put it in there, it was like a no-brainer. It’s now one of my favorite moments in the movie, but it almost wasn’t in there.

Amazing. What’s it like for you being able to put a bow on the experience as a whole now with the premiere?

Wild. I’ve spent so much time making the movie and then have been very actively invested in the edit the last year, so now I’m just like, “Okay, we’re here.” It feels very surreal, so I’m excited to actually premiere it and then get it out into the world after that.

“How the West Was One” does not yet have U.S. distribution.