Rashid Mashawari knew that there were plenty of things to be wary of as he began to organize “From Ground Zero,” an anthology film that would allow Palestinian filmmakers to share stories from their homeland in the midst of the war that has consumed the region since the fall of 2023. However, he couldn’t imagine that after the arduous process of providing filmmakers the wherewithal to collect footage and ensure as safe a production as possible, the transmission of those films to the public would require just as much care when the truth of life in such a place can be abrasive.

“We had a big problem with sound because you have this drone [sound], that’s 24 hours a day and it’s in all the films, in all the shots and sometimes it [overlaps] with the [dialogue],” says Mashawari. “We needed to keep [that sound for audiences] to understand what they are, but you need to have a better [presentation], so there were professional people who made a good filter and [did] sound editing because we want to stay real. It was a big job.”

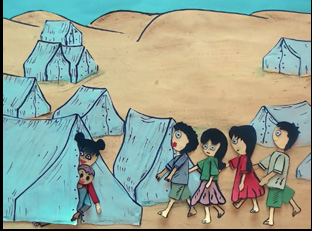

Now on the shortlist for Best International Feature at the Oscars, “From Ground Zero” is poised to have a big impact as a collection of 22 shorts that capture life in Palestine as it exists right now begins to roll out theatrically in the U.S. and abroad. With filmmakers given few parameters besides a run time of seven minutes or less, the film has a bit of everything formally from animation to documentary and shows the reality of a region struggling for resources when its infrastructure has been completely destroyed, with the long waits for clean water a recurring sight throughout the films, as well as the dreams that residents have for both themselves and for their community that they’ve had to put on hold.

It is remarkably bittersweet to watch Ahmed Hassouna’s “Sorry Cinema,” addressing such stasis directly in realizing that the film that’s receiving the international attention he’s always craved for his work comes when he’s essentially had to give up on pursuing a career in the arts to tend to the more immediate concerns, and Hana Eleiwa’s “No,” seems like a similar triumph when ultimately putting scenes in the viewer’s mind that the filmmaker suggests would be impossible to capture under the circumstances in conversation with another. While films such as Rhabab Khemis’ “Recycling” observes ingenuity for survival in looking at how far a jug of water can go being reused for washing clothes, bathing and boiled to feed plants, the obvious limitations on filmmakers to express themselves lead to such inventive films as Bashar Al Balbisi’s “Charm” where kids’ imaginations are allowed to run wild with construction paper.

Still, as can be seen from Etimad Washah’s “Taxi Wanissa,” in which the filmmaker explains how she had to abruptly end production to tend to the tragic loss of loved ones, “From Ground Zero” shows what a precarious and dangerous situation it remains without a ceasefire on the horizon and the film offers perspectives that elude the nightly news. Recently, Mashawari generously took the time to talk about how this timely project came together against all odds, creating a pipeline that could allow filmmakers to see their vision through and an his undying faith in the power of cinema.

I had the idea to make these films in Gaza since December 23 [of 2023]. All the world was watching the news and what you can watch is ambulances exploding, buildings are falling down, and martyrs all the time. People are describing the suffering and parallel [to this], there is Israeli campaign to say we are terrorists. It means that we are cutting heads and killing hands and raping women and we are ISIS. So I thought cinema can do something here, far from the news, far from any politicians or any interest in any direction, cinema can protect this memory.

But we were not sure that we could make these. We were aware of daily life on the ground there. I am from Gaza and I have friends [there] and [know] many people who deal with art and culture in Gaza, so it was not difficult to contact people or to [have] other people contacting people for me. And [I thought] cinema can [allow] us to share these stories with the world because it can bring them closer to the scene, not through news, but through personal stories, so I wanted the untold stories. But we don’t have equipment, we don’t have crews. We have some small things here and there. Some of these films were made by mobile [phones] actually, but [this was only made] out of believing the power of cinema, out of being Palestinian from Gaza, and having all these contacts.

From what I understand, there was a pitch process, but were you reaching out to filmmakers you knew or could people contact you?

It was important to let the filmmakers to come with the ideas because they are living the daily life and I wanted them to express their own feelings and emotions. This is why in most of the films you see the storyteller is also the story. I also wanted them to express their own artistic way of filmmaking, so this is why you can find films that are fiction, documentary, video art, animation, and even marionettes. Everybody was interested in [their own] way of telling their story. We were advising all the time because this project was also a kind of workshop, training beginners to make films in this situation under the war.

What was it like creating a production pipeline, either in terms of getting people help in terms of the mentorship you’re describing or handling equipment?

This was the most difficult part because we don’t have experience to create any strategy or system [to make this]. There’s no safe place in Gaza and we cannot plan because we don’t know what will happen tomorrow. I’ve made many feature films and usually we are sitting around a table two, three months before the shooting, planning for pre-production [with] rehearsals, training, equipment, and everybody knows filmmaking. Here, if there is no electricity, nobody can talk [to each other] because nobody can charge [their] mobile [phone]. You cannot charge a battery, you cannot charge a laptop, and there’s no internet for three or four days at a time. And sometimes we need to be awake without sleeping three, four, five days because there is a [place] where there is a good internet next to one journalist or a hospital or next to Rafah border where Egyptian SIM card can work, and if we want to use it, then we have three or four days upload material and receive material from outside.

So I had assistants and advisors in Gaza, but I had different people — directors, producers, filmmakers — out of Gaza who were working with the filmmakers — Palestinian women from Egypt, someone from Lebanon and from Jordan, some Tunisian and we had a French team organized by Laura Nikolov at the French production company Coorigine Productions. They were responsible for the post-production, receiving, collecting, and cleaning [the materials].

The first thing we learned that it’s difficult to show 22 short films, each one between three to seven minutes in one [sitting]. Emotionally, it’s difficult and as a story, it’s very tough. First, we decided to show it as two parts. You had a break after 55 minutes and to continue like you create a new beginning. Second, we tried to deal with this as a longer film through the order of the films. Even if you have documentaries or you have fiction, you could be in a certain area to talk about love or introduce certain subjects, [such as] missing the people who are still underground. Then when it is very tough [for a while], you go to [a segment about] music or to someone whose dream is to do stand up comedy. We were dealing with this drama as one film and I am very much happy with the end [in particular], with the last film [where] the last sentence they say in the last song in the film, “They will start to destroy, we will start to build.” This was the [right] end.

I was quite moved by it. And as you alluded to, a lot of the films become stories of their own making. The most dramatic example is “Taxi Wanissa” where the filmmaker has to address the fact that filming had to stop to deal with tragedy. Did many of these come back a lot different than what you could imagine?

Most of the films, after we selected the filmmaker and agreed on the idea [of the film], we worked together to develop the story during shooting by considering the situation on the ground, so some stories changed because the reality interfered. “Taxi Wanissa” was one of the examples where for sure we were not expecting that one day after this filmmaker started to shoot, they bombed the house of her brother and he died with all his kids. Life is more important than cinema, and actually we are making films to help to serve the life of a human being, so we’d stop everything and only after some time, we’d say, “Okay, let’s find a way [to continue to film].”

I remember when we contacted Hana Eleiwa to participate in “From Ground Zero.” She made video clips, not film and she said, “No, I can’t. I never make films about suffering. I make [clips] about music, about dance, about love.” But I told her, “Go, find your [own] subject and make a film.” So she found this music group and she made a film about it and the film is not only about the music group, but about hope, [and we designed everything to be] about the filmmaker. There is some other examples like “Sorry, Cinema.” Actually, he didn’t want to make the film, but [the film became about] the fact that he didn’t want to make “Sorry, Cinema.”

Yes, it changed for the positive because most of the time I couldn’t believe that we could make it. What did not change the entire time is my belief in the power of cinema, the power of images, the power of telling stories and exchanging cultures through art. I’m over 60 years [old] now, and I started when I was 20, so the last 40 years, I’ve been telling our stories to the whole world. I’ve had films in Cannes, Berlin, Venice, Toronto, and in America, and I was talking about hope, about life, and about love. I want cinema all the time to participate and to add or invent hope. I want cinema to take care of supporting justice, supporting humanity, and I know this achievement will be there because I trust cinema.

What’s it been like to bring this particular film to audiences?

I’ve been happy in most of the screenings, but the difficulty was that people are watching films with solidarity and with big emotion, but when I am sitting there, I am watching our life. So I’m touched all the time from another direction because everybody [else in the theater] tomorrow, you have other things to do. But tomorrow I am dealing with this. Not films, but the life. On the other hand, if I made this project to make people feel or to share, and I see it works, it makes you feel good. This is what “From Ground Zero” is for me. As a Palestinian filmmaker, I am involved and I’m doing something, [instead of] watching the news day and night and crying in front of the television. To go and try to change something and to be involved is a good feeling.

“From Ground Zero” opens in theaters across the U.S. on January 3rd. A full list of cities can be found here.