As the son of a Haitian diplomat who grew up in New Jersey and went to film school in Berlin, Raoul Peck has become gifted at translation, but perhaps it would be more appropriate to describe him as having no particular attachment to any specific language as an expression of a culture, be it in words or in art. It’s an ability that has also liberated him from time.

When vocabulary has often been used to obscure the perpetuation of injustice with new words being thrown around to suggest that things have changed, it’s exhilarating to hear Peck describe in “Exterminate All the Brutes,” his ferocious look at how cycles of oppression have repeated themselves over centuries and continents in the service of a dominant white culture, the British and Dutch East India Companies as multinational corporations, a term that no one in the Age of Exploration would’ve ever thought to deem the powerful trade networks that backed the conquistadors whose arrival cleared the way for settlers to displace the natives and the plunder a region’s natural resources, yet brings the ripple effect of their actions into the current era of globalization as vividly into the minds of viewers as their impact can be felt on a daily basis.

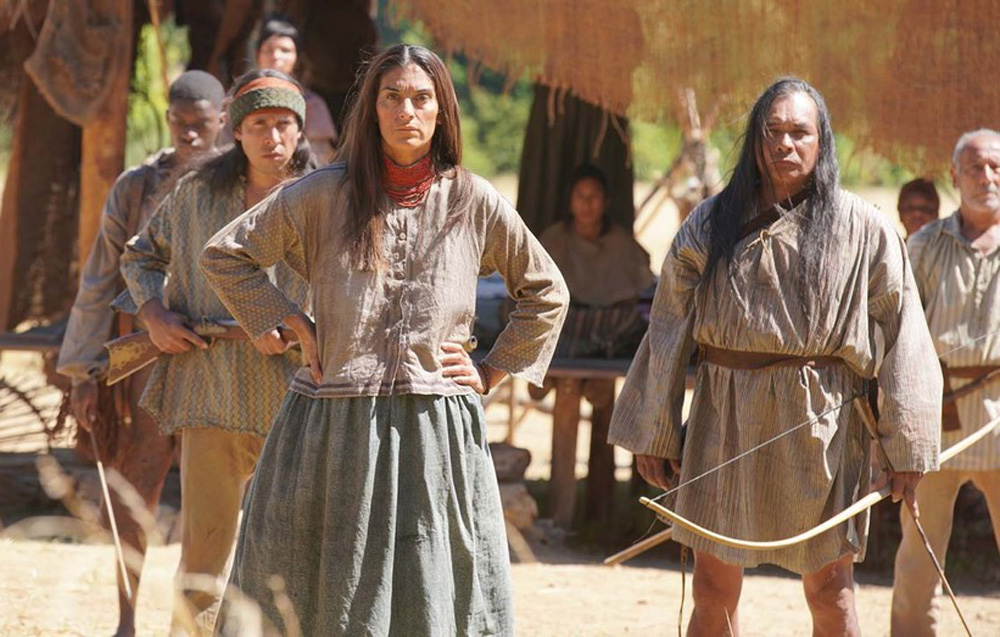

In “Exterminate All the Brutes,” Peck doesn’t only close the gaps between history and cultures to illustrate a global phenomenon, careful to give credit where it’s due in a story where appropriation rears its ugly head time and again when he draws on the work of Sven Lindqvist (“Exterminate All the Brutes”) Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz (“An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States”) and Michel-Rolph Trouillot (“Silencing the Past”) for inspiration for the four-part series. But after moving seamlessly between documentaries and dramatizations that often followed the same thread — making couplets such as 1991’s “Lumumba: Death of a Prophet” before enlisting Eriq Ebouaney to play the pioneering Prime Minister of Congo in 2000 and ruminating on the rebuilding process in post-earthquake Haiti with 2013’s “Fatal Assistance” and the 2014 thriller “Murder in Pacot” — the filmmaker creates a hybrid to impress upon audiences how the reach of white supremacy has extended into shaping narratives around history, showing a grim sense of humor in recasting a role that has routinely been celebrated in school textbooks as one of a heartless savage as he follows a time-traveling white European (Josh Hartnett, admirable in a truly thankless part) who invades communities of color, made to be indistinguishable in purpose, whether he’s among Pilgrims in New England or the various businessmen eager to take advantage of natural rubber in the Congo, as he sees those he’s there to exploit.

With the dramatized portions of “Exterminate All the Brutes” easing one into a rigorously researched reconsideration of history, Peck grows comfortable enough to incorporate his own personal story into the film, offering a powerful rebuke to the dominant narrative in simply expressing how he was able to look past the European version of world events that has softened colonialism and lets its perpetrators off the hook without consequence. Like his previous film “I Am Not Your Negro,” the filmmaker brings such intimidating subject matter that can feel so far away intimately close with such personalization after doing the same for James Baldwin, dislodging images and ideas that may seem fixed in time with the vibrancy of his voice and his consciousness and respect of the pop culture that emerges as a form of resistance to the times in which it’s made. While adding to that tradition, Peck actively dismantles another in need of such a corrective and on the eve of the film’s premiere on HBO where it will be a two-night event starting tonight before streaming on HBO Max, he spoke about how he was able to open up the opportunity for everyone to see the world as dynamically as he does.

This seems urgent in a number of ways, but formally, this seems like you’ve been waiting for a moment to really break with conventions and create a blend of fiction and nonfiction elements. Was this an exciting prospect for you?

It’s something I always did from the start. Even if you see one of my first documentaries, “Lumumba: Death of a Prophet,” it’s about telling a story and constructing my own history — I have to recreate because it doesn’t exist anywhere on the screen and I always make sure that I tell the narrative, whether it’s in the documentary or [a fictionalized account], precise and exact like a history book. But I am in the field of filmmaking, so I make sure that I tell a story with passion and dramatic emotions, and this film is probably the first I formally break the walls of documentary, but it’s the continuation of “Lumumba: Death of a Prophet” and “I Am Not Your Negro.” “Exterminate All the Brutes [would not exist] without [these] others. I would never have dared attempt that.

When I start a project, I always want to do the impossible film because the content alone is not enough for me because content is always linked to form. That’s all we were raised, that’s how propaganda works. That’s how the dominant narrative works. Hollywood is successful because it channeled the content, it channels merchandise, but it’s also channeled form, so for me, it’s always part of the equation. But here, it was particularly complicated because I was dealing with an enormous amount of material and not always having the images for it, not sure of how I would be able to cross line every scene and remain on my feet, so I had to take it step by step and add layers as I went. The narrative scripted part I had in my mind because I know how to do that. That was my strength is that I’m as experienced in documentary as I am in narrative, working with actors, so I knew what I could get from an actor and from scripted material, so I then decided to use it for as an additional tool and make sure also that it’s not going to be what sometimes they call docudrama. No, it has to be fluid, like “I Am Not Your Negro.”

You don’t ask the question in “I Am Not Your Negro” if it’s documentary, archival or [a fictional treatment]. You just follow a character — Baldwin — and once you have that, people don’t question it, so I had to find the same kind of character, except that there’s several characters in this film. There’s the Josh Hartnett character, of course, who challenges time and territories and geography and there is my voice, which also tells the whole story, and then my three friends, Roxanne, Sven, and Michel-Rolph. So I made sure that you’re never alone. You’re never lost and it’s always personal.

From the film, it seems that you started out with Sven’s book or his guidance, and then it developed into Roxanne and Michel’s ideas as well or did you see them as three separate pillars that you could build?

If I didn’t start in a very organic way, I would be lost because otherwise it’s just mechanical and you don’t feel anything. It’s brainy stuff, but it’s not personal. It’s not emotional, so Sven was the really the starting point and I went to Sweden and met Sven several times, and I could have made the film only with his book, but at some point, [I thought] I can’t just use part of the story of the Native American genocide like this from far away. I have to be in the middle of it because that’s the key moment. That’s when everything totally shifted — the discovery of that big continent. That’s when Europe basically decided to continue in a more organized and radical way what it had began against the Jews and the Muslims, discovering this new continent and saying, “This is mine now, no matter who is there before.” So I had to come back to America and I began to research and see who could be the reliable source for me and, at the same time, be a collaborator.

I was lucky from reading and meeting with people I talk to to [come across] on Roxanne’s book and everything was there. That’s an experience I’ve had over the years is whatever the subject, even if there’s 200 books dealing with the subject, there’s always two, or maximum three, that are good books that you need to read and use. There’s always a key book or person who has it all and in the case for me, that was Roxanne, so we spent the time in New York working together multiple days and Michel-Rolph, I knew him for a long time before and I knew of his book and in the chapter where suddenly I had to talk about the Haitian revolution, I realized suddenly I have the triangle and around that triangle, I have everything. I have in that box this 700 years of Eurocentric history from the pilgrim to Donald Trump.

One of the tensions that I loved in the film was how you were using the soundtrack and pop music, showing the culture versus how it was shaped in such an unfair way. What was it like figuring that out?

Yeah, but the thing is when you see a big mountain you have to climb, if you stand in front of the mountain, you say, “Oh my God, 5,000 feet, there’s no way I can do that.” And if you watch it like this, it’s impossible. But if you just decide, “Okay, there is a path yet, let me take this path. Don’t look up there, just take the path” because the path slowly brings you to another area and you say, ”Oh, I didn’t see it from down there,” and then you say, “Oh, there is a small door there.” And you build layers after layers. That’s how you go. Otherwise, it’s crazy. You will panic because it’s too much, it’s impossible, and it doesn’t make sense at first view.

So you have to choose a structure that allows you to do that and all my films, I have destroyed the typical Hollywood three-act structure because it’s a way to contrive you. It contrives the words, it contrives the thinking because you need certain steps — exposition, contradiction, and then resolution at the end, if possible. And once you have that, that means your brain has to find a way to enter that box. But what I do is I explode the box from the get-go, always because it frees my mind. And the next step is you have the music and you have the image and I decide to confront both and confronting both creates something new that I could not imagine before I try it on the editing table.

That’s also [where] a film that is constructed on the editing table, and in this case, many different editing tables — we are inventing as we go. line by line. Somebody’s working on the graphics and [there’s] another group dealing with the archive and one archive can trigger something else, [like seeing] one character in an archive, I say, “Oh my God, can you find me more of this person here?” And [we’ll] look in the archive in South Africa or find in a Russian archive. It’s a detective work. Each piece brings another piece or bring context to the preceding piece, and you do that with images, sound, music, drawings, animation, and the last aspect of that is I am dealing with the history where I am not represented. My archive doesn’t exist, so I have to recreate my archive through the deconstruction of the existing archive. When I play with the picture of Stanley and Kalulu, the picture exists and the picture tells a story, but it’s not my story, and I need to tell my story, so I use the picture in a way that I deconstruct it, I go behind the behind the mirror.

What was it like making it during a time in which you could really see the inequalities come to the fore during a pandemic? Was it affirmation of what you were doing?

The thing is I work the other way around. I collect my experiences, and I come to understand something and I make a film to explain what I understood or what I felt, so I don’t have a journey in the making of it. I’m not different when I finish. On the contrary, I’m relieved when I’m finished because I was able — or not — to express the vibrant experience that I had very different subjects, and that’s my guiding light. Otherwise, I would be lost. To go into a project like this without knowing what you’re talking about, you’re dead. There is no way. On the contrary, what kept me going and kept me in line is that not only did I have those three books and those three companions, but also I have my own life. It’s crazy. I live in the Caribbean. I live in the United States. I live in Europe. I live in Africa. So this [part of the film] is not through books. Those are real experiences — as a young kid, as a teenager, as an adult, as a student, all those universes. Everything you see in the film, I lived through them one way or the other, so it’s totally organic. It’s not book knowledge, it’s real-life knowledge, so that’s why I could be as forceful as I am, as personal as I am, because I’m not inventing something. I’m telling you something I went through.

“Exterminate All the Brutes” will premiere on HBO on April 7th at 9 pm EST and will be available on HBO Max.