It can be an grueling and tiresome process having to watch cut after cut of a film to refine it to its most active and engaging form, but it’s one that Raoul Peck always looks forward to.

“It’s funny because my editor Alexandra Strauss, who has now accompanied me on six movies, and I are sometimes in the screening room and we laugh, we cry — we are good spectators of our work,” Peck said recently. “I like to screen [every] once in a while, because it gives you a different perspective and I make sure that we have this dramatic structure in the film. [A] moment of humor, a moment of irony, a moment of anger, a moment of love [because] that’s what makes you closer to the subject. It pushes you to have your own mind on that because you’re concerned as well. It’s not a foreign story. No, the story has to do with you today, with your life now.”

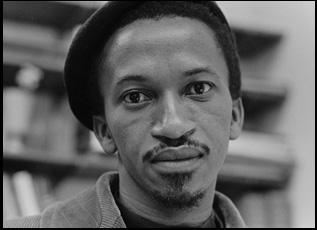

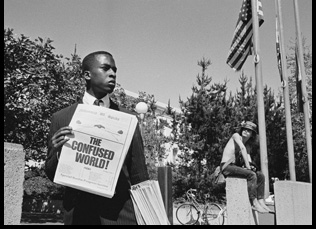

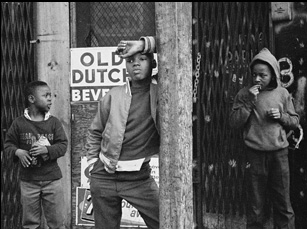

Peck’s demands of himself to reconnect with the material in front of him after seeing it numerous times before has resulted in unusually refreshing films for audiences who can let their guard down when there’s never an expectation to look back despite their historical subject matter, only ahead to see how it’s shaped the world we continue to live in. His latest film “Ernest Cole: Lost and Found” allows you to swim around in the magnificent pictures of the photographer who was born in Pretoria, South Africa under apartheid and eventually resettled in America during the 1960s, having the eye to see that despite the sea between them they weren’t exactly worlds apart if your skin was a different color than white. Needing no more than to train his lens at the streets outside wherever he was living at the time to observe the subtle ways racism can shape a society, his work was feared to have become a casualty of systemic oppression as well when his archive containing 60,000 negatives were long considered lost, with Cole unable to keep them himself as he moved closer and closer to poverty as grants dried up and the rediscovery of the trove in a Swedish bank vault in 2017 led to more questions than answers.

How Cole was met with such an ignoble fate after making a name for himself with the landmark tome “House of Bondage,” a rare and comprehensive view of life under apartheid from a Black perspective, is surely a tragedy, but Peck refrains from ever presenting him in those terms. Instead, one can marvel at how the photographer carried on with such a heavy burden, affording others the opportunity to see things as he did and just as the director recruited Samuel L. Jackson to summon the soul of James Baldwin in “I Am Not Your Negro,” he enlists LaKeith Stanfield to give voice to Cole, drawing on the photographer’s own words to describe an existence in eternal exile, with his focus only sharpened as an outside observer with the knowledge of what he had been denied. Although the photos themselves remain as striking as when they were first taken, they have additional pull in how Peck is able to present them with Cole vividly describing the stakes involved that might go unnoticed by those who are privileged by their racial identity or class, looking no different than the current moment except for the clothes and a few architectural details. The director also makes plenty of room for the curiosity and delight that was a part of Cole’s work as he explored how marginalized communities found pockets of joy that could enable them to endure.

When Peck has long sought to put the people on the big screen who expanded his own perspective of the world, the films bear the intimacy of autobiography even as he recounts others’ lives, accessing emotions as much as documented fact to make them present again and “Ernest Cole: Lost and Found” is the filmmaker at his most exuberant. After premiering earlier this year at Cannes, the film is now rolling out into theaters across the U.S. and Peck graciously took the time to talk about how he could see himself in Cole, digging into archives that hadn’t been available to the public in over 50 years and always keeping an eye on the bigger picture.

A film for me, especially if it has to do with archive and the preservation of our memories and of our history, always has a value for me. Maybe I would not have directed it myself, but I probably would have produced it some way, but as I started digging into the material they had sent me and that my team had started to assemble during those two years, it was clear to me that I had all the layers in them that I usually need to tell a story — the historical part, the archival part, the incredible trove of riches and material and photos that existed. The personal story, both Ernest Cole’s story, but also my own organic stories during those times. I went to Berlin to study when I was 17 and that was exactly the atmosphere [I experienced with] all the liberation movements in Berlin, most of [the people there were] in exile. Few of them to study, but most of them in exile because Berlin was an asylum city, both West and East, so [that generation Ernest was a part of] were my elders. I was trained by them. I was introduced to politics by them and returning to that time, it was rediscovering for me things that I went through. Coincidentally, it was also in Berlin that I started photography, so there were multiple connections that enabled me to do an organic film like I like to make. It’s something that is beyond just making another film.

The question at the beginning was there are two ways to go with this film. There’s this incredible film “Looking for Sugar Man” [where we could do something similar in] sticking to the discovery of those photos, but as soon as I made the decision that Ernest Cole was going to tell his own story, the decision was out of my hand in that sense that I had to follow what is more important for Ernest Cole. What does he have to say and what does he want his images to say and to become and to be preserved? The choice was very clear then, and I didn’t want to soil the movie with another story that I think is ugly enough in itself. [The disappearance of the pictures] is not a pretty story. Why would you hide for more than 40 years that you have the whole body of work of this photographer, who died poor and lonely? Was it shame? Frankly, I didn’t want to indulge in that and being an artist myself, what you want is that your work survive you and continue to do its work. I hope [a film like] “Lumumba” will educate many other generations after I disappeared, so it was not difficult for me to understand what was important for Ernest [as far as what story to pursue].

Don’t forget, he left us with an incredible masterpiece “House of Bondage,” and of course, I studied that very deeply — every word, every chapter. The writing is incredible. So after working on it for many, many months, you do get the sense of how he thinks, how he writes, how humorous he can be, how critical he can be, and how harsh he can be towards certain subjects or elements. Once I had that, I could afford to be more playful, and the approach of penetrating inside the photo is something that I traditionally do in my films, but that connected perfectly about the way Ernest analyses society. I’m making a film, not a didactic work with numbers and dates. That’s the condition number one for me. So I thought it fits in the movie to go beyond the flat photo and go inside the image, the same way Ernest tells you about what is going on in his head when he’s photographing. When I had that example, I had that feeling that I was right to go there.

“House of Bondage” not only had those incredible pictures, but he wrote incredible text to accompany this book and the texts are not commentary to the photos, but they are context for [why] he took those photos and what’s not in these photos, so it gives you the instruments to read those photos. Then when I started working in this multitude of photos and contact sheets, I had guiding lines. To give you an example, I knew let’s make piles of certain photos [such as] the photos of the mixed couples. It was clear that was a thematic that would come again and again. The children, the women, the men in the subways, etc. And I was able to connect that to my own [experience] as a photographer. I know what it is to roam in a city, trying to get one picture, trying to get one atmosphere, trying to get one moment. I know how much walking you have to do. I know how many “no”s you get from people. Sometimes [it’s with] a smile, but I know that from roaming a city and I could go into his head.

Reading the contact sheets, if there are 10 or 20 photos of the same subject, you see which one you choose and try to see why and there are all these instruments to understand how you work. I thought it would have been more difficult, but then you make decisions, you are basically telling a story. You are doing a screenplay and after a while, you know when you’re going overboard, so it’s as precise as that.

That’s even the basic requirement for me because all my projects have to be organic with my surroundings, with my life, with my fights. I grew up like this — in all those worlds. I know what exile is. My parents were in exile and I have friends [there], so I know what how paranoid you can be when you are alone, isolated in a place that is not your country. I know what the struggle is from abroad when your country is under a dictatorship or an apartheid regime or is in war. I know how those communities live and [how] on a daily basis, you are connected to where you come from. Even if you become an American, you have your nationality, but your mind still follows [everything] because you have friends or family and you heard on the radio or today on the social media, so and so was killed or kidnapped or arrested, so it’s not something you can just push aside. You live through it.

For me, sometimes it’s worse because I live through it [from all the places I’ve lived], whether it’s Congo, whether it’s Haiti, whether it’s France, whether it’s the U.S. I have connection there and I have people who are very close to me. [This recent U.S. presidential] election, I could say, “Well, I’m not all the time here, so who cares?” No, I know this election will cost the life of many people throughout the world, so, you live all the time. I quote Godard sometimes, from “Ici et Ailleurs,” like “Now and this other place, they are both in your head,” so my films have to reflect that. The little bubble that we sometimes now are engulfed in, it’s an illusion. It’s forced because the world doesn’t stop existing because you are in your bubble. It’s not because you don’t see it. It’s not because you don’t think about it that it ceases to exist. That other world has an influence on your life. You can choose not to see it, but it’s directly linked to your life and on the other side, what sometimes your government does in your name has an influence to the life of many people throughout the world, so, for me, it’s essential to be able to make those connections and to connect those dots.

“Ernest Cole: Lost and Found” is now playing in New York at the IFC Center and opens on November 29th in Los Angeles at the Laemmle Royal. A full list of theaters and dates is here.