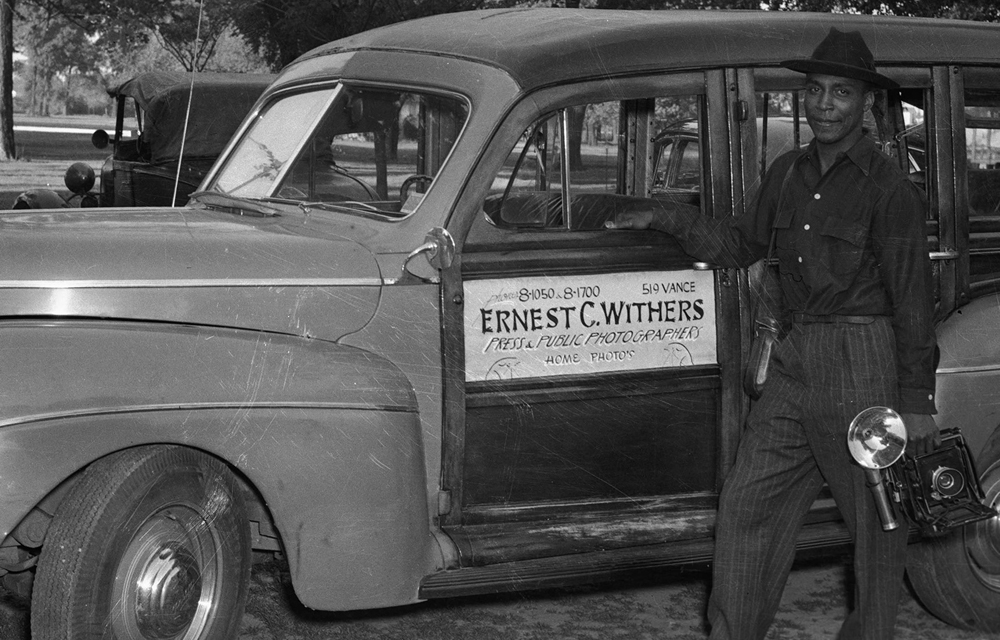

When “The Picture Taker” makes its local premiere as the Opening Night Film of this year’s Indie Memphis Film Festival, there will no doubt be an air of celebration as the late photographer Ernest Withers, whose neighborhood snapshots during the height of the Civil Rights movement that continue to reverberate around the world, is remembered with a vivacious portrait of his life and work. There will also is likely to be a bit of a reckoning when any picture of Withers would be incomplete without reckoning with a secret he kept all his life, only emerging as director Phil Bertelsen began to work on the documentary and learned that his subject had been an FBI informant, providing intel about leaders such as Martin Luther King Jr. and plans for protests to the government that saw the movement as a threat.

No sooner than “The Picture Taker” starts does it jump right into the fray, with loving remembrances of Withers peppered with those trying to reconcile how could do the critical work of chronicling a fight for equality while potentially undermining it with the information he shared. Although that’s a question the film lets linger long after the credits roll, Bertelsen and an intrepid crew show how Withers could be capable of holding both these impulses in his mind, having a strong sense of service early in life after a tour of duty in the military where he first picked up a camera and then returning home to Memphis where he opened a studio and patrolled the streets, both as a burgeoning professional photographer and as a police officer to make ends meet.

Having a strong lay of the land would give Withers a knack for being in the right place at the right time, not only collecting lasting documentation of the Civil Rights movement but capturing the richness of Black life in all aspects as he would head to the clubs in the hometown of Stax Records to be among the first to take pictures of Isaac Hayes, Ike and Tina Turner and Carla Thomas and walk up and down the aisles of Martin Stadium where the Negro League Memphis Red Sox played and offered a rare place for the Black community to come together and enjoy themselves in segregated times. However, “The Picture Taker” wonders what the cost of preserving history was when Withers may have changed the course of it in some unfortunate ways and as much currency as the pictures he took still have today, so too does a conversation about the means he used to keep taking them when his relationship with the FBI most likely made it a sustainable practice.

“The Picture Taker” is not only an ideal way to kick off Indie Memphis because of its hometown ties, but indicative of the provocative, powerful and engaging films that can be found throughout this year’s lineup, an exciting mix that allows for discoveries of up-and-coming American filmmakers with feature debuts such as Eric Younger’s “Very Rare” (October 23rd, Studio on the Square and online) and Elizabeth Ayiku’s “Me Little Me” (October 22nd, Studio on the Square at 4 pm and online) international revelations such as Alice Diop’s “Saint Omer” (October 22nd, Playhouse on the Square at 12:20 pm) and Ellie Foumbi’s “Our Father the Devil” (October 21st at 10:10 pm and 22nd at 10 am, Studio on the Square) and a healthy dose of hometown pride with screenings of “The Vous” (October 22nd, Playhouse on the Square at 2:50 pm and online) about the legendary BBQ the Rendezvous and an anniversary screening of Craig Brewer’s landmark DV drama “The Poor and Hungry” (October 23rd, Crosstown Theater at 6:30 pm).

Even those who can’t make the trip to Memphis this week can partake in the festivities when a large portion of the diverse program is being made available online, including “The Picture Taker,” which will stream for the entirety of the festival following its premiere on Wednesday (and if you’re in New York, can be seen theatrically at BAM through the 20th) and on the eve of its premiere, Bertelsen and producer Lise Yasui spoke about the decade-long journey to get to this moment, doing justice to such a complex subject and needing no reminders of how important this history remains when it only seems to repeat itself time and again.

From what I’ve heard, this project may have found you. What was it like to inherit?

Phil Bertelsen: It was indeed an inheritance. My mentor, St. Clair Bourne, died within two months of the day that Ernest himself died, and by then he had accumulated a few days of footage with no knowledge of this FBI informant angle [for a film of his own]. He set out to make a biography of a little known but worthy photographer who was a kind of Zelig of his time and when I inherited the film some years later, the revelations were just emerging. That was 12 years ago, and over half that time, Lise was on board, producing it and getting it across the finish line with me.

Lise, did you know what you were getting into with this?

Lise Yasui: No. [laughs] Only that I thought it was a fantastic story. And I know Phil’s a fantastic director. I figured with such a compelling story, we could get it done and raise the money within two years at the most, based on past experience. It took us six, but the time allowed us to really gestate this film in a very complex way and allowed us to dig below of headlines and gave us the time to really research it thoroughly.

Phil Bertelsen: In the time that it took us to finish the film, there were no less than two historical nonfiction books written about the subject, a fabulous coffee table picture book of Ernest’s photographs and a podcast, so there was all this accumulating media, which gave us additional information and insight to the story that we could then track down. So we were very fortunate in that way to have the gestation of time and the benefit of other people’s research. But we stayed committed to telling this story as much as we could from the inside out so that everyone we spoke with, with maybe two exceptions, all knew Ernest, all interacted with him, all worked with him, all had some dealings with him and his career.

Since you said that this happened around the time of the revelations about being an informant, were people really wrestling with their own emotions about learning he was an informant as they’re talking to you about this?

Phil Bertelsen: Yeah, some of the early interviews that I did before Lise came on were right on the heels of the revelation, so it was important for me to try to get a sense of how people were feeling. And it was really at that early stage that I got this uneasy sense that people weren’t feeling as strongly opposed to these events as I had expected. And Lise was able to uncover a much broader list of people who may have been impacted and had relationships with Ernest who might have had opinions to the contrary. We were both surprised that no one was really willing to throw him fully under the bus. It was a very nuanced reaction.

Lise Yasui: We weren’t going to oversimplify it or reduce it to labels of hero versus villain. And it takes a while to build that trust. We had to chase a bunch of our subjects for over a year to convince them that we were on an honest journey of genuine curiosity about this event. And it takes a while to build the trust with the Withers family — this was their family’s patriarch, dearly beloved, not only in the family, but within the Memphis community, so as outsiders to Memphis coming in on such a controversial subject, you really have to take your time and meet people and have discussions with them and be transparent about what your intentions are.

One thing that also happened over those six years is Ernest left behind over a million negatives that had not been looked at since he had put them in those little business envelopes in that archive, so over those six years, more and more of those photographs were digitized and saw the light of day, and we were able to tap into that.

When Ernest does seem like an enigma even to people close to him, were you able to discover much about him from the pictures he takes?

Phil Bertelsen: Yeah, it was very clear that Ernest had interest in every aspect of Black life — everything from births, christenings to funerals. The entire scope of the life of a citizen in Memphis was really something of interest to him and what he turns his lens on told us a lot about his interest and his work ethic. It was clear that he really never was without a camera — often he was known to have two, and one he would shoot to sell and one he would shoot to keep for himself, so [he led] just an extraordinary, unpredictable life, to say nothing of the double life that he led, a secret that very few people knew.

It seems like it must’ve taken remarkable patience to get some of the scenes you do in the present day of being at the Withers Museum when Courtney B. Vance stops by or the PRIZM Ensemble wants to do a performance around his work. How did those moments come into the film?

Phil Bertelsen: Courtney B. Vance was something that came to our attention vis-a-vis Ross, a digital photo archivist who had taken an interest in the collection as he describes in the film — [taking the pictures] out of obscurity, out of envelopes from the negative to the digital universe. And they’re still in conversation about that. It involves a great amount of resources, so much so that we couldn’t wait for that to come to fruition, but they were basically evaluating the collection and the scope of it. And it was one of Lise’s first shoot days in Memphis where we had scheduled to go to the archive and see the work there, and we got this late breaking word that he had a client that was scheduled to come in that day. And so there we were when the PRIZM Ensemble came by.

Lise Yasui: One of the challenges of making a film about a subject who’s no longer with us is how do you do you bring it into the present and make it relevant and resonate with present day audiences? So we were always looking for opportunities to try to do that. What struck us as we looked at some of Withers’ photographs from civil rights events, especially from the ’60s, and ’68 in particular, was how much was almost precedent for what we were still going through. The height of Black Lives Matter protests started also during this production and the unfortunate continuation of the killings of young Black men by police and power-holders, and we were seeing it in those photographs of 1968 and before, so we really wanted to try to make a point that even though these photographs could be considered archival, they’re speaking through the generations and through the ages. We [may] overuse the phrase, “The more things change, the more they stay the same,” but that really became almost a motto as we were looking for scenes and ways to contemporize this story.

Phil Bertelsen: Yeah. It goes without saying that to try to make history relevant is really the challenge, and in this case, in walks a man looking for a photograph [of Larry Payne] from a time to help tell his story of this orchestra and this choral ensemble. It was a photo that Ernest had taken, and Larry Payne was Michael Brown was George Floyd was Kenneth Chamberlain. The list is too long. That really ignited in me a sense that this was a story that really had value and meaning to today’s audience and it was an opportunity to show Ernest’s historical work in a contemporary setting, and one of those wonders of documentary filmmaking that just wanders before your lens and helps you tell your story.

The film does an excellent job of being respectful of Ernest’s work while raising questions about his work with the FBI. What were the conversations like when you were putting this together after you’ve done the interviews to portray this complicated legacy?

Lise Yasui: Well, I think we’re still having conversations about that. The truth of the matter is Ernest is not here to talk about it, and he never did talk about it publicly with anybody, so we had to really be careful that we were not taking a side. We all have our opinions. Documentary is never totally objective, but we had to be very careful that we were not leading the audience into one direction or the other, but instead paving the road and the many, many intersections and the paths that Ernest crossed to try to make their own decision because none of us can speak for him. That’s always been what makes this film, I hope, very interesting and engaging for the viewers and pulls them in, and certainly, that’s been our experience when we’ve shown it to people. The opinions are all over the map, depending on the shoes that you personally have walked in to get into that seat in the theater. And that’s very gratifying for us. It might be frustrating for audiences that want a cut-and-dried answer, but hopefully we’ve been very disciplined about not walking into that trap with this one.

Phil Bertelsen: And that perspective, which is a multifaceted one, grew out of our reporting and our discussions with people whose lives were impacted by Ernest informing on them. If they don’t have a strong opinion and opposition of what he did, then how could we? If they could see the nuance and the context of the time and how it has an impact on a man like Ernest, then we ought to, and we owe it to our audience to see that as well.

You’ve had a few screenings so far in New York and it’s sure to be a special occasion at Indie Memphis this week where it’s the opening night selection – what have these last few weeks been like?

Phil Bertelsen: It’s been really gratifying and honestly, I’m looking forward to opening night at the Indie Memphis Film Festival. That’ll be the capstone event, for sure. Bringing it home to Memphis, a place which is so singular and in its people, and its community and its history, all of which have participated in the making of this film, all of whom are going to be in attendance to see the film, I’m just really thrilled to have the opportunity to bring it to the Bluff City for such a big event.

Lise Yasui: It’s a homecoming for us and the film, not only people who are in the film going to be there, but our Memphis-based crew will be there too, and it really was a labor of a big, big, big village to make this film happens, so it’s going to be really great. We’re thrilled.

“The Picture Taker” will screen at the Indie Memphis Film Festival on October 19th at Halloran Centre at 6:15 pm and October 20th at Studio on the Square at 6:15 pm and will be available throughout the U.S. to stream from October 21st through October 26th. It will air in January on PBS.