When making a Looney Tunes animated feature is all anyone in animation could ever want, Peter Browngardt had few other requests when he took the helm of “The Day the Earth Blew Up,” but when the Daffy Duck and Porky Pig adventure started to take the shape of a buddy comedy with a science fiction twist when the duo has to stop an alien invasion that takes root in chewing gum, the director needed to have one thing.

“When Josh [our composer] was putting the orchestra team together, I go, ‘Wouldn’t it be cool to do live theremins?’” Browngardt remembers, once having a co-worker at Cartoon Network who would bring in a homemade theremin to mess around with, and getting his wish to honor films like “Forbidden Planet” and “The Day the Earth Stood Still” that were inspirations for his latest with that eerie electronic sound. “They had a live theremin player in a separate room, and it was so awesome because she was amazing, and then during a break, a lot of the musicians went over, were like, “Hey, play the ‘Star Trek’ theme!” It was so fun.”

Although Browngardt kept personal requests to a minimum, that isn’t to say there weren’t demands on “The Day the Earth Blew Up,” having both the honor and the onus of somehow being the very first to make a proper full-length “Looney Tunes” feature. (Previous forays for Bugs Bunny and the gang onto the big screen had either been compilation films comprised of classic shorts or live-action/animated hybrids like “Space Jam.”) The opportunity to stretch the canvas came after Browngardt, who first made a name for himself at Cartoon Network moved over a few blocks down Olive Avenue in Burbank to help oversee an all-new batch of “Looney Tunes” shorts made for Max in 2019 at Warner Brothers Animation, and he and the team he brought together could clearly be entrusted with the madcap spirit that was initiated nearly a century ago by directors with sharp, absurdist comic sensibilities such as Tex Avery and Friz Freleng.

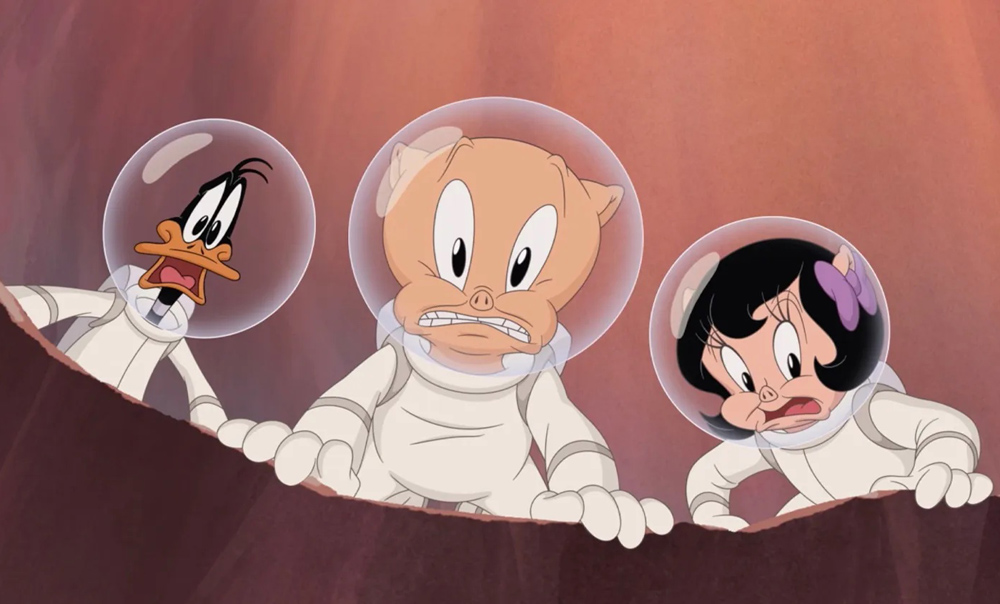

Daffy and Porky may attempt to find work as rideshare drivers at one point in “The Day the Earth Blew Up,” in desperate need of the cash necessary to keep a roof over their heads when they’re threatened with eviction, but there’s no denying that the film feels like classic “Looney Tunes” in every other respect as they end getting jobs on the factory line at Goodie Gums and discover the product may have an unintended otherworldly ingredient that can turn customers into zombies. Along with Petunia Pig, a scientist specializing in flavors at the company, Daffy and Porky have to save the world with what they know and while there is the comfort of watching the two iconic characters getting in the other’s way as they have for decades, Browngardt and crew use the longer form to give an unexpected depth to the relationship as they can’t entirely trust one another despite their longtime friendship and only the threat of a potential apocalypse can bridge the gap.

Still, “The Day the Earth Blew Up” leads with silliness and just as Browngardt knew a theremin would make things more fun, any opportunity to pack a little more into a given frame is seized upon with relish and the film employs the widest possible aspect ratio for not only sight gags but elegant artistry. After accomplishing the impossible, Browngardt recently took the time to talk about the film as it heads to theaters for a year-end awards qualifying run in advance of a general release next February and spoke of how he landed such a plum gig, affording the film’s storyboard artists are ownership over the story, and staying true to the Looney Tunes tradition with a desire to innovate.

Yeah, it was a natural growth from it. I did the Max shorts and people were really liking them. I put together a really great team and even before they came out within the studio, there was a lot of buzz around them. We dove into the honoring the classic Looney Tunes style and humor and those characters, and they asked if I had any movie ideas. I went away for a few weeks and came up with this pitch, “What if Porky and Daffy were in a Ed Wood sci-fi B movie? Surprisingly, they went for it because when you mention Ed Wood, I don’t know if people in Hollywood would go, “Yeah, that’s the movie I want to make,” but I think it made sense to them. It was almost like, it’s sci-fi, which Porky and Daffy have starred in in the past, and they really liked what we were doing with Porky and Daffy on the shorts and we really liked working with those characters making the shorts, so they put us in development, and it moved on from there.

The Porky and Daffy relationship really is enough to sustain a feature and surprises in how it deals with this issue of trust between them. What was the evolution there?

The evolution of that is that we knew early on they were buddies and there were the genre shorts [already], but in the early black-and-white Clampett, they lived together and they don’t always want to kill each other. They’re not Bugs and Elmer or Bugs and Yosemite Sam, and also buddy comedies are something that I love. I love “Dumb and Dumber” and “Shaun of the Dead,” and [Porky and Daffy] have the Ying and Yang personality like Abbott and Costello, so it made it a little bit easier to say, “Okay, I can make a movie out with them, I can tell a larger story with them because they have a relationship and you can put that through its paces.

From what I understand, the storyboarders don’t only sketch out scenes, but contribute their own dialogue, which may be more common than I know in animation, but how does it give the film a personality?

There was a first draft of the script by Kevin Costello that was great, and it got the film greenlit, but animation is made in the storyboard room. Animation is obviously one of the most visual forms of filmmaking, if not the most visual, and especially with slapstick and humor like this, you need the visuals when it plays so much a part of it, so [developing the story] was a lot of hanging out on Zoom calls, doing gag drawings, talking through what could happen and people offering up ideas.

I come from being a storyboard artist and writer and storyboard artists are writers, especially in animation. It’s being like a rewriter on a script a lot of times. Or when there is no script, [a studio will say] “We want to do a part where they’re in the jungle, and the beat is maybe they meet this guy, go figure something out,” and then you’re coming up with it out of thin air. “SpongeBob’s” written this way, and I owe a lot to Steve Hillenburg, who got the storyboard artist writer’s credit on the original “SpongeBob” film. That was a great leverage with me going to the studio and asking for that. You almost become a lawyer going, “Hey, look at the script, and then look at the storyboard and how different it is. This is totally different, and this is writing.” I wish we got more recognition from the Guild because these things make a lot of money, you have to have some residuals, but it’s a step in the right direction. It’s one of my proudest things about the film is that I was able to get those artists the credit.

When you get to do Looney Tunes, you have 40 years of cartoons to look at, and I have every single one on my hard drive. It was something that we put together early on because why wouldn’t you when you have the manual of how to do this stuff. It’s like having the book on how to construct the engine. All the information’s there, you’ve just got to look and analyze it and talk it through, so those are huge not only for technique, but also character and style — how to do dry brush, in-betweens, and smears, and the timing of stuff. I don’t think there’ll ever be a time where artists will have 40 years to perfect something like that by doing multiple versions of it over and over again. You could say “The Simpsons,” but in this day and age, they’re getting locked in and those artists, like the great Disney artists — the Nine Old Men —were always pushing forward and were never satisfied, and tried to motivate the art form.

And with the classic Looney Tunes, you can see the animator’s hands behind it, and we tried to preserve that as much as possible. Putting together people that are at that caliber, there are a handful of artists that are still around and still making stuff like the great Dan Haskett, or Bob McKnight, or James Soper, another character designer I worked with, that can draw these characters the way they’re supposed to be drawn. So we laid out the movie, and we’d get a scene approved for the animatic, and then we would do all the key drawings, and that’s one thing that kept the animation quality and the consistency. Then when we sent the layouts to the animation departments around the world, we’d say “You have to use that drawing, you can’t redraw that drawing. That is a frame of the line art of the drawing. So that was kept, but what you’re talking about and what they did — what Chuck Jones and Bob Klemek did — is they would lay out their own cartoons by doing all the keys for the scene.

That’s was one of the first things we thought of because [we thought], “What are our tent poles, holding the picture up? And one of my first ideas for the film was it’d be so funny to do a short within the short that helps move the story forward, and I love “Who Framed Roger Rabbit” starting that way, and Alex Kirwan, the producer, had an idea for an Art Deco musical number, that he did a little concept piece for. I knew I wanted to do a Sam Raimi meets John Carpenter’s “The Thing” [mashup] with the gum monster sequence, and our art director, Nick Cross, pitched the idea of doing the Farmer Jim [introduction] with Thomas Hart Benton style. “Looney Tunes” doesn’t have a set style — there’s a style to the humor and a style to the animation movement style in a way, but art direction-wise and visually, it evolved so many places over the four decades that it gives you the freedom to [think] it’ll make it feel more like a Looney Tunes movie if we do this.

“Looney Tunes” introduced me to so many different styles of art growing up, which I feel you’re passing along with that approach.

And music! Our composer Joshua Moshier, was like, “I learned so much about classical music from Looney Tunes,” and there’s so many composers that I’ve read in the past that have said that. So much of that Carl Stalling music from classic Looney Tunes were callbacks to classical music but also music from that era and they’re literally called Looney T-U-N-E-S, so that’s half of it., and so many comedians and writers of comedy of our generation and generations past, look to Looney Tunes and go, “I learned how to be funny.” Conan O’Brien, Steve Martin, some of the greatest comedic minds of our time, but the art style is important to the brand of Looney Tunes, and it’s all Tex Avery, who planted the seed that grew the plant of Looney Tunes that just enveloped our culture, and then it was perfected by [Bob] Clampett and [Chuck] Jones and [Friz] Freleng and [Robert] McKimson and all the other great directors involved.

It’s wild. When you’re making this stuff, I never really step back. You’re just living it, and it’s part of your life, and you’re doing it. But just recently I had a couple moments where I go, “Wow, if you went back in time and told your seven-year-old self that you made a Looney Tunes movie, I would have never believed it.” I got Tex Avery cartoons and Looney Tunes when I was seven years old, and I learned how animation was made, and my dad made me an animation desk, and I made Super 8 cartoons and little animations on typing paper with a hole puncher. Now I got to direct this first original Looney Tunes movie. It’s extremely surreal in a lot of ways, and I put a lot of hard work in, but also I was given a lot of opportunity and fortune to have this happen.

“The Day the Earth Blew Up” opens on December 13th at the Laemmle NoHo 7 for a one-week qualifying run. It will open wide on February 28th.