Two months after Nanfu Wang gave birth to her first child, she was planning to fly back to the the Jiangxi province of China where she had grown up to see her family. Of course, it would be a chance to show the baby off to her family, but the visit wasn’t entirely personal. Her pregnancy, coinciding with the relatively recent reversal of China’s “One Child Policy,” which had forced generations of Chinese families to restrict the number of children they had, had gotten her to think about the devastating impact that such a law had across the country and in her own home. While Wang was concerned whether she could ever return after her explosive debut “Hooligan Sparrow” implicated government officials in a cover-up when following the activist Ye Haiyan as she brought attention to the sexual abuse of a group of elementary school girls at the hands of their principal, motherhood had given her new perspective in a variety of ways, including how wearing a Baby Bjorn might give her cover.

“It was a trip to test the waters to see how the government would react and I really felt if the government would do anything to me, I think the publicity is not going to look good to see how they’d treat a new mother,” said Wang, during a recent visit to Los Angeles.

The plan worked and Wang, who didn’t bring anyone else with her but her son and her husband, wasn’t bothered as she began to investigate the period between 1979 and 2015 when the entire country was bombarded with government propaganda touting the prosperity that would follow if parents limited themselves to one child in an effort to combat overpopulation. However, the reality Wang finds is the destruction of families from within as the preference given to males would become corrosive, couples would be haunted by abortions and sterilization aimed at preventing unwanted births, siblings would resent each other and their parents from the social stigma attached to flouting the policy and the thousands that were shuffled off to adoption had no way of knowing their biological origins. Remarkably for a policy that had such wide-ranging effects on an entire nation, Wang needs only to look inside the village she grew up to see the damage, interviewing relatives, neighbors and ultimately those put in charge of keeping watch over the community to understand the extent that the policy directly reshaped a generation and likely many more to come indirectly.

With co-director Jialing Zhang, Wang not only offers a comprehensive history of the policy and turns its effects into captivating flesh and blood testimony, but in filming as China pivots to a new era in which this painful time is likely to be swept under the rug as much as possible, she makes the subtle subversion of the public record or its complete erasure plain for all to see and creates undeniable evidence to combat a future in which the past is forgotten or selectively recalled. Following its triumphant premiere at the Sundance Film Festival where it won the Grand Jury Prize in the World Cinema Documentary section, “One Child Nation” arrives in theaters this week and Wang spoke about how she was able to keep perspective while telling a national story that became so personal, as well as figuring out the tricky logistics of filming in China and discovering the many shades of grey in what she initially believed to be a black-and-white story.

No, I didn’t, especially [since] a lot of my family’s stories I wasn’t aware of. For example, I didn’t think about the shame and embarrassment I felt towards having a sibling [before making this film]. I didn’t know my aunt had given away her daughter and although I knew a little bit about my uncle [once] having a daughter and she died, I didn’t know the details, so it was during the making of the film and talking to people that I realized all of these things happened within my own family and that it was also almost like a microcosm of the entire country. That’s when I discussed with my co-director and producers about how we were going to make the film and [we] made the decision I was going to include them.

Does wearing a filmmaker hat give license to ask questions you might not as a family member?

Talking to them from the role of a filmmaker was surprisingly difficult, more difficult than talking to a stranger because we don’t usually have serious conversations [as a family]. We have superficial [talk] – “Have you eaten?” Stuff like that. So it was the first time that I ever had adult-to-adult conversations with my mom, my uncle and my grandpa and we were equals, discussing something serious – traumas and issues in their lives. And there were many challenges. First, it was how to request talking to them that way and then I went through a lot of debate on whether I should expose them that way and what the potential consequences would be of putting them on camera. Luckily, my family were all very supportive and for one reason or another, they all agreed to talk to me.

You mentioned at True/False that you would edit between trips to China. Would processing the material that way help you find a way forward?

Yeah, the filmmaking was a journey of discovery, so every time we’d film one trip, I’d come back to edit that material and that helps me to understand what the footage is telling me is going on and to adjust my perception about the story. For example, when we met the midwife, [my understanding of the story was] there were perpetrators and victims – bad and good people, but meeting her brought a lot of complexity and made us realize the story’s not black and white. We needed to explore the psychology behind the enforcers [of the one child policy] – the officials – when [we] finally met the officials who were on the other side and realized that they are just as much victims as the others, that shifted the thesis question from what happened to why it happened? Then when we encountered a lot of the propaganda material, that also made us focus on how to understand the effect of the propaganda and the role it played in this entire policy in shaping people’s minds.

You also bring in some interesting voices from outside the village you grew up in, like the artist Peng Wang. How did you come across his work?

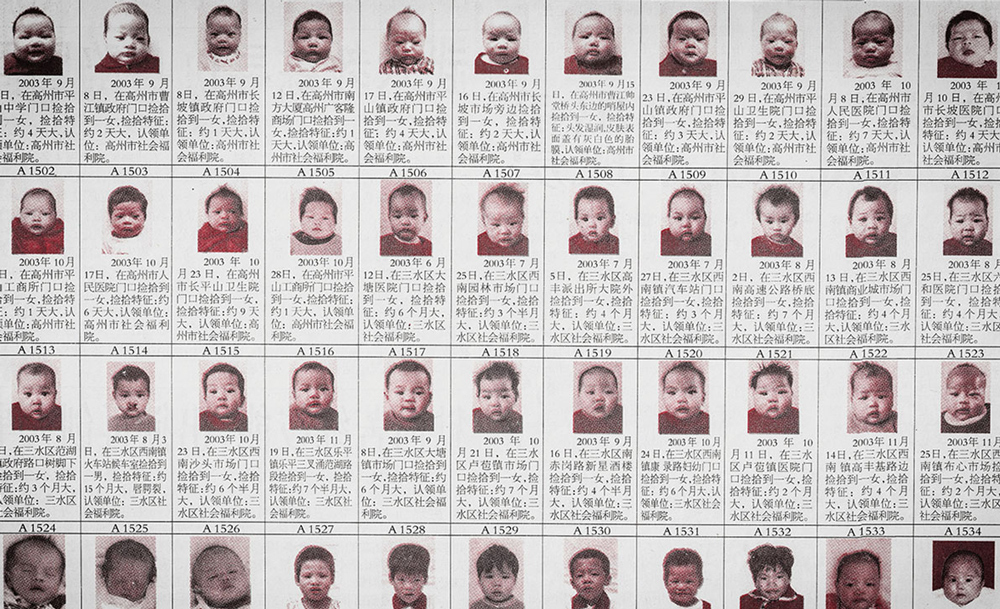

I actually knew him even before I was making the film because there were only a few people who were critical about the one child policy who still live in China. He was one of those who was always very outspoken and would accept interviews from foreign media. He posted his work, the pictures of the babies in the jars and the paintings on the internet, so I was aware of him and [had] never talked to him, but when were making the film, I immediately thought about going to him, so we did.

What was it like figuring out the logistics of a cross-continental shoot?

Going back to China was always tricky because we never knew what would happen in China and how the government would react, so we took extreme precautions each time we tried to go. Usually, I would go to China and my co-director Jialing [Zhang], she would stay in the U.S. and she would help communicate with the subject through encrypted messages, so I didn’t directly communicate with them and there is no trace between the subject and me in case either me or them were being monitored. We would set up a time and place so we would go and at the same time Jialing would monitor me on GPS down to every second, and if something happened, we had plans for what would we do, how do we respond, and what kind of resources could we pull to get out of the emergency as soon as possible.

What was it like having a co-director in Jialing?

It’s extremely helpful. Jialing and I were friends before we started making this film. We went to a graduate program at NYU and she was a few years above me, so even when I was making “Hooligan Sparrow,” she would watch my cut and give feedback and we’d always hang out. Now working on a film together, we have the same goals. We share the same sense of responsibility of being Chinese citizens and we wanted to report the history of the one child policy. We almost felt it’s our generation’s responsibility and it’s a mission we wanted to achieve. I also felt lucky that we have the same creative sensibilities, so we always were on the same page and that makes things extremely efficient because being a director and editing the film at the same time, a lot of times you could lose perspective. Having someone who’s constantly there and bouncing off ideas and looking at it and talking about things was really helpful.

One of the challenges is to find the balance of how much or little of yourself should be in the film and [ask] why you are in the film? “Hooligan Sparrow” and “I Am Another You” are both first-person perspective and because I edited, I knew that perspective of looking at myself [and asking] how do I treat this character versus the other characters and where does she exist? In “One Child Nation,” it was similar, but much more challenging because when I was talking about personal stories and my family’s stories, it was natural to be in the first person, but when it gets to the national and international stories, it was more challenging because unlike the other two films where I shared space, time and lived with [my subjects] and their lives affected my life and my presence changed theirs – this was different because the characters, whether it’s an 80-year-old midwife or 70-year-old official, we didn’t co-exist in the space, except for this short interview. Since I didn’t want to be like a TV correspondent, [offering] commentary, the guideline in the editing was looking at their story and reflect on how their story affected me, whether it’s emotionally or knowledge-wise. [I’d ask] what did I learn from them? How was my perspective changed or shaped by them and I used that to navigate through the storyline.

What’s it been like taking this film around the world?

It’s really exciting, but also very emotional because we’ve met a lot of audience [members] who are Chinese and learned the reality for the first time about the one child policy or encountered a lot of adopted families that did not know their adoptees’ story was sometimes a lie. They’ve learned the truth through the film and it was very emotional for them.

I was surprised to see during a Q & A from the Human Rights Watch Film Festival someone talk up what they saw as the benefits of the one child policy as an only child after seeing the film. Have you faced this kind of resistance elsewhere?

A lot, especially from people who are from China. My friends, my closest friends, my family. I think in the clip you saw at the Human Rights Watch Festival, [that person’s] argument was she was the single daughter of her family, so because of the one child policy, she was able to enjoy the family’s entire focus and resources that allowed her to come study in the U.S. and if she had another sibling, she might not have that benefit. And I felt really sad when I hear arguments like that because China is a patriarchal society where they value males way more than they value females, so when people look at the policy and think it helped them improve their status, especially women, and that was the reason to support the policy, it just shows how passive they are instead of focusing on the problem and fighting for real equality. If that’s the reason they believe a policy like the one-child policy should exist, then it’s tragic and alarming to think what other policies people would be willing to support in order to gain more resources. It easily could [extend to] eliminating a race or a group of people so [the individual] can enjoy more and they’re not that far from going towards that direction.

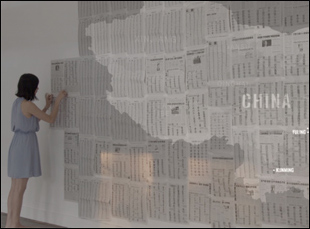

A major theme of the film is seeing this history being erased in real time as the propaganda promoting the one child policy is literally being painted over. What’s it like simply being there to collect evidence?

One of the reasons that I love what I do as a documentary filmmaker is the work itself is a witness of the history and I do hope all the work can survive the time and survive the propaganda. Many years from now people who want to discover the truth of the history, they can still find it and understand it.

“One Child Nation” is now streaming on Amazon Prime here.