When Michael Dweck and Gregory Kershaw set their sights on a part of the world that they’d like to settle into for one of their films, they’re always looking for something a little extra. Which is why when the duo behind “The Last Race” and “The Truffle Hunters” learned as they were looking into the gaucho community in Argentina, there was a type of rancher that was considered even a little more deeply entrenched in the land and the way of life.

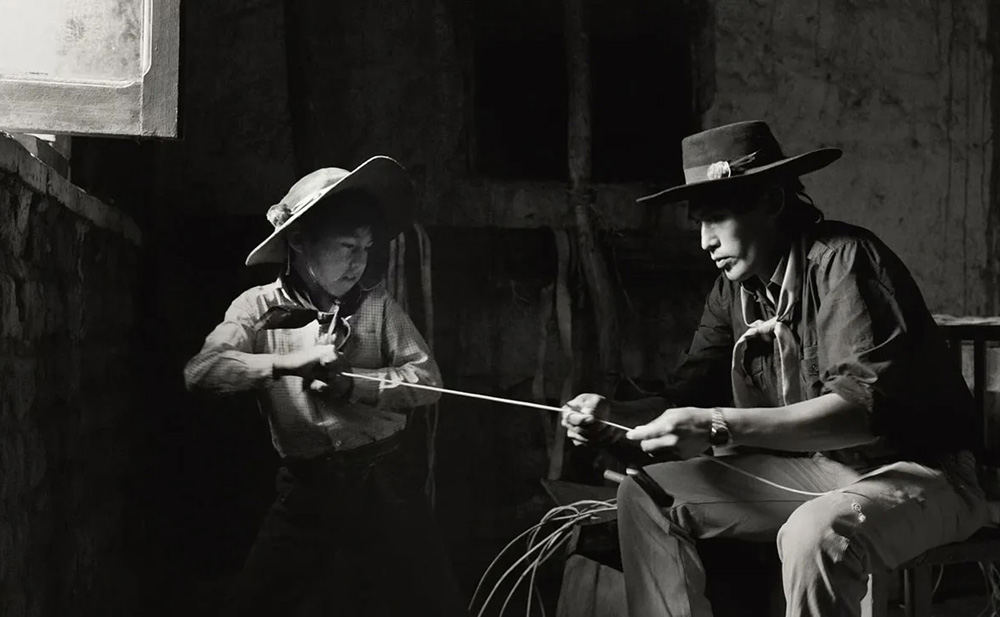

“To be gaucho gaucho, you have to stick to the traditions, you have to make your own clothing, you have to be independent, you don’t work for anybody, you have your own cattle, you grow your own food, you sing the traditional songs, you keep the customs and the spirituality alive,” said Dweck. “There’s a lot going into what a gaucho gaucho is.”

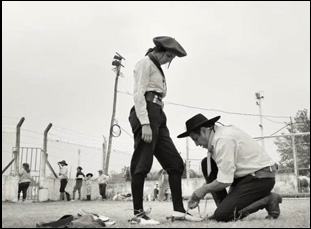

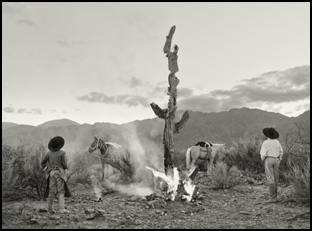

Naturally, that’s why “Gaucho Gaucho” packs such a punch when Dweck and Kershaw in their customary fashion place audiences squarely in their experience, riding into Calachaqui Valley with a trio of cowboys on horses who seem as if they haven’t broken their stride for centuries. Still, the area where they live is a generally a quiet one with enough electricity to power a local radio station, but used sparingly for other reasons when customs from farming to empanada preparation haven’t changed over generations and people still head to the local rodeo for entertainment. A rougher road has built character in the region where the filmmakers find plenty of them as they cover a spectrum of life from community elders whose histories have become the stuff of legend in the region, so much so that the younger members of the community from a pair of boys that roam the area in duds from a Sergio Leone western to a teenage girl who is desperate to get in the rodeo and tame wild horses look forward to carrying on their family legacy while carving out an identity of their own.

After premiering at Sundance earlier this year, “Gaucho Gaucho” is about to turn every venue it plays into a home on the range as a place to bask in its gentle spirit and with the film helping to launch the new documentary on-demand service Jolt where it is now available, Dweck and Kershaw are barnstorming the U.S. on a theatrical tour with stops this week in New York, San Francisco and Los Angeles. Graciously, they took the time to talk about what drew them to Argentina for their latest, how they could use a wide frame to tell multiple stories within them and how each of their subjects had a signature sound.

Michael Dweck: We’ve both spent quite a bit of time in Latin America. Gregory was working on a bunch of films there, and I started to travel there as well in the early ’90s. I met my wife, who’s Argentine, and made a bunch of trips there over the years. But Gregory and I talked about this story for a long time, just waiting for the right time to start filming it and when we set our sights on going down there to get to [really] know a community, we looked at different communities around Argentina and we tried to find one that was sticking to these traditions [of the gaucho gaucho] and in a place that was really cinematic. We ended up in Northwest Argentina, in the south of the region, which turned out to be pretty remote, but at the same time quite beautiful. That’s where we ended up spending two years, embedding ourselves in this community.

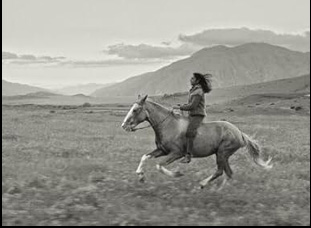

Gregory Kershaw: It’s a stunning region and it’s a culture that’s so beautiful. There’s so much pride that gauchos take in the way they dress, the way they look while they’re riding a horse. It’s otherworldly when you’re there with the combination of the landscape and the gauchos on their horses also have gato montes, which are these big leather fans that come out to protect their legs and when they’re riding their horse with these, it almost looks like wings. You can see that in the film – it looks like they’re flying. So when you’re there, you feel like you’ve stepped into a heightened reality.

Then the process of meeting people takes a while. There’s a few we met early on — Lalo, with the grey beard, and the Choque family, that deals with the water issues — but some of the other people that we filmed with, we didn’t really meet them until we’d already been filming a year. It’s a very slow, gradual process of getting to know the community and sharing meals with them and one person introduces you to another person. But we kept asking the question, “Who’s Gaucho Gaucho? Where are the real Gauchos? And they led us in lots of really interesting directions. One of the names that kept coming up when we asked that question was, “Taty Gonza, he is the most Gaucho Gaucho you will ever find.” So we went down to visit him in Chihuahua and he had his family with him. He brought his daughter, Guadalupe Gonza, Guada in the film, and he pointed to her and said, “She’s really the person you want to be filming. It’s her story. She’s carrying the torch.” So he pushed us in her direction and she ends up being in a lot of ways the story that holds it all together in a lot of ways.

Then in some of the other characters, like Wally, who is dealing with the issue with condors, he lives on a mountain that’s on top of another mountain, so you drive up this mountain, and you think you’re there, and then you ask the people in the town, like, “Where’s Wally?” They’re like, “You’ve got to go up to the other mountain.” But the moment we met him, he started talking about how the world had fallen into chaos and things that had never happened before were now happening, like condors attacking cows and that was so intriguing. It’s such a unique and specific thing, and also very cinematic. And he’s dealing with it on a day-to-day basis, so that quickly became the story that we focused in on with him.

Michael Dweck: They are farmers and they do have rituals. There are also a lot of unexpected surprises that for us as filmmakers, we have to go with, like when we found out that one of their cows gave birth, and they were up all night for seven hours because the birth was complicated. Those things get in the way of rituals. But in general, they eat the meals at the same time and a lot of the conversations we heard a lot, and that’s why the way we film [where] the camera is static, and the shots are very long and there’s no cutting within the shot, so it gives you a chance to really observe these moments and to take your time. [We encourage you] to start start looking around the room, or when we’re in the forest, notice the trees, look at the brush, study the cactus, study what they’re wearing, listen to what they’re saying.

Our style of filmmaking is very deliberate in that way, so when you’re seeing somebody sitting at a table having a discussion, maybe we film that same table over two years five or six times and what you’re seeing is two minutes out of a two-hour conversation that we film a lot of times. We don’t go into these films with a story ever. We just dive in. We have a hunch that it’s an interesting community we enjoy being in, and we hope that stories come out of our time spent there. It took two years to make this film, [which is] the shortest of any film we’ve made so far, but typically, it takes months and months and sometimes a year for [the community] to really get used to us, to trust us, and because they’re very busy, they’re not paying attention to us. We’re trying to just not get in the way.

You’ve always employed a wide frame, but it was particularly exciting here how you use it to show both ends of a conversation or the amount of different activities going on at any one time, like the first moment with the grill where there’s dancing on the other side of the frame. What was it like figuring out the right compositional fit?

Gregory Kershaw: Everything we do doesn’t really come through a logical process. It’s all really intuitive. After our first trip in this landscape, we knew we wanted to film it in a wide screen to capture the vastness. Also the wide screen evokes the idea of the Western and the feeling of a John Ford film. As we started exploring that as we were shooting, we did realize this ability to tell two stories at the same time and the focus is so big that you can have multiple points of interest in a frame, which you really can’t do with an aspect ratio that is not as wide. It became really fun to explore moments exactly like the moment that at the asada, where they’re sharpening the knife and people dancing on one side and other people are popping open a beer bottle and it’s all happening in a single frame.

But the actual process of setting up any frame while we’re shooting, it’s always Michael and I working together to figure out how we can reflect what we’re feeling and looking for that frame that will bring an audience into that moment with us. We’ll be searching [for it] and we’ll shoot sometimes just one shot a day and that day is spent searching for the moment to film and the right way to film it. But when it comes together, we’ve been working together long enough now that we don’t even need to talk about it. We just know and we look at each other and we know we have a scene. At this point too, we can know when it’s a scene that’s going to be in the film or not, because it just speaks to you and it’s magic.

Gregory Kershaw: It was an evolution from our previous films. We first started putting cameras on the race cars that we were filming for “The Last Race,” which led to the dog cam on “The Truffle Hunters” where we had little GoPros on the heads of the truffle hunting dogs to bring you into the dog’s perspective because they were a character. In “Gaucho Gaucho” with the horse, we really wanted the audience to feel the intensity of these jineteadas [the matadors], because it’s really dangerous what they do. They don’t wear helmets, and they don’t wear any protection on their bodies, and every jineteada that we would go to, we would see these rodeo riders being dragged off by an ambulance. That was every single event. It’s a really, really dangerous sport. So we wanted to put the audience in that position to feel the threat that the humans face when they’re getting on these horses and the visceral intensity. So we mounted a little GoPro on the head of one of these horses, and then working with Stephen Urata, our sound designer, [we had] to figure out the sounds that pulled you into the intensity of that moment, which is what Guada is going to face in the film.

The sound is also always an extraordinary part of your films and something I’ve heard about this that I was unaware of previously, you actually attach certain sound profiles to the specific subjects. Are those associations made pretty early on?

Michael Dweck: With Lalo, the character with the white beard, you see he’s in his early eighties and lives on a farm where he has a squeaky windmill. And f you listen, you’ll hear like a squeaky, rusty windmill from “The Good, Bad and the Ugly.” It’s a very similar windmill sound you hear from the opening scene, so that’s the profile we attach to him throughout the film. Also, when Lalo is also with a healer and the healer is brushing the card, we take the audience from the outside into his mind. You hear the brush of the card on the fabric, and then when we take you inside, it becomes this dreamlike sequence of sound where you feel like he’s how he’s been healed because he wants to be younger. He goes to the healer and says, “Look, make me young again. I’m 81 and I’m having trouble walking.” We did something similar in “The Truffle Hunters” when it came to the [person we call] the judge when he was savoring the truffles after a dog had been poisoned. You’ll be savoring it, and the more he eats, all of a sudden the opera goes from the subjective world to the objective world and vice versa throughout this experience.

We don’t want it to be very obvious what we’re doing, but we think that’s an added layer and sometimes a bit of a surprise. One of the scenes with the Chilke family where they’re praying for rain, we sat with the sound designer Stephen Urata, and we said to him, “What’s the sound of God? What is the sound of the spirit that they’re conjuring up?” Because they have an indigenous spirituality, but also Christian beliefs, and they’re literally praying throughout the film for it to rain. So what we did was we played with these high frequency sounds that you could hear in the theater, but it gets into your gut. It really just makes you feel a bit anxious when those scenes happen. So we experiment a lot with sound design.

“Gaucho Gaucho” is now available to watch on demand on Jolt. It will have special theatrical screenings with the filmmakers in person in New York on December 3rd at the Quad Cinema in Los Angeles on December 5th at the Laemmle Glendale and in San Francisco on December 8th at the Roxie Theater.