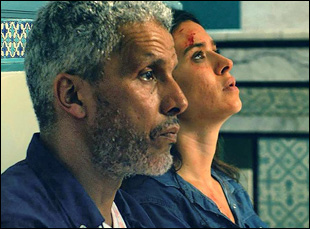

Aziz (Youssef Khemiri) isn’t anywhere near driving age yet when “A Son” begins, but that isn’t about to stop his father Fares (Sami Bouajila) from letting him have a little fun behind the wheel, cruising around the wide open roads in Tunisia. The family, including mother Meriem (Najla Ben Youssef), are en route to a celebration for Fares’ promotion at work, putting him in charge of an entire region as a human resources director, but with growing unrest in nearby Libya where an overthrow of Muammar Gaddafi’s dictatorship is underway in the fall of 2011, no corner of the Arab world appears to be untouched by the revolution that would be come to be known as the Arab Spring and though Fares and Meriem would seem to be able to go about their daily lives in peace, with Aziz outfitted in no less than a Superman tee, yet that all changes with a bullet through the window of their car.

“A Son,” which earned a Best Actor prize for Bouajila at the Venice Film Festival in 2019 when it premiered just before the pandemic complicated its path to the rest of the world, shows the family thrown wildly off the road by the violence that is increasingly creeping into Tunis with a stray bullet puncturing Aziz in the stomach, leading Fares and Meriem to desperate measures to save him. Navigating the medical system is fraught enough for the concerned parents, but writer/director Mehdi Barsaoui throws a particularly cruel curveball in when Aziz’s tests reveal that he may not be related to them in the way they thought. As Aziz is under intensive care, Fares and Meriem grapple with whether the revelation changes their relationship to their son, and beyond a compelling family drama, Barsaoui finds a provocative way by extension to examine people’s connection to the country they’re born into even if they are feeling increasingly disconnected to what’s unfolding there.

With “A Son” finally making its way to America with a premiere run this week at the Film Forum in New York before traveling across the country, Barsaoui recently spoke about how he put together his fierce and thoughtful feature debut, tying the landscape to the narrative and working with his cast for a film that could feel as true to the environment and themselves as possible.

It’s a simple question, but also complicated, and I cannot say that the film is autobiographical because I am the biological son of my mother and my father, but I grew up in a recomposed family. My mother had another marriage and my father too and I have some other brothers and other sisters and since my childhood, I’ve always questioned what is a family? Is it a genetic bond? Is it a blood sequence that can unite some people? And growing up in Tunisia and after the Arab Spring and the revolution, I was questioning the meaning of being a father in Tunisia, or being a couple, being a mother or being a child.

I started writing the script in 2014 and the idea was a family being stuck in a no man’s land and with all that’s happening in Libya, [it was a question of] how will they deal with this mess? I was very interested in that because I’m talking about Tunisia, a country, but I’m telling also the story of a [specific] Arab area in Libya in chaos and I was immediately interested in how the political scene can interfere in a very intimate story of a family. The structure of the film [itself] is very simple, very easy – it’s a father and a mother trying to save the life of their son, but there is also a problem on the border, there is this chaos in another country, a terroristic attack here in Tunisia and it’s all a mess, so all these questions came up with this idea of the film – what does it mean to have a son here in Tunisia in 2011. All these questions made the film.

Emotions would seem to be attached to the geography in terms of how distant the family becomes from one another. How did that contribute to your ideas about this?

The idea of the film is based on this struggling of this family, going from Tunis, the capital to the north to the South to Tataouine, discovering the region for some professional reasons for the father and this idea of family in the beginning of the film, they look pretty good and pretty rich, they have a baby boy with a perfect hair cut and we discover with them the reality of the country. They are really disconnected because they are living in Tunis, and being there, they are losing all their references because everything is different from the capital in the south, so it’s a way for me also to confront my characters [with] the reality of the region with the Arab Spring and all that’s happening in Libya because Libya can seem very far, but it’s very close to us.

With the chaos there in Libya, it’s also a way for me to talk about what’s happening here in our country and also showing that we Tunisians can be so, so different [from one another]. There is for sure, one country, but there are a lot of Tunisians and it’s about the differences between us and how we can struggle. I often said that the film is a journey to the truth. It’s also for the country, it’s a journey to discover our country.

Sami Bouajila is Tunisian, but he grew up in France, and he’s very well-known in Europe and especially in France and maybe one year before the shooting, I saw a very famous Tunisian movie called “Le Silence du Palais,” directed by [the late] Moufida Tlatli, who left us a year ago and I saw Sami and said, “Why don’t we see Sami in some Tunisian films?” Then my producers contacted him and he read the script and he fell immediately in love with this character and the spirit of the film. Najla [Ben Abdallah] was a little bit different because Najla is a TV star and she’s very famous here. She can not [walk] 10 meters in the street without being stopped by fans, but in cinema, she has a [relatively] small career, so it was a little bit complicated to trust her in the beginning. [It took] four or five tests before she convinced me, but she was totally involved in the film and she loved her character.

And we shot the film over six weeks, not a lot [of time], so I really needed to arrive on set and know exactly what I have to do, and for that reason, it was very important for me to make a one-month-and-a-half of rehearsals with the main couple, but also with the Youssef [Khemiri, who plays the son Aziz] and Sami, who was living in France and came to Tunis almost two months before the shooting. We rewrote the dialogue together so it can be very smooth and natural because I really believe that the gaze of the camera really sees when you are not authentic. It’s very important to me. So we rehearsed all of the scenes together and we were looking for the right tone and the right gestures, and [when] we went on the shooting, we knew exactly what we had to do, so I didn’t change a lot from the written scene and the scenes that we see in the film, but I changed a lot in the dialogue with them so they can be very natural [on screen].

Was this a real hospital you were shooting at?

I think you will be surprised, but we shot the hospital scenes in six different sets, so the emergency room is in one place, all the unit of the surgery unit was 500 kilometers away. The doctor’s’ office was on another set and the pediatric place is in a studio, so it was a real mess for our art designer, but I think she really succeeded in giving it coherence and the audience doesn’t see the difference when we moved from one set to another. The hard work was to repaint [everything] the same color, so we don’t see the differences.

It was very important for me and Antoine Héberlé, the cinematographer of the film, since the film is very melodramatic, [that] we didn’t put another level of pathos with all this aesthetic of the drama. We really wanted some naturalistic, realistic gaze on this story and on these characters, so all this is filmed on a handheld camera and during the beginning of the movie, it’s very luminous. It’s very sunny, and a lot of colors — a lot of green — and it’s a way to describe this perfect family living in a perfect cocoon in a perfect reality in a perfect Tunisia and then moving to the south and seeing all this change [with the] color changing with all the colors of the desert. It was important for us to not use [artificial] light when we were shooting the external scenes. I really wanted to be free with the camera and the actors in all this desert. The light is already beautiful and fantastic, so we didn’t need to put another and to respect nature.

When this is your first feature, was it any different for you?

Yes, it was completely different. It was a big responsibility for us and with all the people that believed in me – my producers, my financiers and all my team, all the actors, I’m very grateful because making the first feature in Tunisia in the south of the mediterranean area, it’s very difficult because it costs a lot and I hope that they will believe in me another time on my future projects. I think that we succeeded, even if I really can’t see the film because I see all of the mess I did and all the things that I want to change and now it’s too late. [laughs] Here in Tunisia it was a real success because the film stayed in the theaters during three weeks, [which was] huge for local film and also, the film went to a lot of festivals and won a lot of prizes and awards. I’m happy to see that there is some universal message that other people around the globe — I went to India and to Australia. For a Tunisian film, for a very small film to be released in Australia and New Zealand, it was completely amazing. I went to all the regions here to present it and talk about it and it was very professional, but also a very beautiful human experience. But it was completely different from my previous works and I continue to learn.

“A Son” opens on December 10th in New York at Film Forum and December 17th in Los Angeles at the Laemmle Royal.