When Max Eriksson began to sift through the hours and hours of skate tricks that Ali Boulala had been filmed over the years, the director hadn’t been interested as much in how the skateboarder could seemingly defy gravity, but the moments before and after the trick where his feet were firmly planted on earth.

“When I got tapes and started rolling footage, I found that I could see a lot of personality shine through from that footage that you normally don’t see in a skate video,” recalls Eriksson. “You normally see this trick that they land and then you go onto the next and the next and it’s a high-paced 2-3 minutes, but I wanted to slow it down, have a look at all the times they tried the trick, over and over and you see the frustration build in them and you see them going for it one more time to maybe make it.”

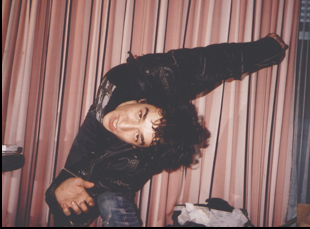

After Boulala was gravely injured in a motorcycle accident in 2007 that claimed the life of his fellow skateboarder Shane Cross, that frustration became a part of his everyday life, not only inhibiting his mobility but taking away large parts of his memory that he continually struggles to reclaim. In making the deeply moving “The Scars of Ali Boulala,” Eriksson isn’t so much telling the story of Boulala’s life as summoning his spirit when someone who was enigmatic to others before the accident becomes a mystery to himself. Once having the prankster energy one might expect of someone who thought nothing of climbing atop a roof of a gas station to pull off a monster jump, Boulala is introduced as being far more subdued these days, with his arrested development that was once a choice now an imposition when he’s unable to skate and lives with the burden of his friend’s death.

As his ex-wife Amanda says, “I feel like I’ve known four different Alis — it’s crazy to think how many lives he’s had” and Eriksson beautifully captures all the layers of Boulala’s experience, recasting all the antics of a restless young man that were previously caught on camera in a new light when 15 to 20 years on, he and those around him can look at them with a much different perspective. With an ethereal Warren Ellis score and the gentle hand of Eriksson to guide you through, “The Scars of Ali Boulala” lets one feel as if they’re reaching the same heights as its subject once did and brings the calm that comes with him finding inner peace as much as he can. With the film screening this week as part of the Tribeca Film Festival, Eriksson spoke from his home in Stockholm about how he was drawn to make a film about Boulala and the work of reconstructing a past that his main subject couldn’t entirely speak to himself.

I grew up in the street culture, hanging around skate parks and graffiti artists, so I knew who Ali was even though I never skated myself. I had a lot of friends who were skateboarders and they showed me his videos and they were all in awe of Ali. The years passed and I stopped hanging around skate parks and I remember seeing a headline in Sweden saying “Skateboard star in death crash” and I bought the newspaper and read the story and it turned out to be Ali. I was like, “Oh my God, how will he cope with all this?” And then years passed again and I was shooting another documentary and I went into a bar with the guy I was shooting and in that bar was Ali drinking and this film just rushed into my head. I was just like, “Okay, I have to do this film. Now I just need to find a way to get in touch with Ali.” That process took about six months to get somebody to connect me with him to see if he was up for making a film about it and he was really reluctant at the start, but he finally came around.

Knowing all those videos were out there must’ve been helpful — and this is the most prominently I’ve seen an archive credited in a film – did you know where all of it was?

It was very rewarding and a big hassle at the same time. Skateboarders are not known for being very meticulous when keeping track of their old video tapes, so we have been combing the world, trying to find who shot what on what camera and on what format and then finding the original tapes and getting them to us to later digitize. But we had great help and as you said, I credit them at the start of the film because to me, this film would not have been the same without all that archive footage. I was just tired of seeing archival footage being credited at the end of the film. This film is probably made up of 60 percent of that footage and without it, it wouldn’t have been the same, so I wanted to have them on the front row, having the big thanks.

Was there any piece of archival that broke this open for you?

The footage of Ali in the hospital was a big moment that we got. I reached out to the videographer Ewan Bowman and I said, “Okay, I’ve never shown this to anyone. See if you like it and if you can use it, feel free to do so.” When I got that, it just broke the mold. I knew how important that was because in the film and also in Ali’s life, so much of him had been videotaped in one way or another. When you’re skating, even before you become a professional, they were filming each other just for the fun of it, so from 10 years old up until the accident, almost everything with Ali was [on] video, but from the date of the accident, there was no more footage. That became an issue for us to solve in the film and having Ewan filming Ali in the hospital, it’s was an important part of the story because we can continue seeing him. Later on in the film, we also found the wedding tape when he married his ex-wife and that also became an important part of telling the story.

Was he a challenging person to interview, given his memory?

That’s a hard question. Ali is very much Ali. You can’t make him doing anything you want him to do. He has to want it himself, otherwise it’ll never happen and I had to take that into consideration when I was talking with him or when we were shooting. Every time I tried to get him to do something, like “Can you walk down the street and we can film you?” he really didn’t want to do that. [laughs] And when I talked to the old videographers that filmed him, when they came to him and said, “Oh, I found this perfect spot for a skate trick, can you do it?” He was always, “No, I cannot.” So I had to learn to work with Ali and I feel like we definitely found a great way to do that where he felt comfortable and I felt comfortable and we just let the story unfold in its own organic way.

Was there any direction this took you weren’t expecting?

As a documentarian, I really roll with the punches, so I didn’t have too many wants or have-tos when I started filming this and I never have those, but at one point in the film, we break where my voice comes into it [because] I realized since somebody needs to bounce off of Ali when he always goes back to “I don’t remember, I don’t remember.” I can say, “Well, in the footage, I can see you for the first time with him…” and get his reaction to that. That may have been one of those moments that might’ve been a really big one. My editor actually found that and added it to the film and just called me and said, “Hey, I did an experiment” and it was like, “Boom, got it, thank you.”

Most of them are introduced through the meta-layer and I really liked that because I have a hard time with documentaries that pretend not to be documentaries. I have been in the room with these people and I was the one asking questions. My camera people have been there. The sound people have been there. So to try and mask or pretend that we were never there and that this just magically got captured and then got edited into the film is complete bullshit. I believe in being part of the filmmaking. That doesn’t mean I will narrate the film or I will be onscreen, but documentaries are so amazing because somebody has gone there and captured it, so that to me was a way to incorporate that into the story. When Rune [Glifberg] is like, “What’s in my pocket? Oh, it’s the mic.” Perfect. We know we’re in a documentary situation. He’s aware of the camera, I’m aware of the camera.

What was it like to work with Warren Ellis for the score?

It was fantastic. He reached out to us through Ali’s friend Dustin Dollin and he watched a cut and said, “I love this. I would really be happy to work with you on this.” It was just a few weeks, we got the soundtrack, but it was perfect.

What’s it like getting to the finish line now?

We rented a cinema today to watch the final version of the DCP and it was fantastic to sit back and watch the film without a pen and paper, taking notes because we’re done. I [actually] felt, “We’re done” and I would just love to be at the actual premiere at Tribeca but since the pandemic, I’m not allowed to travel to the States, so I’m super-frustrated. I told my wife yesterday, it feels like I’m graduating, but I’m not allowed at my own graduation.

I’m so sorry about that, but I hope you feel the love that I know is going to be out there for this…

Yeah, I’m happy the film is going to start its own life now. Ali has seen it. We showed it to him a few weeks ago and he asked me a while back, “Will I like the film?” And I said, “No, you will never like any film about yourself. You’re too self-conscious about it.” And when the film was done in the cinema and the lights came on, it was dead silent. I thought, “Oh, this is not good.” But the first thing he said was, “Hmm, I don’t hate it.” And I was like, “Yessss!” That’s the best thing I could ask for.

“The Scars of Ali Boulala” is available to stream through the Tribeca Film Festival through June 23rd.