Matthew Perniciaro was on cloud nine upon his return at Sundance last year, riding high on a wave of acclaim for the trio of films that his production company Bow and Arrow had backed — “The Truffle Hunters,” “Disclosure” and “The Fight,” ready to dive back into his most ambitious project to date as a director, the five-part docuseries “Moment of Truth: The Killing of James Jordan.” While the majority of filming had been completed and one of the five episodes had been edited, the filmmaker was quickly brought back to earth when the entire post-production process had to be reconceived in the wake of the coronavirus.

“The following week, we shut our offices down because we realized we needed to work virtually for everyone’s safety from that point on, so the majority of this series was actually created and edited in a virtual environment, which was a completely new process for me,” recalls Perniciaro. “We had planned to go back to North Carolina and film more and Cliff Baumgartner, one of the cinematographers, I would call him up and say, “Okay, here’s a list of 10 shots that we need” as we were building the story up in the edit,” and he would get me on FaceTime and say, “What do you think about this angle [as he was on location]?” “Okay, great, I love that.” Making something pretty much entirely virtually from the post-production standpoint was a very unique experience.”

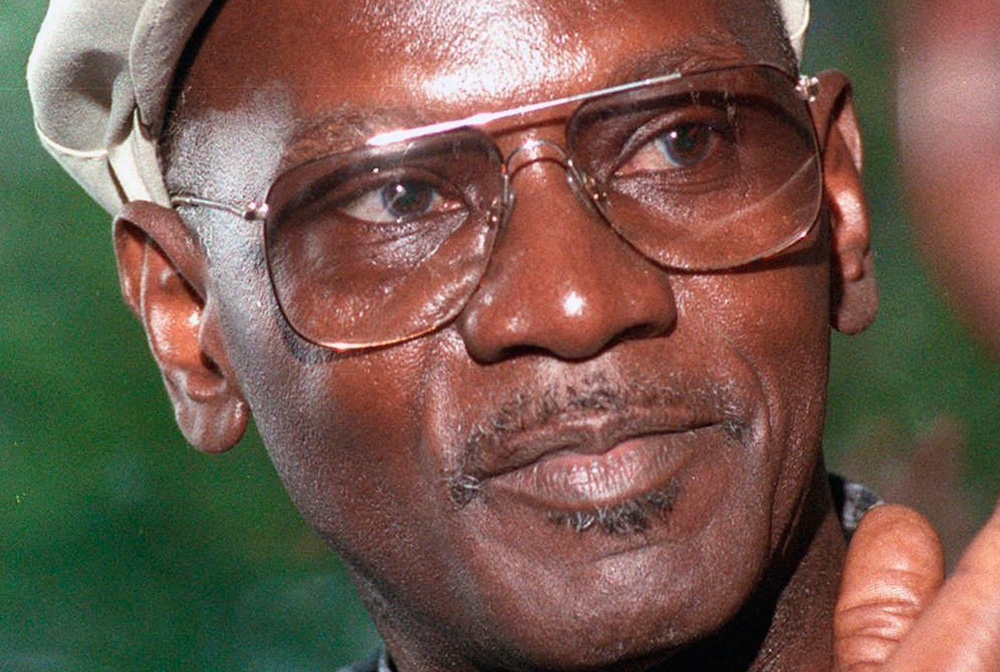

Only a few weeks before its premiere on IMDbTV on April 2nd would Perniciaro and his crew finish up work on the project, but it was fitting that the director would be searching out new angles throughout when looking into the murder of Jordan, a case that drew intense scrutiny when his son was the basketball legend Michael Jordan yet 30 years after the fact remains shrouded in mystery. Although a jury convicted Daniel Green and Larry Demery, two teenagers who were found with Jordan’s belongings including a NBA championship ring and a gold watch, the path to that verdict still brings up plenty of questions, not only in what led Jordan to pull over on the side of the road in Cumberland County where he was thought to be sleeping at the time of his murder, but how Green and Demery were pitted against each other to confess to that crime when it appeared they were responsible for only a burglary after the fact, leading the latter to a plea deal that put the brunt of the blame on Green, a young Black man for whom plenty of assumptions could be made by those looking to convict.

“Moment of Truth” upends many of them as it heads to the Lumberton Correctional Institute for an interview with Green, who might expect to spend the rest of his days there if not for the ongoing work of Christine Mumma at the North Carolina Center on Actual Innocence to appeal. While doubt is cast on this specific case, Perniciaro comes to question the entire system of justice in Robeson County where the trial unfolded, just a short time removed from its police department being investigated for rampant corruption — only after being taken hostage as a result of outrage in the Native American community for the shooting of an unarmed man at the hands of the sheriff’s son — and with court proceedings largely taking place out of the public eye after the spectacle of the O.J. Simpson case. Three decades on, “Moment of Truth” brings as complete a perspective as there could be with both the benefit of time and, working with the local news station WRAL in Raleigh, the impressive collection of footage and people to interview that Perniciaro pulls together.

With the docuseries now streaming, the filmmaker spoke about how growing up in North Carolina gave him a unique way into the story, the opportunities that opened up with letting the narrative take the shape it wanted in individual episodes and vividly recreating a trial in which no cameras were allowed into the courtroom.

WRAL is one of the largest news network in North Carolina, and they had an amazing amount of archival footage about this case, most of which no one’s ever seen before and a lot of which has not been aired in 25 years. It mostly only aired on the nightly news once in North Carolina. Jimmy Goodmon, [the president of Capitol Broadcasting, the parent company of WRAL], and I grew up together, and he actually originated the concept for this show. We’ve been friends for a very long time, and he reached out to me. An amazing team of Emmy Award-winning journalists were already working on stories about this in advance of the 25th anniversary of the murder that could’ve been designed originally for their local network, but [Jimmy] called me and said, “I’m looking at just how much archival we have and I think there’s something bigger here.” So we started talking about it in 2018 and then in 2019, I formally joined the team with this amazing group of journalists and Clay Johnson, who co-directed the first two episodes with me and we wrote the series together. It was a true team effort. When you partner with a news organization, a lot of times people view that as “Oh, they’re just providing materials for archive,” but this case, it was a real true co-production between my company and Capital Broadcasting.

It seems like the North Carolina Center on Actual Innocence must’ve been a great resource as well when they were collecting material for the Daniel Green appeal. Were they like a partner as well?

A lot of the information as it relates to the evidence mostly came to be like FOIA requests and the state allowing us to view and film pieces of evidence that they had not shared previously. But shortly before we started this process, Chris Mumma at the North Carolina Center for Actual Innocence had taken on Daniel’s case and knowing that we had this kind of present-day, immediate story playing out in real time, we knew that would give a different dimension to the story we were telling and Chris was uncovering new pieces of information in her investigation to present Daniel’s case to the court. We knew that this was a period of time that was going to be very unique and reframe the narrative that had been told for decades about this case.

The series feels exactly the right length, which has rarely been the case with a lot of these recent documentaries and it seems like that may be because each episode doesn’t have a uniform length. Did you know what kind of shape this would take from the start?

As a filmmaker and a producer, I’ve always been story-first — you want to present the story in a manner that’s the strongest way to tell that story for an audience. When we started working with IMDB TV and Amazon Studios on this project and they said, “Hey, look, with streaming, it’s not a traditional broadcast, so you don’t have to worry about every episode being exactly the same length. You don’t have to worry about all of the typical rules that we think about with broadcast series.” When we started, we didn’t know if it was going to be a feature or a series. But we figured out pretty early on that a series felt more appropriate and originally we were thinking, “Ok, if you do it as a series, you’re going to have one-hour episodes. That’s the standard.” But then when we started working with IMDB TV, they said, “No, you should break it up however you feel the best storytelling will come across,” so that was a revelation. I think that’s going to be a very exciting way for filmmakers to start working in the streaming world.

We knew very early on in structuring the story that telling the history of Robison County was going to be very important because I felt that audiences needed to know what the atmosphere was in that county where both the crime took place, and they needed to have that information before the trial takes place because it’ll inform your opinion of all the information that you’re hearing. There’s a history of questionable practices at the hand of law enforcement in this county, so it was important for audiences to have that understanding of the history there before we get to the trial, and a lot of people at first are like, “Whoa, you’re really stepping away from this story. You’re transporting back in time about 10 years and then playing out a series of events over that decade until we get back to this trial.” But we felt it was very important to experience what this world looked like at that time where these young men were raised and grew up. And then from there, we really wanted to play the final three episodes like a trial – the prosecution’s narrative, which was the public narrative, comes first and then in episode four, you’re hearing Daniel’s version of the events. Daniel didn’t testify at trial, so he’s never really been able to tell his story in full to a mass public audience, so we felt that was really important for audiences to have a full understanding on both sides of the story, which hadn’t really been told before.

It was really fascinating because we had the trial transcript. That was the only thing we had at first and it was over 8000 pages long. As we were reading through it, there were pieces of information and statements made that were part of the court record that were shocking. This trial is very much a rollercoaster and you’re hearing pieces of evidence or statements being made and accepted as evidence in the court record — they’re opinions and that really isn’t allowed in our legal system currently. A lot about what can be said and accepted as evidence and entered into the court record has been clarified over the past 30 years, but at the time, you’re seeing a lot of inconsistencies during the trial. So when we went to the courts and said we want to get the audio recordings, those audio recordings were in the physical tape format as they were recorded in 1996 when Daniel Green’s trial took place, so if you weren’t sitting in the Robison County Courtroom during those days of the trial, nobody’s ever heard this audio before. That was really exciting [because] we wanted to put people in that courtroom, and because there weren’t cameras, we used photo visual effects, taking all the individuals that were involved in the trial – the lawyers, obviously Daniel Green and Larry Demery, and Judge Weeks, and we rebuilt it all in a virtual courtroom, using still photos. It was a process that we were really excited about, how to bring something to life visually where visuals didn’t exist.

Was there anything that changed your ideas of what this could be or changed directions on you?

Growing up in North Carolina, this was a case that was reported on every day from the moment the crime occurred really up through the trial locally, but I was not aware before starting this process that it was not reported on nationally nearly as much. So to really look at all this archival, I remembered some of these news reports, watching them at 13 years old, but also I think a lot of times we think 1993 is not that long ago and when you really start looking back on it, you realize how much time has passed and how much different the world looked then. When Johnson Britt, the district attorney for Robison County says, this was to his knowledge the first case where cell phone records were ever used as evidence in North Carolina, now we think of court cases and cell phone evidence is usually a key factor in most of these cases in identifying where people were at any specific time, so it just does remind you how long ago it was.

It was interesting because Dan had come from the Midwest and goes to North Carolina and starts discovering that there was so much more in North Carolina than had ever been reported before, so we wanted to show audiences that existed. For me, coming from North Carolina, I just had this very deep connection to this story. I’m a kid of the ‘80s and ‘90s, and if you were into sports, Michael Jordan was maybe the biggest icon on the planet for a kid growing up during that period of time. And this was shocking – that this happened in our home state where he was from and it was one of those moments like the Challenger explosion. It’s as big as that moment was for our generation, one of those handful of moments that just stays with you.

What I realized is, from a very young age, there as something that just never fully added up. There were always these questions about it and in many ways, that led people to go into these false narratives and conspiracy theories that have clouded the case for so many decades. The minute you start looking at the facts and the evidence, you realize that those are all false — and we obviously looked at everything because we wanted a complete and definitive telling of this story — but there was these elements that just didn’t make sense and even at a young age, that stuck with me, so when Jimmy and I had that first conversation, I immediately started thinking back to that time, going “You know what? No one ever really did figure out this complete story. No one else really did tell this in a definitive way where all sides were being looked at, so as a filmmaker, that’s a challenge, but it’s a very exciting challenge to try and bring that to life.

“Moment of Truth” is now streaming on IMDb TV.