There was a time when, as recalled in Mark Landsman’s ferociously entertaining new film “Scandalous,” the National Enquirer was intended to be an escape from the real world, sitting on the edge of the supermarket cash register promising gruesome car wrecks, UFO sightings and celebrity gossip that someone buying groceries likely never would encounter in their daily lives. As Tony Brenna, a former reporter for the tabloid, says, Generoso Pope, the prophetic owner of the tabloid, “would prefer to sit in Lantana [Florida where the Enquirer was based] and let the world come to him.” In fact, sixty years after its creation, the Enquirer may not be as widely read from cover to cover as it once was, ceding the gossip game to 24/7 sites to the likes of TMZ, yet may be more influential than ever, if the election of Donald Trump was any indication, still residing in the very best real estate for a print publication in the country and using its prime perch to instigate and inform narratives that the powerful can embrace as truth with no actual foundation in reality.

As Landsman, who interviews numerous Enquirer employees from top to bottom over the years, illustrates in “Scandalous,” the Enquirer’s pernicious influence is hardly new, honing in on a selection of articles where the paper’s unorthodox and often unseemly journalistic practices could shape news cycles with reporting that no one else could get, such as in the O.J. Simpson murder case where a number of the officers involved knew their tips could earn them some extra cash, or by tucking away a juicy tidbit about a major star in return for their cooperation on something far more flattering, contributing to why Bill Cosby’s criminal activities went unreported for 30 years. “Scandalous” hardly leaves out more well-respected outlets for criticism, observing how they began to chase the success the tabloid had in peddling salacious stories for a greater audience share, and as the film picks apart how the Enquirer conducts its business, it becomes fascinating to see how thin the line is between what’s considered unethical behavior and dogged journalism.

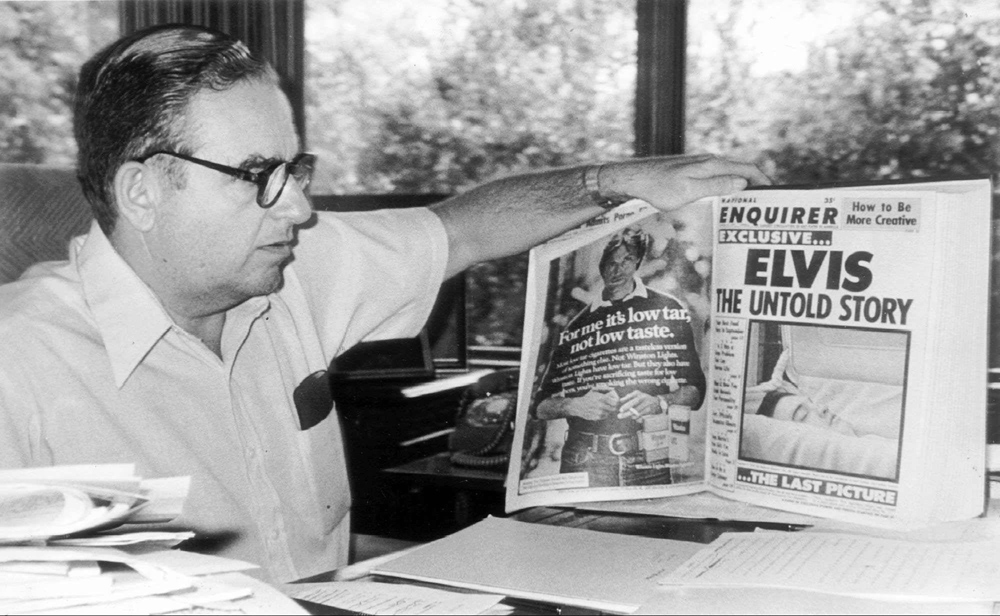

However, “Scandalous” is well aware that its subject isn’t meant for a sober history and replicates the sugar high of seeing an Enquirer cover without feeling as if you’re ingesting empty calories, energetically offering up one wild story after another behind the stories that appeared in print, whether it’s describing the crazy lengths the paper went to get a picture of Elvis Presley in his open casket as he was being laid to rest privately or establishing their relationship with Trump. With the film opening in theaters this week, Landsman was recently in Los Angeles to talk about the challenges of creating a comprehensive history of the tabloid that could grab audiences in the same way and making such a dynamic film out of a story largely comprised of interviews, still photos and reporter’s notebooks.

The timing was freakish in terms of what was going on in the news. Inthe early summer of 2017, a family friend calls and says, “Hey, my parents are in town. Why don’t you come have dinner with us?” And we’re at a Cheesecake Factory in Marina del Rey and her dad Malcolm Balfour starts telling stories about his former career about his earliest days at the National Enquirer. He goes into the crazy tactics of what they did and the more drinks he had, the more he loosened up and he told us about bribes and espionage and checkbook journalism and disguises and recording devices and global travel and bottomless expense accounts. It just started to sound like an “Ocean’s Eleven” movie or like a spy novel, so I thought, “Well, this would be a great film.” This was a few weeks before the first story about the Enquirer broke, which was the Jeffrey Toobin story about the Pecker and Trump relationship, so that’s when we knew something substantial was going on.

I had also been in supermarkets and would get dizzy at all the ridiculous headlines. Like who knew that Hillary Clinton was hooked on narcotics or that she literally at death’s door? The blatant propaganda that was in your face when you went to buy your cereal was shocking and then [there’s] the door that [Malcolm] was opening to me, because he said, “Listen, I’ll introduce you to my friends. We’re all old reporters from the Enquirer and maybe somebody will talk to you,” so that’s how it got going. My producer Aengus James stepped up and we just started filming and then all the catch and kill stuff started to happen. It was like we were on the beach right before the tsunami.

Putting out interview requests in that type of environment, did it help or did it make people more reticent?

There were two camps…three, actually. The camp of “I’m not going to answer your phone calls. You don’t even exist. You’re dead to me.” And then there was the second camp, which was “We’d be so interested in talking to you, but can’t because of fear of reprisal and NDAs” — and in that subset, there were current AMI employees and David Pecker and Dylan Howard, who we invited several times we kept inviting to be a part of the film and they just ultimately said no. And then there’s this entire realm of former legendary Enquirer reporters from the most formative days to very close to the present who were not beholden to NDAs and were actually fascinated with what we doing. No one had ever asked them to tell their story before, and they’re often the target of stories and it’s easy to throw shit and them and denigrate, but what you realize is these are human beings who made choices, like [how] some people choose to join the Special Ops or some people choose to overthrow third world governments. Some people choose to become a tabloid reporter.

The work these people do is almost baroque in nature, so myself, my cinematographer Michael Marius Pessah and my producer Jennifer Ash Rudick put our heads together and I said, “Look, I want these interviews to reflect the theme of the film, which is the Enquirer was always over the top. It was always sensational.” So we made a decision that we wanted to shoot these super-wide frames so that you could really see the person situated in these lavish settings and then Jennifer had published a series of beautiful architecture books [based] in New York and Florida, so we had access to all these architectural masterpieces, some of them extraordinary homes and some bars and clubs and places that we thought evoked the tone. Everyone was amenable to us filming there and I tip my hat so much to our cinematographer Michael [who had] this idea of giving [the subjects] a spotlight, almost the way you can’t take your eyes off an Enquirer headline.

The film is built around specific landmark stories in the Enquirer, but they all serve a central narrative that moves forward chronologically and covers different areas of the Enquirer operation through each major article. Did you have to know in advance of the interviews how each story contributed to the larger whole or did that come from the interviews?

How to structure a film that’s covering nearly six decades of Enquirer history and larger pop cultural history was the fundamental question and for us, it was the paper itself that was [the main] character. It was the Frankenstein and as a result of that, we wanted the trajectory to be the origin story into the various significant major beats where the paper morphed into some sort of next iteration of itself and have those events also be a reflection of where American culture was at at that time – politically, sociologically – so that’s why we chose the events that we did. And we omitted other events that were fascinating. Like I really wanted to go into how they hired a one-man submarine to go under Ari Onassis’ yacht to try and affix a sound device to hear [him and Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis] having sex. There was just no place for it. That wasn’t what we were doing.

I couldn’t believe some of the archival that people were willing to share with us. I can honestly say I was shocked that somebody would willingly hand me a file stamped “Killed By Story Control” – it was on Bill Cosby – and allow me to have that for a documentary. That was extraordinary and I thought it was almost like people really wanted to get the truth out but because of their positions at a paper for so many years maybe thought they’d never have the opportunity to do that or maybe they just didn’t understand that something they had in their possession actually reveals so much about where we’re at right now. I think it was more of the latter [because] the classic line was “We don’t have much, but you can check it out.” Of course, you get notes from the transcript of a reporter who was stalking Bob Hope or Bill Cosby back in Vegas in the early ‘80s when he was keeping a showgirl there, and all of these incredible stories were documented with legitimate artifacts from the Enquirer days. Being able to have those things come to life as part of the tapestry, that’s great.

You bring those artifacts to life as well in a dynamic way through the use of graphics. Was it interesting to create action for a film where you’re often limited to using photos or notes?

Yeah, we always wanted archive to be a living and breathing thing and not have it be something that felt derivative of every other archival usage in documentary. I’m a huge fan of Brett Morgan and I’ve always felt he’s been at the forefront of taking archival and stretching it and doing some incredible things with it from the days of “Kid Stays in the Picture,” so taking that as a springboard, I was very fortunate to work with the artists at mindbomb films. They really were excited to push the envelope graphically with what we could do and have fun with the storytelling, and it was the same with the archival, where we wanted to treat it in a way that feels like a character.

With the “60 Minutes” profile of Generoso Pope, you’re able to get in the building during the heyday. Was it difficult to access that footage?

The “60 Minutes” footage was a goldmine, right? But there were very few cameras that were allowed into the Enquirer in their heyday in the ‘70s. Pope was not a fan of just opening up the office and letting anyone come in. However, I worked with an incredible archival producer named Aileen Silverstone on this – she had worked on “Lorena” with Jordan Peele. She’s supernaturally gifted with archive and she just knows where all the bodies are buried, so in addition to that great Mike Wallace footage of the Lantana office, there was some local Florida footage from the ‘70s that existed in the Wolfson Archive of Pope in his office looking through different files and all these great images of the gardens and life around the Enquirer that we were able to draw from and hopefully make it come to life for people.

Precisely. That was hit or miss. If we had just told the story from the perspective of the Enquirer reporters, it would be a vacuum and a viewer, particularly if you didn’t grow up in that era, would have no understanding of what the rest of the world was thinking at that time, what news looked like or frankly what it meant to have ethics in journalism at that time, so the opportunity to work with some of the leaders of that in terms of American journalism [such as] Carl Bernstein, Ken Auletta from the New Yorker, Maggie Haberman, Keith Kelly from the New York Post, all avid practitioners and watchers of journalism in the past 50 years, was really important. We didn’t want to be a finger-wagging thing like “those kids [at the Enquirer],” but we wanted to understand that this way of practicing journalism by the Enquirer was not unchecked and its impact was felt. It was significant.

What’s it like to be making something that’s a history of a publication meant to stand the test of time, but arriving at a particularly timely moment in its history?

We had to make a decision within the first two months of filming not to chase the news cycle because it was literally breaking news every day. First, it was the catch and kill stuff, then it was Michael Cohen’s office getting raided and then Cohen is going to testify and then Pecker and AMI are getting immunity and it was just like this house of cards that kept tumbling. But we were just like, “You know what? This is the story of the evolution and the impact of this paper. This is not the story of this particular moment in time.” It’s about connecting the dots if we can and hopefully capturing something like a time capsule so that 20 years from now, when we look back on this moment and go, “How the hell did we get here?” Maybe this will shed a little bit of light on it. We were not interested in being the answers. We’re interested in being the question, which I think is ideally what a documentary can do. Hopefully, this one is going to agitate and get people to ask a lot more questions.

“Scandalous” opens on November 15th in limited release, including Los Angeles at the Laemmle Royal and New York at the Quad Cinema. A full schedule of cities and dates is here.