One of the unexpectedly beautiful side effects of the considerable amount of time it took to make “Lenny Cooke” is the way the image quality changes from the time Adam Shopkorn first picked up a consumer-grade DV camera in 2001 to begin filming the titular basketball wunderkind to when it ends nearly a decade later with Cooke barely resembling the baller he once was, surpassed by LeBron James and Carmelo Anthony as prep school sensations and living away from the spotlight in Virginia, captured on a high-def camera by Shopkorn’s childhood friends and “The Pleasure of Being Robbed” filmmakers Josh and Bennie Safdie.

While that brief description of Cooke’s meteoric career which ended just short of the NBA might suggest the reverse, the image comes into focus at the same rate as Cooke comes into his own, a young man who wasn’t only unequipped to handle the pressure of being the number one high school player in the country but perhaps not even all that interested in the sport, except for what it could provide him with financially.

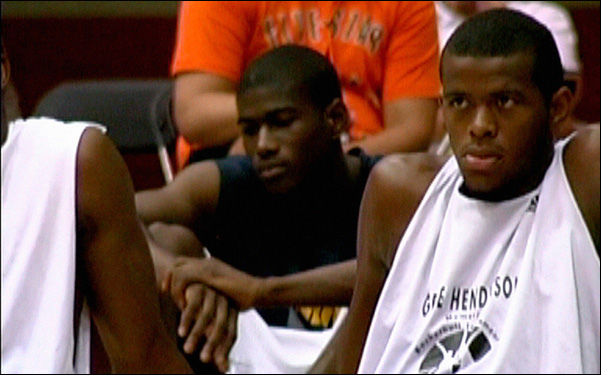

Though Cooke’s story has been told before whether it’s involved the real Cooke was at the center of it or another prep prodigy, beginning in mythic terms and ending as a cautionary tale, it has never had the sheer visceral impact of what Shopkorn and the Safdies have caught in front of their cameras. Filmed in periodic glimpses of his life starting at 17, the movie follows Cooke from basketball training camps where starmakers such as Adidas exec Sonny Vaccaro marvel over his jumper to an adopted home in New Jersey after his mom left for Virginia living the comfortable life of a star player, complete with an entourage, that’s largely predicated on his future potential in the pros. The fragments resemble a perspective that’s still forming, the gaps slowly being filled in by the time he’s 30 and can only watch on TV as his former peers play for NBA championships.

Ironically, Cooke’s commitment to the game was in stark contrast to Shopkorn’s commitment to telling his story, with the latter only putting down his camera in 2005 when he realized he needed to move on and eventually handing his footage over to the Safdie Brothers, who picked up where he left off. The result is an endlessly fascinating portrait of a culture eager to anoint the next big thing before its time and of a man looking to be known for far more than what he was on a basketball court. Shortly after the film’s successful premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival, both the Safdies and Shopkorn, who remained a producer on the film, spoke about how they put it together and what really happened to Lenny Cooke.

How’d you guys get involved?

Josh Safdie: I was a senior in high school and I was really just starting to become obsessed with film and I still loved basketball. I was a diehard Knicks fan. Adam had just gotten out of school and was working on the side on this film. One day, I was over at his house for a BBQ and he said, “Hey, do you want to see some footage of Lenny Cooke?” And I remember he showed us this footage that ended up being in the film down in Virginia. I saw the whole family and I just saw this freakish manchild just dunking on his friends. I don’t think we saw one missed shot. We wanted to work on the film, but …it was his movie.

You fast-forward maybe eight years and we lost touch, but he was always saying there’s a lot of footage of LeBron and then Melo and now these guys are superstars. We really hadn’t seen each other in a while and he and his wife surprised us at a Q & A for “Daddy Longlegs” and he’s like, “By the way, I’d love to show you some of that footage. Do you remember Lenny Cooke?” That’s how the conversation began.

We watched some footage of LeBron, we got past the spectacle of seeing the superstars when they were young and we saw this one clip that’s in the film of this blonde girl in Vegas, sitting on [Lenny’s] lap and just the contradiction of both confusion and wonderment and admiration that this girl had for this guy who had a camera on him was very intriguing to us, so we jumped onboard. Basically, we became psychoanalysts and detectives, trying to figure out who Lenny was and what went wrong. It’s not an easy story to tell because it’s not so simple.

Bennie Safdie:

There’s no easy explanation as to what happened to him and that’s what makes the story special. You have to watch the film and understand where he’s coming from and why he made certain decisions because he was making them by himself.

Adam Shopkorn: And we never got on the phone with 28 general managers and asked them why they never drafted Lenny Cooke. The first time we started working together, the idea of that drove me crazy, but Josh and Bennie were telling me, that’s something you’ll figure out another time. But like [Josh] said, it wasn’t drugs, it wasn’t alcohol. It wasn’t a problem with the law. It wasn’t domestic violence. It wasn’t alcoholism. It was something else.

BS: And it’s just strange because he was the best. There’s a lot of stories of people who had the potential and have made it, but he really was the greatest and it just proves you could have that much talent and still not get there. That’s what makes Lenny’s the ultimate cautionary tale because it was a golden brick path for him to get to the NBA and he still didn’t make it.

What also makes this exceptional is that I think Lenny is probably a better person today than he was back then. We were doing some interviews with Lenny and Lenny’s like “yeah, I was an asshole back then.” The whole experience humbled him to the point where he had to actually grow up and mature whereas the basketball wasn’t letting him do that. There was something about playing basketball that he didn’t like, that was inhibiting his growth as a person. Now, he may not have millions of dollars, but he’s a real human and his soul is pretty pure based on this whole experience.

Adam, when Lenny says near the end of the film that people created an image for him that wasn’t him, did you feel complicit in that, having been around with a camera for as long as you were?

AS: Yeah, I guess. We’ve spoken about that. I felt complicit in the beginning having the cameras on him because it was just an added layer of flash and an added layer of bling.

BS: It was definitely different. The eye that Adam cast on him wasn’t really the same as what everybody else was casting.

AS: Of course, but it’s just inherent in documentary filmmaking. Having the camera on someone as flamboyant as Lenny Cooke, sure, it just added to the spectacle just like the articles written by Harvey Araton and the New York Times added to the spectacle. But I didn’t go to sleep at night thinking I was ultimately damaging or hurting his career. I was an inactive observer.

JS: Everyone was a part of it. By the time Adam got involved, Lenny had already been on the cover of some magazines. Yes, having a camera running around you at the same time is a fault, but at the same time, that’s a test. If you can’t handle it then, you’re not going to be able to handle it ever. Like LeBron says in our movie, “Some people love the attention. Me, I don’t let it go to my head. I just keep my eye on the prize and stay focused.”

BS: Be who you want to be.

JS: In the beginning for a while, I thought the movie was a part of the problem, but I don’t think that’s the case. I mean, that’s life.

AS: New York was a part of the problem. There are always these kids who come from New York who are put up on a pedestal. You have the Post, the Times, the Journal, Newsday, all these critics and New York is still, not so much as it once was, but the mecca of basketball and it’s a tough, tough place to be number one. I always talk about how today, it’s so much more evenly spread out.

There are just as many superstars coming from small-town America as there are from these big, urban metropolises. But 20, 30 years ago, everyone was coming from Detroit or Philadelphia or Chicago or New York. Travis Outlaw, who’s was a great player back then and is in the NBA, he’s from Starkville, Mississippi, so I think the kids from Starkville probably have it a little easier because they’re a little bit harder to get to and they have tighter units. But when you’re in a place like New York and you’re as big and as talented as Lenny, you could get yourself into trouble and he did.

JS: I know a 16-year-old blogger who’s got 30,000 followers and he’s about to drop out of high school because of it. It’s what happens here.

BS: As Josh touched on earlier, Lenny was the future and people knew that, so they latched onto the future before the future happened. That really could do crazy stuff to a kid in high school.

AS: Well, off of what Benny is saying — that ESPN scene when Lenny comes back to Bushwick to show where he grew up, that usually happens after you’re in the NBA, after you have millions of dollars in the bank. You come back to your old neighborhood and you get out of the car and a bunch of kids circle the car and you start signing autographs – that scene actually happened while Lenny was still in high school when he accomplished basically nothing. Was ESPN complicit in that? Sure.

JS: He was also on his own, which is so obvious in the film. You really sense he doesn’t have an anchor, he doesn’t have a home. He’s in Virginia, he’s in New Jersey, he’s in Brooklyn, he’s in Moon Township in Pennsylvania, he’s in Vegas. He doesn’t have a foundation. He doesn’t have a father figure. He doesn’t even really have a mother figure because he left home essentially at 16. LeBron James, you look at his mother, she’s a really fantastic person that was able to create a foundation. Akron, Ohio, it’s like another small town, but it became this very grounded, cement place. Lenny didn’t have that. Lenny was on the streets. Lenny was a roaming island. The NBA knows that. They’re making million dollar investments in these kids. They know all these things, so they’re not going to invest in a kid that is highly individual. Amare Stoudamire is a great example of overcoming that perception because he had a very similar life to Lenny, but he made it …

BS: I think Lenny was too young to have that mindset. He thought, “Oh, I’ve already done all this, I don’t need to do anything else. But to be humbled enough to realize, you know what? I still have to work to do this, those other guys had that.

AS: At the end of the day, Lenny wasn’t hardwired to be a professional athlete. It takes a very, very specific [person]. How many times did you hear in the film: 82 games a season, you’re on the road, you’re never around your family. That shit is hard. The coach who walks with him at Five-Star [Basketball Camp] says, “You’ve got to go to Boston, you’ve got to go to San Antonio, you’ve got to wake up in the morning.” He was telling him all these things and Lenny couldn’t wake up in the morning at 6:30 to run five suicides because he couldn’t get to practice by 8 o’clock. He didn’t care enough about it. He was the best, so he did as he pleased and eventually, it caught up to him. These kids all got better, they got bigger, they got stronger, they got faster and people catch up. Look at Kobe Bryant. Why do you think Kobe Bryant worked so hard? He’s still in the league at 35, still doing what he does because he has that determination to not let people surpass him.

BS: Yeah, but Lenny’s the first person to say, “Listen, I didn’t love playing basketball.” So it’s like if you don’t love it, you’re not going to work hard. But I think when people watch the beginning, what’s so hard is that he’s doing something he doesn’t want to do. Deep down inside, it’s hard to watch somebody go through that.

JS: I also think on some level, Lenny [preferred to be] the best or nothing at all almost. That’s admirable to me. He didn’t want to be in the middle, so it’s almost great in a way that he’s in broad society’s perspective that he’s nothing.

AS: It’s amazing that he went from the best to not even being like a mediocre journeyman in the NBA. It actually amazes me that he never played a moment in the NBA.

BS: That’s what makes it Greek to me. Still, he can say, “Listen, I was on that rollercoaster.” Not many people get to say that.

“Lenny Cooke” does not yet have U.S. distribution. It plays once more at the Tribeca Film Festival on April 27th at 2:30 p.m. at Tribeca Cinemas 2.