Despite the title “Death By Numbers,” there’s a statistic that threatens to drift by without calling much attention to itself when Samantha Fuentes, a survivor of the mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida mentions in passing that it’s been four years since she returned to the tragic scene, during which time 154 other schools have also been visited by gun violence. When bringing up this number to Kim A. Snyder, she’s quick to correct me.

“When we made the movie in 2022, it was 154, but since Parkland, we did get a number as of the other day,” Snyder said this past week, before going to double check with her producing partner to make sure of the current count, an infuriating 221.

“You just think about every single one of those kids that were killed or injured at the school,” Snyder said. I mean, “One of the most shocking things was when I interviewed students very early on for ‘Us Kids,’ and one said to me, two or three days after the shooting, “We’re not doing well, and there were 17 killed, but there will be more because kids are going to take their lives.” And then of course, within a year or so, three more kids killed themselves at her school. It was just so bone chilling to hear that prediction and then watch it unfold.”

Snyder has been well aware that these are things that are often too painful to talk about, but nonetheless she’s valiantly been trying to help people find their way into a conversation for the past decade, starting with “Newtown” in which she beared witness to the community in Connecticut that came together after the horrific shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary. Her films since have been radiant displays of the fundamental goodness of people in the face of the worst acts some may be capable of, finding the parents in “Newtown” giving each other comfort as they work through unfathomable loss and the students of Marjory Stoneman Douglas take their grief and put it towards activism in “Us Kids.” She hasn’t only put years at a time into embedding at some of the most notorious sites for these tragedies to gain a perspective that can be missed by the local and national news crews that come and go, but she’ll often keep in touch long after, making sure the people who have shared their story with her are cared for and that their stories will continue to reverberate.

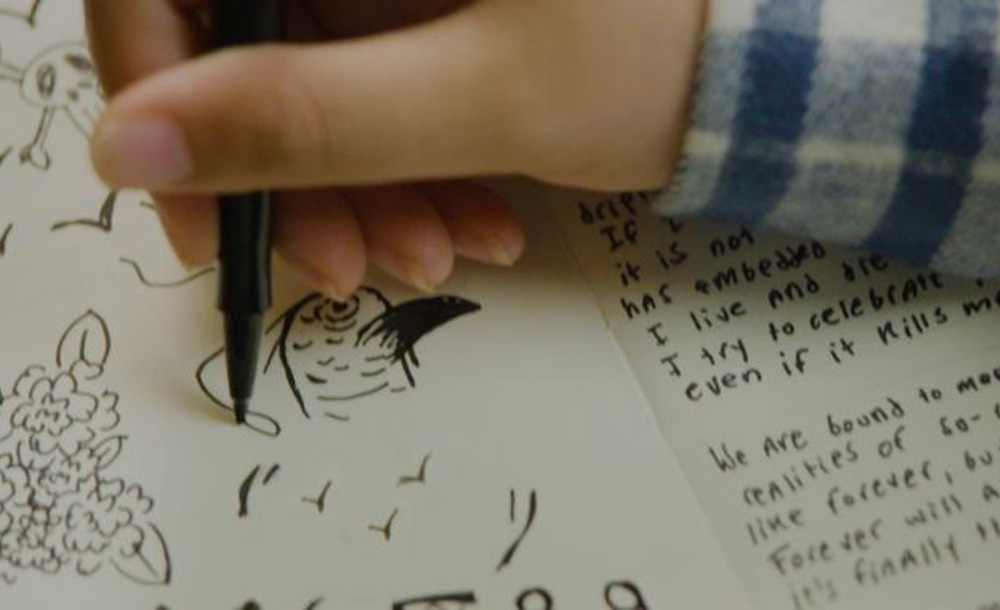

After “Newtown,” Snyder made the moving and unexpected follow-up, “Notes from Dunblane,” which connected priests from the Atlantic Ocean about how best to tend to their flock when such an event occurs, and now with “Death By Numbers,” the director has created a powerful coda to “Us Kids,” trailing one of its main subjects Fuentes through the process of confronting the fellow student that killed 17 of her classmates as his case comes to trial. Snyder inevitably spends time in the courtroom, but Fuentes gives her access to a more intimate space as she opens up the journals she’s kept as she’s worked through her trauma, illustrating the strides she’s had to take to give her the strength to once again be in the same room with the perpetrator to testify and the free-floating anxiety that living through such an event instills. Fuentes, who had once said in “Us Kids” that she used humor and art to cope, is given the canvas for those qualities to shine through, inspiring admiration for her ability to pull through but also questions about why anyone should have to go through this in the first place when there’s been little traction for gun reform at a federal level.

As Snyder was busy preparing her next film “The Librarians” for Sundance, she graciously took a moment out to talk about “Death By Numbers,” which was recently shortlisted by the Academy for Best Documentary Short this year and how her dedication to the subject of gun violence has led to an unparalleled look at the issue from a multitude of perspectives, including that of time.

When I made “Us Kids,” it was a whole cast of students from Marjory Stoneman, and it evolved into a piece that was more about the youth movement that sprung out of shooting. But I was always intrigued with Sam as a person. And it intrigued me to learn this story about her Holocaust studies class that she had taken as an elective. It was a class that was not even specifically about the German Holocaust, but about hate and on the first day of class, her teacher asked this question, “Do you think hate can be eradicated?” And several months after posing that question, it came right into our classroom. I always [thought], “You can’t even write that stuff.”

Then Sam and I developed a very close relationship after “Us Kids.” We just had a very natural chemistry and she ended up moving from Florida to New York, deciding to go to college here at Hunter. It was [during] COVID and I knew, as a friend, all of the travails of working through her PTSD following the shooting and was concerned. I also knew that she was a very creative soul and got a lot out through her singing, her writing and her spoken word. We spoke a lot about her anxiety and apprehension about the trial, which would have happened sooner, but it got very delayed by COVID, and she started telling me about this writing she was doing that she entitled “Death by Numbers.” She hadn’t shared it with anyone, but shared it with me and I was so taken with the words that I thought, “Oh my goodness, I’m sort of done [with this subject], but this is such a different thing.”

I was also really intrigued with the idea that this group of young people were going to be subpoenaed, and that they didn’t really have a choice. All they wanted to do was move away from this as one invariably wants to do out of high school anyway. You don’t want to really return to high school or any part of it, but the worst thing in the world that could happen to you in your end of high school year, you had to be dragged back into it. I was inspired by movies like “Ordinary People” and “The Sweet Hereafter” that were the terrain of trauma and youth too, and I really started to think about it being narrative and scripted, but then we just decided as the trial approached that we should try to document it. We didn’t really know what it would be.

My producing partner Janique Robillard and I spent three months solidly in Florida every day in that courtroom and it was brutal. I had formed relationships with some of the parents of the kids that were deceased. One of them was Nick who died next to [Sam], and those parents had become close with her and close with me, so it was really emotionally very, very rough. We started to envision something that had the ambition of intercutting between the cruel, harsh reality of that courtroom, the trial itself and her having to finally face her shooter, who she had never seen since that day in front of the window of her classroom, in real time and her inner life through her journaling and her feelings, all in an attempt to shed light on the trauma of youth and the ripple effect.

Your films have always been artful, but when they’ve been verite-driven, was honoring the poetry inherent in those journal passages allow you a little more creative leeway?

I really did feel that there was this opportunity to really shine a light on trauma, youth, the fact that this is the number one killer of youth in America and the travesty of that. But I’ve never liked my films to be issue first. I’ve always wanted to push myself as a filmmaker and I do feel that artistically, this film is different than my ones in the past. I was experimenting with new constructs, and then collaborating with Sam was a whole new element.I hadn’t really seen films about gun violence that have a gun violence survivor as a collaborator, and it felt good not only to have her as a subject, but as a writer who was involved in thinking about the music and other aspects and which excerpts of her journals to use.

I feel like I’ve pushed myself further in terms of growing as a filmmaker and I also think that the film is about much more than guns. The film is more about standing up to hate and capturing a feeling in the zeitgeist right now of the normalizing, not just of gun violence specifically, but of hatred. Sam so boldly speaks to just that in both her writings and in that moment of confronting our shooter and the words that she uses [in the courtroom].

How did you decide how to present the shooter? His face is x’d out for the majority of this.

That took a lot of conversation since even before the collaboration with Sam, I made “Newtown” and I’m so close still with so many of those people that I filmed and feel such a solidarity. Part of that is about asking the media to please try to support the idea that we don’t give these shooters any more fame by naming them or showing their images more than we have to, so we really tried to honor that. But I also felt that the point of view was Sam’s and her journaling. That’s why we have the marker and that x’ing out [of the shooter’s face]. And then we have the very conscious choice at the end, when [Sam] finally comes to court and turns her head and looks him in the eye for the first time ever, she is able to reclaim her power by staring him down and because that is her choice, her agency, we felt at that point, it’s up to her to be able to unveil him and be able to stare him down. That was important and she felt that was the right choice.

You have a truly unique perspective on what happens to a community, to individuals and the aftermath of a school shooting because of these films you’ve made. What’s it like to be where you are now and see everything the way that you have from all these different angles?

I do feel I’m in a unique position by looking at different people and different communities because I’ve actually done smaller webisodes that have been in inner cities. [For instance] I was down at Pulse, [embedded with] the Latino queer community. I’ve been doing things that are more general gun violence. And one of the things that you see, especially in the mass shootings, is there is a playbook for what happens in a town. It’s weirdly predictable, emotionally. There are certain just things you see over and over and it’s maddening because there’s this pattern [where] you can’t believe that you’re seeing something that you think can be preventable happen over and over. You know the first thing they’re going to say is “Thoughts and prayers,” then the teddy bears are going to come. Then parents are going to fight over money and who gets what and all these other things. It doesn’t matter what the community is.

I remember the first time, maybe the first big shooting after Newtown, Rachel Maddow saying something like, “One thing that we can’t keep saying is that we’re shocked.” The media has a hard job, so I don’t want to criticize, but it’s just such an odd thing because on one hand, it is shocking every time there’s some news break about big mass act of violence, and yet we all know that we’re inured because nobody can stay this sensitized after something is normalized. Sam was in London with the film last night, and she said that it was really fascinating to her that the audience was asking about the details of ”How many casings and how many bullets?” like they were in shock. She said it really hit home that here in the States, sadly, we are normalizing it. It happens when it happens this often, how many times can you cry? So it’s the opposite of what you want to happen. People become more desensitized because it’s self-protective. That’s the goal, but also the risk of some of these [films I’ve made] is how do you continue to break through the noise? I think you try to break through with really unique voices like Sam.

I feel like I couldn’t make “Newtown” now, because [when it was released] everybody remembered where they were when they heard about those kids. It was such a shocking and horrible thing. Now, it’s not the same. We’ve become more desensitized, though I don’t think the young people [are] because they have to go into those schools every day. They are anxiety ridden and it does affect their mental health. They are afraid of being shot in school. That’s not to say that adults don’t care as much, because parents certainly are terrified, but it’s a chore for all of us to keep caring about something that seems so frustrating and horrifying that we can’t seem to do more about it. There are things we could do, certainly through policy, but we don’t, and we have such dysfunction right now that we’ve got to find other ways to go at it.

“Death By Numbers” is currently on the festival circuit. A list of screenings is here.