Where others saw a gaping hole, Juraj Lerotić saw an opportunity to dig a little deeper. His crew in Croatia had come across a house that would be perfect for a scene in which Bruno, played by the writer/director/actor, would have to run out in front of as part of a frantic search for his brother Damir (Goran Markovic), who has run off after Bruno and their mother (Snjezana Sinovcic) attempt to get him help after coming to believe he’s suicidal. However, they were dismayed to find once they arrived on set that the building across the street had been demolished, leaving a vacant lot they had hardly planned for.

“The assistant from the production came to us and told us we had two problems – one smaller and one bigger. The smaller problem is we have like a big crane which takes the land out, but the bigger problem is we’re missing a whole building,” Lerotić remembers, smiling when he knew it would only add to the drama in a way that no one else on the crew could. “In the end, it was great for us because it works really well. It’s like a rift near the house.”

Lerotić was keeping an eye out for such voids, having felt he was climbing out of one himself by writing “Safe Place” after his real-life brother passed away by his own hand. There was always going to be a bit of projection in the film when Lerotić imagines a failed attempt after which it seems like there’s a chance to save Damir, clearly distraught and uncommunicative, after he’s been processed by authorities and picked up by his family before running off, going through all the ways in which something could’ve been done to prevent the tragedy from occurring, but the film finds its director in the raw emotional space of working out his grief both in grappling with what if behind the camera and placing himself in front of it, an unexpected role that Lerotić takes full advantage of, even powerfully breaking the fourth wall at one point.

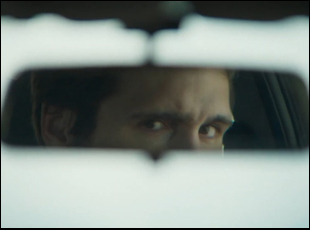

The result is both heartbreaking and invigorating when offering a complete picture of experiencing a loved one cycle through such a desperate moment when any discussion only aggravates the situation, barreling through visits to mental health experts and police who can’t offer much help, yet as Lerotić’s onscreen alter ego looks lost in trying reach his brother, there is the awareness that processing this through his art has to be in some way healing, generously allowing the audience to see what he does as the fog of his sorrow starts to lift. After premiering at the Locarno Film Festival earlier this fall, “Safe Place” has proved true to its title as audiences have found a haven to confront a subject that is so often too uncomfortable to deal with and on the occasion of Croatia making the film its official selection for the Oscars, Lerotić spoke about how he was able to put himself at ease with pouring his complicated feelings into the film and how they shaped the film’s striking imagery, as well as the difficult decision to act in it himself and the occasional bits of luck that made the production that much richer.

Yes, I think you can just ask as direct as you want. We cannot talk about the weather and the movie, it is what it is. [laughs] When it comes to making the movie, I know it could may be sound strange but some time after my brother died, I was in a way fascinated that such a horror is possible at all — that it’s possible that you can lose control so quickly over life that radically without any announcement or explanation someone you love can so quickly disappear. I never had experience with it [before], so to make a movie out of it was not easy because it came from a wound, but on the other hand, it was a little bit like a paradox. I was writing about it and thinking “Oh, I will never do the movie…” and then it ended that I even acted in it, so it’s a little strange.

What ended up pulling you in?

When we were doing casting, we were filming the actors and I was throwing back the lines [from behind the camera] and I realized that I cannot just throw the lines back like a robot. I have to watch my articulation — that was one thing. Then I had the feeling that I had a blind spot because this experience was so near to me that I couldn’t accept the interpretation of an actor. It always seems to me that somehow false or wrong, [even though] the actors were great. The producers and the people around me saw this while I was doing casting, and they told me, “Why don’t you turn the camera on yourself and try it out?” So I tried and somehow I felt comfortable with it. We didn’t know how it would end up because a first-time director and a first-time actor with such a story in the background [was untested], but somehow it was easy. We thought okay, let’s throw ourselves into this and see what happens, and I’m sure that it gives another layer to the movie that I’m playing it myself, but it comes out of the process. It wasn’t intentional.

From what I understand, you don’t really give your actors a full script, but it’s a long process of working out the casting with them. What does that entail?

I did not have such a method that I want to hide the script from the actors, just because it was so private for me in a way that it was hard to give them the whole script. I don’t know why. But I don’t have the talent [where] some directors will call the actors and say, “Okay, let’s do one scene for the audition” and they know it will function. I couldn’t, so I asked them, “Will you do the most important scenes of the movie with me? But really properly [where] we’re not just reading the script. That’s why the process was three or five months’ long and I wanted it at the end where [the other actors] say, “Okay, we’re a family as characters, we really sold it,” and the producers were joking at the end of the process, “Oh, we already shot the movie” because we filmed all the scenes.

What was it like to find locations?

The starting point deciding to shoot in spring to show the beauty of the nature. For instance, in the first shot, you’ve got these concrete walls, but you also have this big tree, so we have this paradox in a way that both an illness can come out of nothing and a beautiful tree can come out of a concrete jungle. Marko [Brdar], the cinematographer, and I were talking about maybe how to make the outer world seem like the inner world of the characters, so we tried different things. For instance, the [production design] department erased all the graffiti from the park to make those giant blank concrete walls look a little bit like a sky, and you don’t know if they are oppressive or is it beautiful. And we took these [small figurines] which architects use in their models – I really love them and when you take them in your hand, they always have bags and stuff like that and you have the feeling of their comings and goings, but it all seems a little futile, all a little pointless, so we wanted to recreate this feeling, how lost they are in the big shots.

We were searching for such spots [to place our characters] and we also try with the choices for lenses and locations to [make it feel like] the characters always caught on screen. They cannot go left or right. It was also important to the locations is that we wanted somehow to look at the characters and create this distance that the viewer has [with] the feeling that the viewer cannot intervene, the same way we could not help a family member. Sometimes I explain this feeling as having to film the family like they are animals — always from a distance, so when we know what we wanted to achieve with that feeling, we went to search the locations, but that was really a long process.

On top of that, is it true you had to shoot around the hours of working hospitals?

Yes, it wasn’t easy because it was also the time after the pandemic, and our producers Vlada Bulimic and Miljenka Cogelja [got] us the permission for five days and then [the hospital administration] said, “No, it’s impossible,” so it was a struggle, but it was important for us that it was real [because] it was strange as a director when you come to a location that it feels like a real hospital and when you’re building up a hospital, you have to convince yourself it’s real. We tried also to find alternate locations, but in the end, all the hospitals in the film are real hospitals.

Did I hear your producer say that the van they drove in the film was the production van as well?

Yes, the car we were driving in [was the same as the characters]. The funny thing is how we found that car was that Marko, the cinematographer, and I were walking through the city and I saw that car and thought that will be a great car [for the movie], so I wrote a message, but it was raining, so I took [a plastic glove, like you’d find] if you are at the gas station, and I put this message inside the plastic [glove] and I wrote in the message, “I know all of this is very strange, but please give us a call if you want to give us the car.” And [the owner of the car] called and said, “Okay, no problem.” So when you’ve got no money, you need to improvise, you know? [laughs]

Really, what I was thinking about was the dramatic structure — is [grief] something linear? Is it something fragmented? And I always think about how Adorno, the philosopher, said how the structure should be a crystallized form, so I thought what is the form of trauma? It has to be something with a rift, so I have to create something very solid — [a timeframe of] 24 hours, very dense — and then try to break the form, the same way the life of the protagonist is disrupted. I like it because you can really watch the film on different levels. Some people can watch it as this voyage of the family or as a requiem about the family because you know that he will die. You can also watch it as a movie about how you deal with your trauma because I am acting it and you learn in that scene that you’re referencing that I am also the actor and the guy who this event happens to.

What I also like is that somehow that in this scene, there’s some love and warmth inside and that the viewer can come back to the scene. I thought it would be a lie to have a happy end, so I didn’t want it to be placed there, but I think you can come back to the scene and think about the scene in the same way I can think about my brother who is not alive, but I have to go back. I was thinking how to disrupt the form — is it voiceover? But that doesn’t seem [overt enough], so when I come to this [idea] that [my character] will look at the camera and say, “Why are we doing it?” I feel that is the clearest way to disrupt the movie. And I [thought], should I repeat [this later in the film], but then it would not be the wound of the film. It would become the tissue and I think the movie is very much about asymmetry and what you give and what comes back [because] we really tried to do all the things we could, but we couldn’t save him, so I didn’t want the form to be symmetrical [where it was] normal then meta and normal then meta, so I wanted really just one [meta moment] in it.

It just hits you in such an unexpected way and part of why it’s so moving. What’s it been like to see with audiences?

It’s crazy. Now I’m in Egypt and it really somehow explodes and it’s strange. It’s strange because to give you an example, a guy came to me after a screening and says, “Congratulations and my condolences.” And people say to me, “It’s so beautiful. I enjoyed it. Oh, I’m sorry. I mean, it’s horrible what happened to you.” So they are in the same position which I was while making the movie. I was always constantly [feeling] the shot was great, but you know that it’s come from something that hurts you. But I really like the range of how people accept the film. They say it’s a movie that everybody should see it, but just once in a lifetime because they were so disturbed. Some other people really see it as a love story [because of] how the love in the family is displayed and some people saw it as a film about how someone can overcome his trauma because I was acting in it.

What I realized recently is that the film takes its shape from the viewer because what we talk less when we talk about hard feelings and trauma is shame. People are often ashamed of their loss and ashamed of the trauma, but people say [after seeing the film] they saw how radically I’m not ashamed of it because I play it, and that somehow encouraged them to open up and talk about their own feelings. It’s really a range of [being disturbed] to these feelings of love and catharsis, so I like it.

“Safe Place” does not yet have U.S. distribution.