After scouring the ends of the earth to make “Chasing Ice” and “Chasing Coral,” braving the Arctic cold and diving into the depths of the sea to capture all that’s being lost to climate change, it was a bit of a shock to the system for Jeff Orlowski to simply set up a camera and let early employees of tech giants such as Facebook, Google, Twitter and Instagram talk in his latest film “The Social Dilemma,” but as it would turn out, the experience was no less harrowing.

“There were times when I spent the last decade of my life professionally going to these really beautiful remote spots in nature and just getting to see all of this amazing wonder on the planet and this film was just so much Bay Area sit-down interviews,” says Orlowski. “I was missing nature while working on the film, but there was a realization that when we had the easy opportunity of all of these interviews, we really wanted to do something more.”

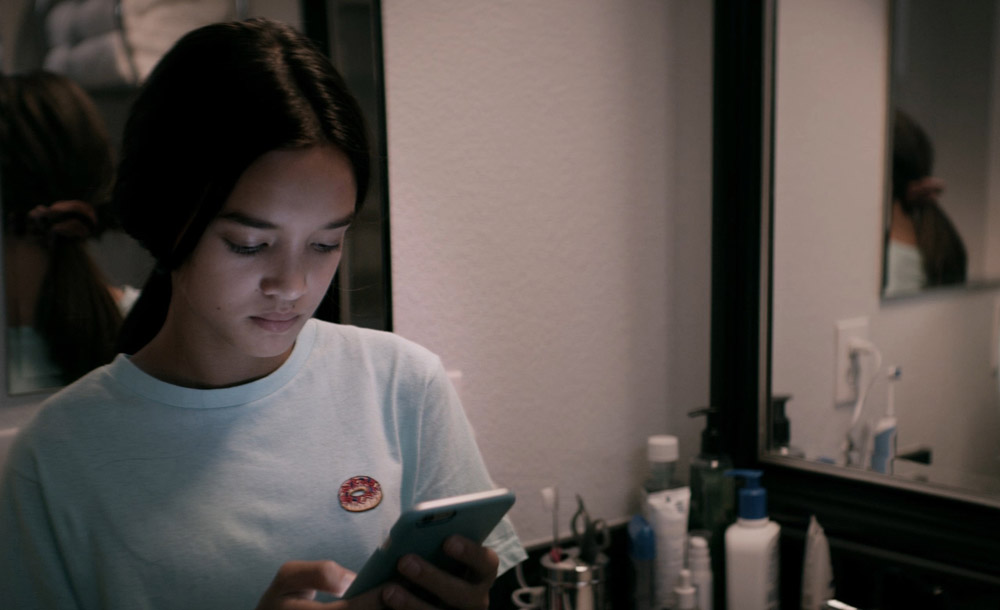

In taking on the pernicious influence of social media in our lives, Orlowski dynamically approaches the online ecosystem of information to find issues that are every bit as rarely seen but deeply felt as the devastation wreaked on the polar icecaps and the coral reefs. The film follows the lead of Tristan Harris, a former design ethicist for Google who has since turned his attention to advocating for greater tech industry regulation when increasing polarization is built into the business models of online giants that have refined their algorithms to influence behavior for advertising revenue, and while a slew of experts are on hand to testify to how subtle shifts have been made to predict users’ actions, the director employs a hybrid structure to show, ironically, how these manipulations are having a real impact in the world, featuring Skyler Gisondo and Kara Hayward as a pair of siblings who are beholden to their devices, rather than the other way around.

“The Social Dilemma” is chilling in its details of how features such as auto-fill have started completing thoughts for people beyond their computers, but continually engaging in its revelations about how people’s attention and habits have been commoditized to the point where advertisers are no longer selling products to people as much as people are being sold as products to advertisers. With the film making its premiere on Netflix this week following a premiere at Sundance earlier this year, Orlowski spoke about getting those with firsthand knowledge of how such powerful tools were developed to track user data to speak on the record, figuring out how to bring together the film’s narrative and nonfiction elements and having to stop himself from adding more to the film when every day the effects of social media on such matters as the upcoming presidential election and the coronavirus outbreak only continue to grow.

Tristan [Harris], one of our main subjects, and I both went to Stanford, and I was working on films about the biggest issues that I could identify and that’s really what brought us to climate change [for “Chasing Ice”] and when Tristan and I were talking a couple years ago, I started learning from him what’s going on with how software is designed and what it’s doing to society. He was calling it an existential threat, and after I learned what he was really talking about — the technology that we interact with and touch every single day is actually unknowingly and invisibly reshaping society — it all really clicked into place for me. I realized there was a huge, huge story to tell here and I just dove in deep.

How did you crack the hybrid structure of this?

That was one of the most difficult things our team has ever done. We had the concept to have these two worlds [of nonfiction interviews and a narrative throughline], but the execution and the challenge of getting them to integrate was really, really difficult, in part because we were still learning just the story from a documentary nonfiction perspective. As we were learning, we were changing the edit and constantly updating stuff. Then every time we would change the interviews, it changed the structure or the order of how we wanted to handle the narrative, so it was a really long and challenging writing process.

One of the things we actually did was work with a storyboard artist to sketch out all of the scenes when we had a draft of the script and edited the storyboard art into the documentary, so you could watch the documentary with a rough sketch of what the narrative would look like. That both gave us the confidence that we could pull it off and then we were modifying stuff up until production and while we were shooting just to get them to work more seamlessly. I feel really good about where we landed.

One of my favorite scenes is where reality breaks into the narrative when there’s a real episode of “Shark Tank” that actually seems to crack a story point for you – were you watching the show and an idea clicked?

No, we genuinely learned from Tim Kendall that he used that [Kitchen Safe, a time-locking container] that was sold on “Shark Tank” for himself — the guy who invented the business model of Facebook basically had to use this plastic kitchen container to keep him away from his phone. That’s how addicted he was. And for somebody who knows how it works and designed it to still need that, it was remarkable, so when we learned that’s what Tim did, we just had to work it into this narrative story and then we found that footage and we were able to integrate it.

It was one of the most difficult things at the beginning to find people who worked inside the companies to talk because we started this in 2017 and it took me a few months of talking with Tristan, [telling him] “This is what I’m thinking. We could do a movie about this.” We had long conversations around what it would look like and through Tristan and his network, we got access to more people who were speaking out. But it seems so crazy to me now that in 2020, looking back in 2018, there were very few people talking about this like this. I didn’t know anybody talking about this critique two years ago and there’s been this really huge shift in perspective. The world is so critical of social media, which is really interesting just to see how people are just understanding more and more what’s actually hiding behind the screens, what’s underlying the software and how they’re actually functioning and operating.

Is there any turn this takes that you may not have been expecting?

One of my favorite interviews that intellectually really pushed me was with Shoshana Zuboff, who wrote “The Age of Surveillance Capitalism,” a real powerhouse book. In talking with her, she makes this comparison — she uses the phrase surveillance capitalism and she compares it to industrial capitalism, saying that what industrial capitalism did to the planet in turning these things into raw resources that can be mined and extracted, that’s what these companies are doing to humanity. Humans are now being mined and extracted for a business model. That just completely shook me, like holy shit, we are the oil that is fueling this trillion dollar industry.

One of my favorite things in the film is when you not only talk to an expert, Dr. Anna Lembke, but also her kids, who may be even more of an expert than her in some ways because of how they interact with social media. What was it like to get both those generational perspectives?

There was a line of Tristan’s that I don’t think it made it into the film, but he said, “We might be the last generation that remembers what it was like before social media took control of the world.” And that’s him as a mid-thirtysomething and as a mid-thirtysomething [myself], I remember a world before social media, but when you talk to a teenager now, this is the only world that they know. It wasn’t always like this and it doesn’t need to be like this, so I think what we’re finding [in terms of] the anxiety and stress that youth are feeling in their day-to-day existence, that was really powerful for us to hear. Honestly, I wish I had done even more of that in the film and talked to more kids because we’ve heard countless really powerful stories, and Anna Lembke’s kids were such a perfect example of seeing somebody who’s a doctor who is studying this and even with that insight and knowledge, seeing how it’s affecting her family as well.

You have no idea. We we were rushing the film for Sundance because of the timelines and we were grateful to premiere there and have the film ready in time, but we had things that we wanted to change after the premiere, so we ended up while we were closing everything with Netflix, we had the opportunity to make some changes to the film. Over the course of March and April, we were making changes and then COVID started and we were just like, “Oh my goodness. We need to get this in the movie somehow.” We figured out how to pull off some changes, but this is one of those [where] with every passing week, there’s more and more news coming out. Just the news from yesterday that Facebook has confirmed that Russian groups are trying to manipulate the election on Facebook and Twitter today, using modified tactics from what they did four years ago, this story is going to constantly be happening. We have a business model that is incentivized for these things to continue and there’s a line in the movie that I really, really love that Roger McNamee says, [where] he says, “Russia didn’t hack Facebook, they used Facebook.” We’re seeing that happen again right now in this election.

It’s terrifying, but is it exciting to get this film out there right now?

I’m so excited because really I feel like this is the issue underlying so many of our other issues. In my mind, it’s the reason why our society feels this way right now — the political polarization and the turmoil — so much of it in my mind ties back to the way humans are getting information. Their perspective of the world is through these platforms and we’ve moved away from a shared reality to, as Roger says, “Basically 2.7 billion ‘Truman Shows’ going on right now.” Each of us is in our own little filtered view of the world and we’re not being given stuff that we ever asked Facebook or Twitter to give us. We’re given stuff that these platforms have figured out will get us to come back and spend more time on them. That’s the challenge. It seems so innocent at first. You see one post from somebody and think, “What’s the big deal?” But when that continues over a decade of constantly being optimized just for you, it’s having these downstream consequences that we’re just now realizing at a societal level.

“The Social Dilemma” is now streaming on Netflix.