Jonah Yoon (Eric Nam) should be careful of what he wishes for in “Transplant,” a supervisor at First Canaan Hospital tries to warn as he attempts to get a leg up on his residency over his fellow doctors-in-training by becoming an assistant to top surgeon Dr. Edward Harmon (Bill Camp). “You are aware who Dr. Harmon is?” Dr. Scarlett Marks (April Grace) asks him after he’s pulled her aside after work to make his case that he’s ready for the responsibility of serving the legendary cardiothoracic specialist, though she isn’t referring to his impeccable credentials, but rather his thorny reputation, which is why there’s an opening in the first place.

The fact that Jonah isn’t dissuaded has as much to do with his medical ambitions in Jason Park’s riveting debut as the fact that he’s likely been told plenty of other times before that he doesn’t fit in as the son of a Korean immigrant who has made it far enough in America to be on the cusp of a lucrative career as a doctor. However, his rise to the top of his profession is bittersweet when the more time he spends with patients, the less he can spend with the mother that raised him (Michelle Lee) and she is in poor health herself, undergoing treatment for renal failure. When Dr. Harmon doesn’t have any bedside manner to speak of, Jonah doesn’t get any sympathy any time he has to scrub in to operate and any time a heart is being put in, it seems like one is being ripped out as Jonah has to constantly balance what is important to him against what he has to give of himself to others.

While “Transplant” itself has the heart of a drama, it is tucked into the guise of a taut thriller when Dr. Harmon’s demands of Jonah start to blur moral and ethical lines and Park doesn’t let up the pressure anywhere for his main character’s when in any realm it seems like he’s dealing with matters of life and death. As a result, the film is as incisive as the cuts made by the surgeons as Park considers Jonah continuing to assimilate into American culture while honoring his Korean roots and whether the effort to serve others will ultimately set himself back to be of no help to anyone. Recently at the L.A. Asian Pacific Film Festival, the director spoke about conceiving of a story that could probe the dualities of being a first gen child in another country, the film’s strong visual sensibilities and watching the sparks fly between his two stars Camp and Nam, who delivers an impressive turn in his first leading role after making a name for himself in K-Pop.

The film was a culmination of several different factors, the first being a Korean-American. A decent amount of people in my community went on the medical track and one of the first things that I noticed about their experience was how brutal and excruciating it was. Initially, it makes sense that medicine is hard. It should be. But it was less about the science and more so about the people, the culture and the hierarchy that existed. I thought that was really fascinating because I don’t think a lot of people know about that and my co-writer and a very good friend David went to Johns Hopkins Medical School, so he had empirical experience of what it’s like to be in that world and the competitiveness. David and myself both had the experience of being Korean-American trying to navigate a space that doesn’t necessarily reflect us and how you maneuver through that but also master it.

Not just professionally, but that idea of code switching or feeling of a place and out of place at the same time as a first-gen son of immigrants is really complementary to the story of this guy finding his footing as a doctor. Did that parallel make it easier to structure?

From the get go, we knew we were going to play these two specific contrasts between the hospital world and his outside home family world. Visually, it was always [the idea] to separate these two places and how it feels, but we knew the story that we were telling was going to be simple yet structured in this in this format because the character is living in only these two spaces. Sometimes it’s hard to simplify because you want to say so much and show so much, but we ultimately felt like the most powerful way of telling the story was to watch this character go back and forth in these two worlds and how they are in contrast but also in some ways do fuse together.

One of the one of my favorite shots in the film was where you move from the floor of the church to the basement, so you can see him in both modes. What was that like to pull off?

We always wanted to do that not as a flashy wonder but as a wonder because we really wanted to capture what it’s like to be at a Korean church post-worship service because it’s so chaotic. It’s so noisy and you’re navigating what feels like the tower of a building. But there’s practical issues of finding a church that has that staircase and the basement where you have a potluck. Filmmaking is all about compromise and that was one of those scenes where I felt we really need to be able to reflect this feeling, and we were able to find that right location. I have to shout out our steady cam op who did a great job of navigating the hallways and the stairs that day and going into a kitchen.

From what I understand, you pulled off the impossible quite a bit, like shooting all the exteriors in a night. How did you do it?

I actually don’t know how we pulled it off because shooting in a hospital setting [alone] is very challenging and difficult, both if you want to use a real hospital or if you want to build one. There’s no cheap alternative. But yeah, we did all our exteriors in one day and it was just what you have to do.

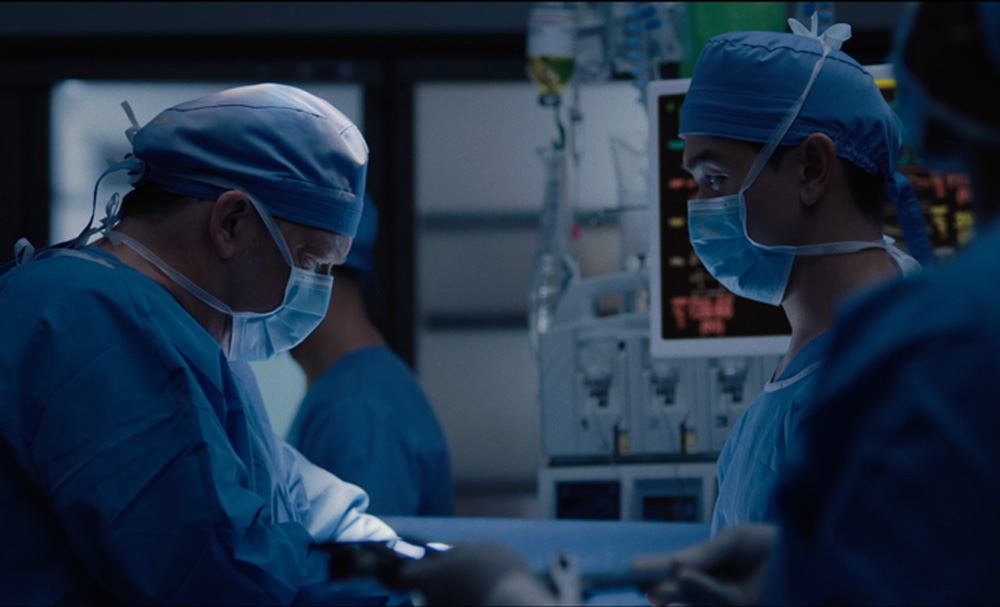

You create a really evocative mood in the operating room. How did you figure out how to film it, particularly the lighting?

One of the goals of this film was to capture how the operating room feels with authenticity and honesty, but we also know that in operating rooms lights don’t just turn off like that [so there’s a dark backdrop], so it’s a little bit of a creative liberty we took. But that was so much about the character and the dynamics and the power that exists [in that role of surgeon]. He’s playing God essentially, so providing this very harsh but singular light source and making everything else feel black makes the space really claustrophobic but also infinite. And there’s this song and dance between these two characters happening, so that all played a part in this big discussion Eric Lin [the director of photography] and I had about how do we make this room feel, especially from Jonah’s perspective because he’s very much going through whatever Dr. Harmon is making him go through. So it was really important was to match that feeling of intensity, anxiety and mystery, like what is going to happen when I enter the space?

What sold you on Eric Nam to play Jonah?

What sold you on Eric Nam to play Jonah?

What stood out with Eric is that he had such great empathy for this character. On paper, he’s a musical artist and he does a lot of different things. He’s very charismatic, and [still] I think people who found out that this film was his first role might have been a little confused. But I think a part of Eric’s journey is this understanding of what it’s like to be an outsider trying to navigate a certain space and to be so committed to a craft where sacrifice is inevitable, so there were many similarities between him and Jonah. Not to say that he is a Jonah, but he understood that mindset and I could see it. And even though Eric is a first-time actor, he is just a natural for the camera. He doesn’t get flustered by it, so all those things made a lot of sense to put Eric in the film.

He doesn’t shrink from Bill Camp either, which is impressive.

That’s hard, right? To me, Bill Camp is a legend. He makes every film better the moment I see him in it and on “Transplant,” he has such a presence and I think a lot of actors, especially if it was their first time, would shy away from it, but Eric didn’t. A part of it is also is that there’s a natural way for a lot of people to play confrontation or matching someone’s intensity, but this story isn’t that. It’s not fighting violence with violence. A lot of it is finding ways to master a space that requires internalization awareness strategy and Eric really embraced that.

What was it like to get the actors together and start seeing the dynamic between them?

As a director, you always have to be very mindful of what an actor is doing and running with it versus trying to be true to the page, and as a writer, I will always have a strong connection to the script. But when you’re on set and you’re watching two humans doing something that’s magical and just feels elevated compared to what was [in the script], you just have to go with it. For example, Eric and Michelle, who plays Jonah’s mom, they had a natural chemistry and I think you can feel just how comfortable and how much of a relationship they had even though they just had met prior [to filming].

You had a wealth of experience before this, but what was it like working on your first feature?

There are some things that are not unexpected and some that are very unexpected. What I took away the most after shooting “Transplant” was as crazy and as much of a sprint as it is, you do have to treat it like a marathon. Whether that means self-care or a sense of sustainability or asking for help, that was part of the education, like “This is not a two-day shoot. This is 25 days,” so you have to find a way to stay energized and have fresh eyes to bring insight to each day, but know the grand vision of it all. There’s a reason why we’re here. There’s a reason why this script works. So finding the core of it while also playing at the same time, those are all of the different things that I learned. No matter how prepared you are shooting your first feature, there’s no experience like it. It’s also a lot of fun and as intense as it was and obviously the film is intense, I remember the moment we wrapped the film, I was like “What’s next. I can go back.” Probably not good for my health, but it’s an addiction almost.

Selfishly, that’s good to hear as a moviegoer. It shows so much confidence as well when you really give the film over to a wordless finale with a great piece of classical music. Without spoiling what happens exactly, was that always how you wanted to go out?

It was in the first two drafts. It was a little different. But I realized there is this beautiful opportunity to showcase this mastery of surgery with letting this whole scenario play out and I love great montages. The most recent one that comes to mind is the “Parasite” montage where you see the father scheming his way with the house help and “The Godfather” [ends at Michael Corleone’s] child’s baptism and he’s getting rid of the five other families. It’s perfect combination of contrast/conflict and thoughts and strategy all coming into one. The trickiest part [then became] what is the music to that, and once I heard that piece, I [thought], “This is it,” to the annoyance of some people because it’s so timed to the edit. Every composition [we tried] has a slightly different rhythm and emphasis, but once I heard that, I was like “This is that version.” It’s always fun to know that that’s coming [as a filmmaker]. I don’t watch [the film now in full]. I can’t. But I do like walking into that part just to see how it plays.

What’s it been like to see the film start to get out into the world?

It’s always a privilege to be able to show a film and have people want to watch it, whether it’s a short or feature, so it’s been both very rewarding and also humbling to finally let go of what has been this journey and to let people take away whatever they’re going to take away. It’s not mine anymore, [which is] a good thing because as as personal and as intimate as making a film is, you know it’s the viewer will take ownership to what they believe this film is. And as a director who is so connected to control, it’s a really therapeutic part of it. This is now anyone else’s who would like to watch it, so it’s been gratifying and great to see the reaction and just watch what it is its own life now.

“Transplant” does not yet have U.S. distribution.