In the run-up to the 2004 presidential election, James D. Stern, with then-filmmaking partner Adam Del Deo, headed to Ohio to tell the story of the Bush and Kerry campaign efforts to get out the vote through the bellwether state in the documentary “So Goes the Nation.” Although the film was objective, Stern makes no bones about his political leanings, the child of Kennedy Democrats from Chicago, which made it especially intriguing when “So Goes the Nation” cast a critical eye on the narrative Democrats tried to paint of George W. Bush, whose shortcomings were so myriad it was difficult to pin down any one specific argument against him, finding that an overall negative impression wouldn’t resonate with voters as much as a single issue that could be used as a lightning rod.

After Donald Trump secured the Republican nomination for president in 2016, Stern could see the cycle repeating again, leading him to quickly mobilize a camera crew to hit states, unlike 2004, weren’t battlegrounds at all, but instead the reddest parts of Florida, West Virginia and Arizona to meet voters that had fallen in love with their candidate. The result, “American Chaos,” is a whirlwind tour through parts of the country that have felt neglected, and while many have traveled there since Trump pulled off the unexpected to understand exactly what happened when polling could not, Stern gets at a story that may be political on the surface, but far larger in scope as it not only reflects the attitudes of those who could justify to themselves voting for such a flawed and unqualified candidate seeking the highest office in the land, but to give a sense of the cultural silos that have been built all around the country in which those attitudes are shaped and go unchallenged.

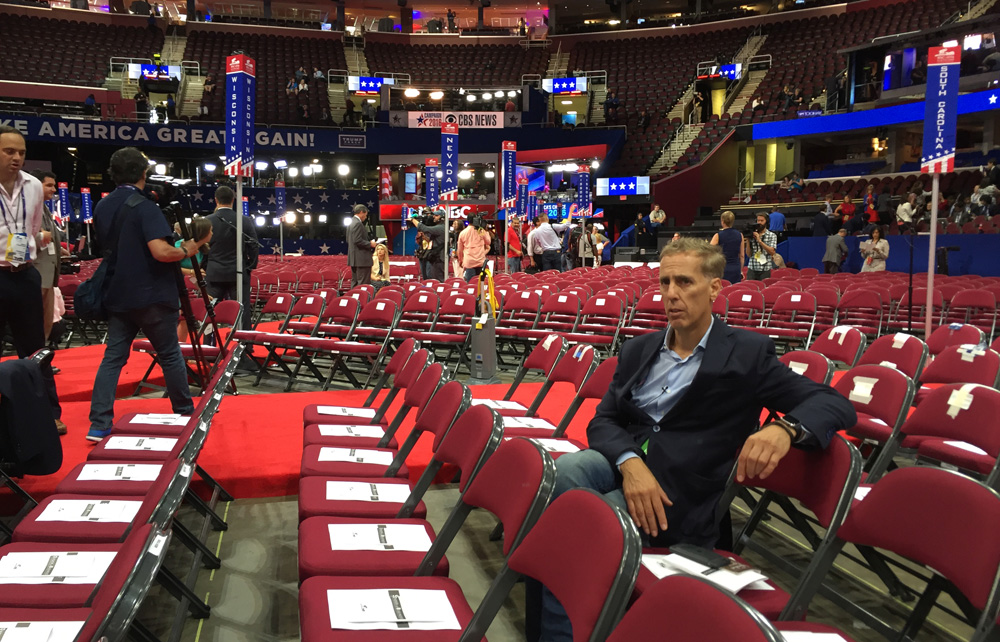

While piercing any number of bubbles, Stern can count “American Chaos” as something of a breakthrough himself, putting himself in front of the camera for the first time after a long career behind it, producing such films as “Come Sunday” and the upcoming “Old Man & the Gun” in addition to his documentary work. His Midwestern pugnacity and respectful tenor proves ingratiating both to interview subjects who might typically be suspicious of those in the media and to audiences as he shows both insight and a sense of humor that allows viewers to actually listen to what’s being said rather than become white noise. Shortly before the film hits theaters, Stern spoke about the impetus to make “American Chaos,” what he didn’t expect to hear on the campaign trail and remaining objective.

I think it was the circumstances, although I continue to be very politically inclined, so it wasn’t out of the realm of possibility. [laughs] I do come from a political environment and family and my own set of interests are so inclined, but I certainly needed a break after “So Goes the Nation” before I ventured into this area again, and when I was watching the nominating process take root and all the people around me were saying that this was the best thing that could happen to the Democrats because he couldn’t win, I thought you’re playing with fire because I thought he could win and in fact, I think he damn well might. I remember telling this to my daughter, who was only 20 at the time and she said, “Oh Dad, you’re just being paranoid. There’s no way that this guy in this year is going to beat a qualified woman,” and as I kept on watching all the talking heads on cable who weren’t listening to each other, but just talking over each other, I said, “The only way to find out is to go out there and talk to people.” The mission of the film was to listen to them – and listen to them with empathy, even if in my particular case not sympathy for the solution that they were seeking but empathy in what their plight was and without judgment – to try and find out exactly what was going on.

Was it much of a decision to put yourself out front and center of this as you do?

It was a big decision. I’ve never done that before. But when I got out there, I felt there had to be a juxtaposition point to these people and to simply tromp around with Hillary supporters wasn’t going to get the job done. It felt personal to me because of my brother, who worked for Obama for seven-and-a-half years on the climate change issue, and because of my two kids.

It was [also] a small crew, just me and my DP really. I’m mapping this out in essentially May of 2016, and we couldn’t be everywhere, and we don’t know Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin are going to fall to the Republicans at that point, but what we do know is that the issue of climate change was going to be a very big issue, which said to me you have to go to West Virginia. From a filming standpoint, it’s quite beautiful and quite different than where I was from, so it created a nice fish-out-of-water [situation] for me to be there.

We always found the people before we went through local Republican organizations. “Hey, we’d love to talk to you, to give you a chance to voice your views and if there are other people who are working in the local campaign that you think are appropriate…that was in Florida, [which I wanted to cover] because so much happens in Florida – this quirky state which has been so rife with controversy, [so that] was obviously the place to begin and to end it also because of Mar-a-lago. Then in West Virginia, I had this absolute desire to talk to the Hatfields and McCoys, if I could, so I went in search of them and was amazed that I found them and David Hatfield said, “Hey, there’s this other person you should talk to.” And then immigration felt like it was going to be a big issue, which took me to Arizona [where] it was like it was in Florida where I got to people through the local campaign.

Did anything happen during the course of shooting that change your ideas of what this could be?

Yeah, what did change was that in many cases, I really liked the people. Certainly not in all cases, and I disagreed with them politically, but I don’t look at the majority of these people as uneducated, unsophisticated and unknowing, and when you come from California, New York, or Chicago like I do, the tendency is to put your views on the people that you’re talking to, which of course they know you’re doing and they hate. But I didn’t understand the issues that they were really going through. In Arizona, where they have people slipping over the border in the dead of night and tromping around on their property, they’re really scared. And I didn’t know that.

Now when somebody says that Islam is not a real religion, that’s a different matter. Then I feel like game on. That’s absurd. And you want to stand up and say you can’t be serious, but of course, the point of the movie is that you can’t do that. You have to allow them to say their piece. There were a couple places where I just couldn’t just quietly observe because what I was hearing was so disturbing, but my role was mostly to be an observer.

You do strike a nice balance between giving the people you speak to the room to talk while not letting them go unchecked if what they say is inaccurate. Was that difficult to achieve?

It was a really difficult balance to strike and it was [only] after I had a cut of the film, honestly. And I felt like I can’t just let some of this stuff go unchallenged and it didn’t feel like my challenging them was in the best interests of the film, so that led me to the next iteration was to seek some of these people out who could speak to these issues directly. It’s an interesting place to put myself because I’m hearing these things that I know are absurd.

When the guy in West Virginia says that climate change is basically a Chinese hoax, and yet he’s also in tears because he can’t hunt and fish because of what he views as unnecessary regulations, not understanding of course that it’s going to be a lot harder to hunt and fish when there’s wildfires raging over the country, [I’m thinking] I have a brother who’s one of the architects of the Paris climate accord and spent seven-and-a-half years in the Obama Administration working on that very issue, so I do turn to the camera and say, “How do I deal with this?” So I ultimately brought experts on to provide commentary because I didn’t want to be the one doing that.

I certainly felt very strongly that it was a movie either way. I wouldn’t have done it otherwise. In one way, it was a cautionary tale. In another way, it was “This is what happened,” but in fact, in some ways, I think it would’ve been much easier if Hillary won because you would’ve had a happy ending. When I finished the film, people thought “Oh my God, it’s so depressing because he won.” But I think that Sony absolutely correctly held the film until people could deal with the issues and deal with them in the face of the midterm elections.

In the wake of Trump’s election, there did seem to be a lot of profiles of Trump voters, trying to figure out what happened similar to this, though this goes into greater depth. Did that influence this or even what happened after Inauguration Day?

When telling a story, whether it’s narrative or non-narrative like this, you have to tell the story that you’re setting out to do. You can’t let yourself get too influenced by the moment that come up because if you do, then by the time whatever you’re doing comes out, or certainly five years later when people go back and watch it again, [that moment] isn’t an issue and you’ve possibly sacrificed the correct arc and story structure for something that’s external, so I tried to very much not to do that and just make my film and let the chips fall where they may.

And nothing happened with the Trump presidency that I did not anticipate. It’s not like I didn’t think it was going to be really bad. I did. You hope for a New York minute that it’s not, and people always say, “What would happen if you went back and talked to people that you interviewed now?” And I always say they’d be completely in favor of everything that’s going on. There’s a certain way where you can think that he’s lived up to his campaign promises as much or more than any president in our memory. All the things he’s doing are things that he said he was going to do. He said he was going to be super anti-immigration. He said he was going to be anti-EPA. He said he was going to overturn Obamacare. He said he was going to be America First and therefore he was going to lead us to trade wars. Everything that he’s done, he’s talked about openly. So I’m always surprised by people who say, “wouldn’t the people you talked to be disappointed in his presidency?” I always say “No, why would you say that?”

It’s great, and I think desperately important. When I did “So Goes the Nation,” the proudest moment that I had with that film was when they showed it at Obama’s convention in Denver and we did a panel with Paul Begala and Matthew Dowd – not that I could get a word in edgewise with those two guys, but it was fantastic. There was a whole discussion of what happened, what could happen and why it was important to rethink it and how it could be different. Now we’re in a similar place because it’s really important that we think about grassroots organizing. In West Virginia, David Hatfield voted for Obama twice, and some of them were never going to come back, but some of them can.

We need to understand who these people are in order to understand how to speak to them. And I think it’s a better solution to treat people with seriousness and with respect no matter how much you disagree with them. To just rail against them only is going to solidify everyone’s position and make things truly a more difficult situation than it already is. You have a man who they think is their friend and is providing a $700 million tax break for one guy who’s then funneling back $30 million for attack ads so that Trump can take care of him again. That’s what they’re up against. America has careened off the rails and the law that gets passed that allowed everyone to be in their own silo and listen to their own information, which happened in the Clinton Administration, has sent us into a place where everybody only listens to their own facts, which creates a position where America is so divided that it’s almost impossible for anybody to talk to each other. This is the worst situation in my lifetime. My mom is 95 and she says this is the worst situation of her lifetime and we have to be aware of that, but I’m very happy that it’s going out now and I’m happy to speak about it.

“American Chaos” opens September 14th in Los Angeles and New York.