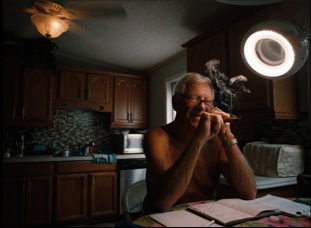

Lance Oppenheim didn’t need to look far for potential stars for his debut film “Some Kind of Heaven” when he was roaming around the Villages in Florida since so many of the people that live in the retirement community had essentially sought out a life that they had seen in the movies. With its perfectly manicured lawns and endless array of activities to cater to any interest, the director had initially thought of attending an acting class to find those predisposed to engaging with an audience, meeting Barbara Lochiatto, who could turn the feelings she had roiling around inside as her husband was dying into something positive, but it was after cameras were already rolling that others started making their way into the frame, whether it was Dennis Dean, who introduced himself to Oppenheim at a singles club as a “celebrity handyman and companion for hire,” or Reggie Kincer, who kept dancing his way into the frame at a restaurant while the director was getting some B-roll and told him he had a premonition of being in his film, ultimately bringing in his long-suffering wife Anne.

As it turns out, any one of them would be worth building a feature around, but “Some Kind of Heaven” is extraordinary for gathering all three for a story about a search for happiness that continues well after they’ve arrived at a purported paradise. Oppenheim, who wryly noted before the film’s premiere at Sundance that perhaps “the older you get doesn’t necessarily [mean] you get wiser,” settles into a place where the pressure to be having fun around the clock so as not to waste a single moment can become oppressive and when people may already be set in their ways, the heightened reality of the Villages has a way of amplifying impulses that there were reasons for refraining from in the past. Certainly, there may be something tragic in watching those arriving at the Villages with the hope that the promised land will wipe away any issues they had before discovering that those may only be exacerbated by their new surroundings, following Barbara and Dennis as they search for a new partner out of different needs or Anne and Reggie dealing with growing apart, but Oppenheim leavens it with considerable humor by capturing the surreal nature of a place where a social club is entirely comprised of women with the first name Elaine and traffic jams can occur between all the golf carts (often customized to look like vintage cars) roaming around.

Magnificent even as its characters struggle to find grace in their golden years, “Some Kind of Heaven” was truly one of the major discoveries out of last year’s Sundance Film Festival and with the film now making its way out to virtual cinemas, Oppenheim spoke about how he created something so insightful and massively entertaining, adjusting to what the film was telling him it wanted to be and how the film’s stylistic flourishes actually drew him closer to his subjects.

I got there and I had no real idea of what I wanted to really make except for that I knew I wanted to inhabit the marketing fantasy dream and call it into question somehow. There’s still a little bit of that institutional portraiture in the film [because] that was the first inquiry that I had. I wanted to look into a survey of all the different businesses, the ones that passed themselves off as privately held businesses, but are actually still owned by the developing family that created the Villages and I was able to weasel my way into some places. I told some people I was a college student, which I was. This initially started as my thesis film and I was able to get some access to some places, but I remember Fred Wiseman had said something about how if he were to try and approach a subject or a setting and they didn’t really give him the access he wanted, he wouldn’t do [the film]. Eventually, the family that develops the Villages found out I was there and they’re very powerful. Somehow they got a hold the sizzle [reel] that I was trying to use to find financiers and convince other people to help me make this film and what ended up happening is they distributed this digital “Wanted” poster of my face and told all the businesses to not only not let me into their establishment to film, but also if they saw me outside at any of the Villages’ premises, to essentially ask me to leave.

So the inquiry turned into a conquest. Everyone was trying to kick me out and making this film there became an act of guerrilla filmmaking because I knew certain locations we would only have 10 or 15 minutes to film before we were asked to leave, so it led to us doing some creative things. Like I went to the Villages Gift Shop and I bought a polo shirt that had a Villages symbol on it or sometimes I wore a construction outfit so it looked like we were doing something official for the Villages, even though we weren’t. Sometimes it would give us a few extra minutes, but it was interesting. The evolution of the film changed quite a bit.

Editorially, I consider Daniel Garber who cut the film with me a co-author of this because he came in a little later after we had done two shoots and completely reshaped the way I was thinking about the film. You’re walking a tightrope act between ogling and looking a little bit less judgmentally at this utopian/dystopian world, and it was my collaboration with Daniel that showed me what the movie could be. After we weren’t really able to get the institutional access that I knew we needed, I knew there had to be another way to look at this very evidently plastic, artificially constructed world in a new way and if you just made a film that was delighting in all the eye candy and all the visual splendor of the utopia there, it wouldn’t be so interesting over the course of 83 minutes. You needed to find some other kind of flavor that could hopefully crack the veneer in a specific way and to me, the most interesting way to do that was not through journalistic expose methods or something that was maybe a bit more of an explicit political inquiry into the place. To me, the most interesting thing was again looking back to some of the marketing videos of the place and looking at how the place advertised itself, inhabiting it and then finding ways to call it into question through the perspectives of these people who didn’t quite fit into it.

These are four real people who have real problems and they’re in this unreal place, so the authenticity of their problems are problems that could exist anywhere, but the fact that they exist in the Villages colors the way you look at the world differently there. From the first shot with the golf carts synchronized driving squad to the end when you see Barbara dancing with the crowd and doing the same kind of dance moves as everyone else, I think there is something interesting that the film is subtly saying about the question of the collective and the individual. If you’re able to subsume part of yourself and give up part of your identity to join this collective vision of retirement that you may find a happier way to live, even if you’re giving up part of yourself to it all. So finding a way to thread that needle and still be as funny as we all wanted it to be, but also hit really hard and make you laugh and make you hurt, that was something that was evident while we were filming it, but also a challenge to balance that tonally.

No, it honestly was the thing we were brushing up against the most. The beginning was the last thing we finished, which is interesting. I knew we wanted to do something where you start in the marketing video and then you crash out of it somehow, but Daniel and I were always hunting for other ways we could start the film. Finally after we locked in the rest of the film and we knew what the ending was and we knew the rhythm and the tempo of everything, a sugar rush is a really good way to describe it. We needed a way to hook people in and sell them on the Villages as your setting that’s worth 85 minutes of your time to watch and then establish extremely quickly a fun, quick portrait of an entire place and then just as quick,go off the beaten path and travel to a road that you didn’t really know existed and then keep going down that road until it forks back to where you were in the beginning.

You’ve also got a wonderful score from Ari Balouzian, which I feel conjures both a richness and a muted quality that extends into the colors of the film or more likely, vice versa. Were certain ideas about the feel of this there from the start?

Ari and my collaboration started well before I even actually stepped afoot in the Villages, and I really like working with him in that way. We’ve now worked together on a few different films and what Ari does extremely well is this Nelson Riddle/Bernard Herrmann orchestral, big, haunted kind of Disney World-y sound and I knew we wanted to do something similar to that effect with this. It’s just him in a room and yet he makes this sound feel so handmade and his music was another thing that was just a guiding principle. It helped us figure out tonally what the film could be. That you’d have these extremely joyous highs of elation and exuberance and then you’d have these lows, and I didn’t want them to be flat-out depressing and hard to watch. I wanted them to have this same kind of richness that the highs would have, so I would want there to be that bass clarinet or a little bit of that texture that would be accompanying the sadness of what it would feel like if you were really upset at a carnival. [I’d wonder] What is the musical equivalent of that?

It was the same way for colors. The image is pretty saturated when we’re in these exteriors, seeing the groups do their thing and this really blindingly bright image that sometimes is a little bit green and sometimes is a little bit garish, but then when you go into the interiors and the interior lives of the characters, it becomes a little bit more muted and a little bit more real feeling until at the end, it becomes a little bit, as our characters more or less, one after the other, conform to the world there, the colors come back up again in bloom.

It absolutely was. Making a short, it’s a really insane thing to do. In my experience, I feel like I have captured moments that do speak to something larger in a short period of time, but the trade-off is the moments where you’re not shooting, there’s just a lot less of that. You don’t have the luxury to put down the camera and talk to your subjects like they’re human beings if something spectacular or something really alarming happens. When you don’t have a lot of money and you don’t have a lot of resources, you just got to do what you’ve got to do. It’s a great medium if you’re not attempting to be anything other than a short, but I do think it’s a challenge when you’re in a place and you’re shooting for only eight days and you’re trying to make this comprehensive view of life.

Sometimes I felt like when I was making shorts, I was there more for doggedly pursuing the making of a film more than a thoughtful inquiry about the subjects’ lives and making this film was completely different. I felt like I cared much more about really the lives of my subjects more than the art of the film. The two ended up becoming inseparable in a way because the film was stylized and we were shooting in a very specific way, our subjects needed to be in on it rather than me just shooting a bunch of random material and just stitching it together in post. There was a lot more attention to detail. We were shooting specific moments that were unfolding rather than just kind of these impressionistic little vignettes in someone’s life or into a community’s existence, so there was a very big difference between the two.

We initially thought this was going to be a short film and then as we kept finding interesting characters and threads and interesting ways to shoot and look at the world, we were convinced we had something well before we knew what that thing actually was, and I think if I was to go into this project thinking, “This is going to be a feature,” I would’ve been very intimidated. I don’t know if I would’ve made the same film and I feel like I would’ve made something less good. I don’t feel I would’ve been as open to a lot of the wonderful things [brought by] the subjects of the film, who were so brave and vulnerable to let us film.

“Some Kind of Heaven” opens in virtual cinemas and VOD on January 15th.