Francine Weinberg Graff knew she was filming something important when she dropped everything in the summer of 1998 to follow her mother Loretta Weinberg’s political campaign in New Jersey as she attempted a move from the General State Assembly where she was a member to be seated as a Bergen County Executive. Known for being no-nonsense, Weinberg captivated reporters who knew she could be counted on for a great quote and her refusal to suffer fools and wait out adversaries led to legislation that had been unthinkable in the Garden State from championing marriage equality to protecting women’s rights and neither she or her daughter could know what a dramatic time she was there to capture when the campaign coincided with a particularly difficult personal time for the family when her husband Irwin was battling cancer, dying only six weeks after the election that she didn’t win.

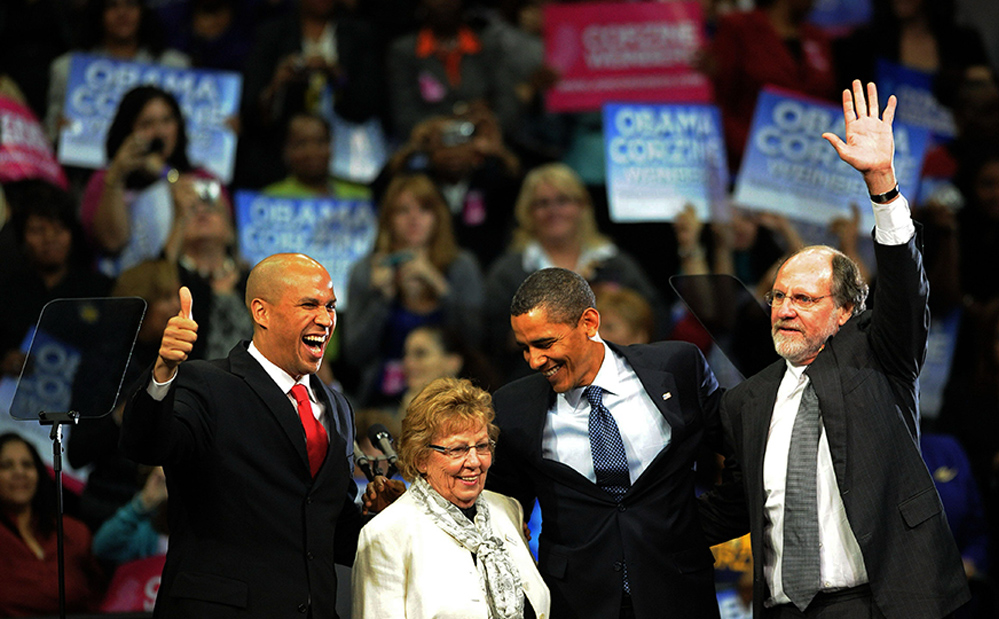

Understandably, Graff put a pin in plans to consider the story done right there and then, especially when Weinberg only entered politics at an age when most are expected to retire, following an admirable life in activism where she was trying to get out the vote rather than collect them. Just as the assemblywoman-turned-State Senator found time to be on her side, her daughter’s patience was rewarded in putting the finishing touches on “Politics is a Mother, Raising Hell is Part of the Job” three decades after she first turned on a camera for the project, having many successes to speak of as she made the decision to retire this past year. All her greatest qualities came to the fore as she bedeviled Chris Christie’s bid to make a serious run for president after serving as New Jersey governor, spearheading an investigation into the scandal that would come to be known as Bridgegate where he ordered traffic blockades on the George Washington Bridge to irritate constituents of mayoralties where he wasn’t endorsed. Once seeing how powerful Christie could be when she was the running mate for Jon Corzine in a failed bid for Governor in 2009, she showed the impact she could make as majority leader of the State Senate, not only holding committees of her own to unearth information about the politically-motivated scheme, but going so far as to attend meetings at Port Authority as a regular citizen to connect the dots.

It becomes clear almost immediately in “Politics is a Mother” that Weinberg wouldn’t have wanted a touchy-feely profile that might be expected upon learning her daughter is behind the camera, and Graff honors her wishes with a film that celebrates her toughness and demonstrates some of its own when it doesn’t pull punches about how Weinberg’s work for the greater good could occasionally make life hard for her family, which offered her support yet couldn’t always reciprocate with the demands of her calling. Still, Weinberg emerges as an inspiring figure when letting little get in the way of serving the public and making social progress. With the film making its premiere this weekend at the Montclair Film Festival, Graff spoke about having a unique view to the life of a politician, playing the long game and looking at her mother in a new way.

This has been in the works… for a lot of decades. [laughs] I say older than my children, who are in college. As I say in the film, I always knew that my mother was different. She was not like the other mothers. She never took us to the park after school. She didn’t go to PTA meetings. She wasn’t a Girl Scout leader. Instead, I spent my girlhood in these old, burnt-out store buildings that they would give to the Democrats for some local candidate rent-free to use for a few months. We were like six, seven and they would drop us off on a street corner in a neighborhood to hand out literature, and pick us up four or five blocks later and we’d run up the street and up and down the stairs of people’s houses. Nobody else I knew was having this experience and even at a young age, I [thought], “This is not like all the other kids.”

Then people would say all the time, “Politicians are so corrupt,” and I would think, “But my mother is not corrupt.” I could see from the inside she wasn’t a corrupt politician, so I would think, “Do you have any idea what politicians sacrifice for you, the general public? It’s time to show what politicians really have to go through.” And because my mother had such a long career, it also morphed into a love letter, [but] not [necessarily] to my mother, because there’s a lot easier ways to do a legacy project. My mother was almost 70 when she became a state senator and 75 when she ran for lieutenant governor with John Corzine. She was almost 80 when she kneecapped Chris Christie and changed the course of history, so this is really a love letter to women who feel invisible, especially older women, and to let them know that you are valued, you have something to offer, and [you can] get into the game.

When you’re telling a personal story like this as a documentarian, was it difficult figuring out what your presence in the film would be?

Yes, and I really didn’t want to make this like a therapy session. I didn’t want to show me or my mom crying, and it’s not who we are. Being around her and the people that she worked with for many years, her staff, it was like a sitcom, and she is funny. She is snarky. She’s a very annoying mother — and she would say, “I am extremely annoying.” She’s very headstrong. So it was definitely challenging. And my mother is somebody who doesn’t like to think about things too much. She doesn’t like to contemplate her belly button and she would say to me and the crew, “Sometimes things just are. There’s not a whole bunch of reasons behind it.” And to a certain extent, that’s her superpower that she doesn’t think about everything.

So what I decided to do was make it a specific journey through my mother’s part in the Bridgegate story, which is very complicated with a lot of tentacles. There were a lot of lawyers who played a part and a lot of very, very good and important journalists, and I had to find a balance with the personal story.

It’s nice how you’re able to bring your father in, who also clearly didn’t want the spotlight, but was very supportive of her political career, which is a story you don’t often see.

As I tweet out sometimes, my father was the original first or second gentleman. He was the man behind the woman. He was the original Mr. Mom. He was the one who took my brother and I to our dentist and doctor’s appointments. I played volleyball, and it was not a popular sport back then, and he would be the only one on the empty bleachers watching me and our team, so my father was really an unsung hero, and probably the most difficult part [of making this] was putting that story in there because it was very difficult for my mother to run for county executive while my father was going through a very serious health crisis. Things didn’t turn out well for him, or for the campaign, which is partially why I put everything away [all those years ago when I began filming]. I was thinking, “What am I going to do with this?” But in the current day, as you see, a lot of those same players from 1998 showed up again in Bridgegate, so I [thought now], “That’s funny.” It’s like a “Saturday Night Live” skit.

Would your mother actually come along on a fair number of the interviews? You see her give Cory Booker a hug after you talk with him.

Mostly not, and my mother doesn’t like accolades. She doesn’t like applause. She doesn’t want to be famous. That Booker interview, she just tagged along. It was in Washington and we planned to interview Sean Boberg [where he is a columnist for the Post after working for the Bergen Record] and [we contacted] Cory, who said, “Yeah, sure. I’ll do [an interview]” and originally, we were going to have them together, but I only had [Cory] for about maybe eight minutes and every single word was poetic. So I didn’t really need [anything else]. But [my mom] has has known him forever she doesn’t give a shit about his celebrity, and I think he likes that he has somebody else he can look up to and who really doesn’t care how famous he is.

Was there anything that happened along the way that changed your ideas about this or took it in a direction you didn’t expect?

The main thing was her revelation in 2018 about being sexually assaulted at 13. That just knocked me off my feet, and I was with her at a friend’s wedding in New Jersey [at the time] and she never said anything. Then I flew back to L.A. and I turned on my phone and there was a text from her that said, “I just revealed my own #MeToo story and don’t call me.” So of course I immediately called her, but she didn’t answer. She loves to text me. She doesn’t want to talk on the phone. And we never really talked about it. But there were a lot of puzzle pieces that came together for me when I found that out and it gave me a real understanding of what has motivated her all of these years. It was the rocket fuel, as my son says in the film, and how she chose to not let the trauma of it overwhelm her so much that she froze in any way, shape, or form with her activism.

What’s it like to just get to this point with the film and start sharing it with the world?

It is fantastic. It’s been a very long, agonizing creative journey and I am ready to birth this child into the world and I feel that the world needs this story to hopefully offer a paradigm shift and to nourish people. Not to be super partisan, but how is this election so close? I want the audience to feel hopeful and to know if my mother can do it, anybody can do it. If you’re really a politician for your constituents and not for the lobbyists or not for the extremists on whatever side, you are not going to get rich and you may not even be that powerful, but you will make change in this world. And that is the reason why I have gone up against every wall possible and tried to find a different way to get this film out there.

“Politics is a Mother, Raising Hell is Part of the Job” will screen at the Montclair Film Festival on October 19th at noon at the Wellmont Theater.