When Stewart Bird and Deborah Shaffer were conducting interviews for “The Wobblies,” they might’ve been a little bit surprised at times to think that in telling the story of the International Workers of the World, they might’ve been making a musical.

“You see the Little Red Songbook, and everyone talks about how important the music was, but when we interviewed Sophie Cohen, she just burst into song,” recalls Bird of how a witness to a 1913 silk mill strike in Paterson, New Jersey summoned the galvanizing battle cry of the workers assembled nearly 65 years later. “And then we noticed that all of them knew these songs and it was part of them, a part of their life and their experience, so we would then mention it to them, and we saw how integral it was to what the Wobblies were about.”

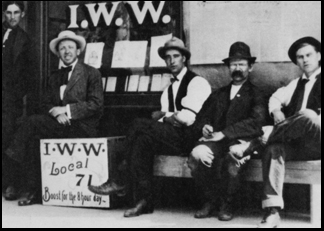

That natural intersection of art and activism could be reflected throughout “The Wobblies,” where it wasn’t just the irresistible earworms that would bring people together in the labor movement that would end up illuminating a history that far too few many people were aware of. In 1977, Bird and Shaffer were racing against time to gather those who were active in the the IWW, nicknamed “Wobblies” for the decidedly un-PC reason of how an Asian worker pronounced the acronym, during their heyday at the turn of the 19th century, fighting for the inclusion of unskilled workers in union organizing to improve the lives of minorities and to build greater strength in numbers. While AFL-CIO President Samuel Gompers dubbed the IWW “a fungus on the labor movement” when they became a threat to his own power, they made considerable gains as indefatigable agitators on all fronts, turning confrontations with management into events that captured the public’s imagination.

If Bird and Shaffer were running around America to get as much first-person testimony as they could from former IWW members, generally no less passionate in their eighties than they were in their twenties, the filmmakers were ahead of the curve when it came to ultimately presenting the oral history, conjuring the energy of historic strikes in Paterson, Lawrence, Massachusetts and Everett, Washington through a pairing for rare visual archival material and a radio drama-esque recreations of events underscoring them that hadn’t been employed before. Combine that with the complaints about corporations such as Carnegie Steel Company dictating unfathomable working conditions because of their market share and the exploitation of foreign-born workers who were scrapping by to survive and “The Wobblies” seems not to have lost a shred of currency since its initial release in 1979, and thanks to a new restoration by the Museum of Modern Art has a crisp image to match as it makes its way to theaters across the country once again for National Workers Day on May 1st. (The Metrograph in New York, in addition to hosting an in-theater run of the film, is also offering “The Wobblies” and an online retrospective of Bird and Shaffer’s work anywhere in the country on their service Metrograph at Home through May 12th.)

Recently, the co-directors spoke about the film having not aged a day, for better or worse, collecting this important testimony before these memories could be lost forever and why there was so much singing in the studio.

Deborah Shaffer: I believe that is why we’re revisiting it. We had applied for a restoration grant in 2003 to the New York Women in Film and Television, who gave us a grant to restore the film. In 2018, they had a screening at UnionDocs in Brooklyn and Stu and I were there and some of the people from NYWIFT and I think we were all shocked at how relevant the film was. I don’t think we all realized that we had made something that was going to [endure like this]. We didn’t intend for it to still be relevant. These problems should be solved, right? People shouldn’t still have to be fighting tooth and nail for a living wage, for an eight-hour day, for bathroom breaks, for health care. It’s shocking and appalling.

And at the time, it was in the middle of the deportations of immigrant workers at the border and [seeing] the whole section in the middle of the film about A. Mitchell Palmer and the deportations of foreign-born workers, it was like, “Wow.” So that led very quickly to organizing the digital restoration, which has now led to where we are today. The film has only become more relevant in the four years since, and with what’s going on at Starbucks and Amazon and other labor unions, I believe unions might be on the verge of a comeback and they’re more needed than ever.

How did the two of you initially come together to make this?

Stewart Bird: Deborah and I were in Newsreel together, an organization formed around the anti-war movement and first women’s films and women’s protests. I was working on a film in Detroit called “Finally Got the News,” about Black auto workers and Deborah stopped by. She was in the area and she saw what we were working on and then we didn’t talk for years. I eventually went back to New York and I worked on a play [“The Wobblies: The U.S. vs.

Wm. D. Haywood et. al.”] with Peter Robilotta, who was working with me at the Mayor’s Office of Veterans Affairs. I was interested in labor history very much and we did the play, which was put on by the Hudson Guild Theater and got terrific reviews. It was sold out and Deborah came to one of the last showings…

Deborah Shaffer: I was probably casting about for a new project [then], but I had been given a book some years before about the IWW that moved me very much about the Lawrence strike called “Milltown” that had been banned in the ‘50s as being too communist. That just completely shocked me – it was about a history I knew nothing about and I had gone through school and knew not one thing about the IWW or their movement. So I went to Stu’s play and a couple of Wobblies that had lived in the area had come that night and they were hanging around afterwards and I just turned to Stu that night and said “We have to film these people.” And Stu says [now] it was hard to convince him — I don’t remember that it was hard, but we did start pretty soon after that. Most of the people we interviewed were in their eighties. A few were in their nineties and a few younger ones snuck in there, but most of them are in their eighties and we knew we did not have time to waste. Our first camera person Judy Irola had a small grant for another film she wasn’t going to do, so she threw it into shooting with us and and we were very, very, very fortunate to get nearly full funding about a year later from the NEH, which funded our production all over the U.S., every corner.

It’s interesting that the Lawrence strike was what may have initially grabbed your attention since it’s one of the film’s most brilliantly devised sequences, roving about paintings depicting the strike as you hear voices describing it. When this must’ve been hard to visualize, what was it like to put together something like that?

Stewart Bird: That’s what we did with everything was mix it and we tried to get original material as much as we could — the paintings of Lawrence at that time and we had a chorus of Italian women…

Deborah Shaffer: It was an editor I knew — Camilla Toniolo, We said, “Can you get some of your friends together and sing these songs for us?” We recorded it in my editing room.

Stewart Bird: And of course, it’s great to have someone like Angelo Rocco, who was standing in front of the mill talking about it. He’s a really incredible person.

Deborah Shaffer: Yeah, he was 94 when we interviewed him and he had driven himself to the interview.

Stewart Bird: And we tried to stay within historical accuracy in terms of the materials we were using. They were usually almost all of the time period and we had an NEH panel of academics checking in on us and making sure. That was good for us and we tried to be as creative as we could.

Deborah Shaffer: Yeah, we were aware we were doing a people’s history, a kind of ground up [chronicle] with the voices of the actual people who had been involved in their experiences, but we felt the leaders were important. We couldn’t just ignore them altogether and they were all long gone, so there was no way we could interview them, so we came upon this idea of using their photographs and actors reading their words, which I don’t think had been done in documentaries before. Back in 1977, a lot of historical documentaries were very boring and heavily narrated, so we hit on this idea because we had the words from Stu’s play, which had the idea to use for the opening and the closing. I remember when we came up with that, we were just thrilled with how it worked in the film, and then found actors to do [Eugene] Debs, [Bill] Haywood and Elizabeth Hurley Flynn. Now, I think everybody’s used to it and it’s done in documentaries all the time, but in 1979, it was pretty brand new.

It’s quite remarkable you get Roger Baldwin, the founder of the ACLU on camera, before his passing just two years after this was released. What was it like to involve him?

Deborah Shaffer: I have a funny Roger Baldwin story because I was talking before about not having an outside narrator, but we cheated on that a tiny bit, I’ll admit it now. We use Roger Baldwin as a kind of internal narrator because there were a few segments that we needed to explain the founding of the IWW and transitions from the mills on the east to the west coast, so we asked Roger if he would read some things for us that we needed to link the different sections together. He was 94 at the time and he said, “Sure.” We went out to his house in New Jersey with a script and he took it from me, and I can’t remember if it was typed or handwritten, but he said, “I wouldn’t say it like this!” and he proceeded to rewrite it. [laughs] Which we used, of course.

He was just so remarkable and really filled the bill as far as being both of the IWW and outside the IWW. And I recently rewatched the film “Reds,” which came out two years after “The Wobblies” and their team was phoning us with research questions and for materials, and if you’ll recall in “Reds,” they use witnesses who speak and comment on the action. Roger Baldwin is their best witness and they borrowed another one from us, Art Shields, who had been editor of the Daily Worker, the communist newspaper. They’re such wonderful companion [pieces] — I’d love to see the two films get out into the world together now.

Capturing that testimony has only gotten more valuable since you filmed it, and and even at the time, you must’ve known how slippery this history was when so many who lived it were getting older. What’s it like to see it have this legacy? I know you even published a subsequent book “Solidarity Forever.”

Deborah Shaffer: I don’t think we knew we were going to be the only ones to ever do it. That’s a responsibility now looking back [that] I’m glad we got most of the things in the film we did, but if I had known then that nobody else was going to do a film about the IWW, think there were a few things we didn’t include I almost wish we could add. But I’m very humbled by the success and the longterm enduring power of the film.

Stewart Bird: And I’d like to mention Dan Georgakas, who died this past year was very instrumental in putting the book together — he was the one who suggested it to us and he wrote the introductions and before that, he also published my play, so he was important.

Deborah Shaffer: And all our materials are archived. They are in Madison, Wisconsin at the State Historical Society – all of the outtakes, all of the interviews, all of the print material. Every little scrap, every frame of film is there and the original negatives are with the Museum of Modern Art, which is how this restoration came about now. But we have given all the materials over for researchers and obviously, it’s a very important legacy.

“The Wobblies” will screen nationwide on May 1st. A full list of cities and theaters is here.