It could come in handy that Chris McKim was profiling an artist ahead of his time in “Wojnarowicz,” even when that would mean a little bit of a wait for his film. Of course, the filmmaker could expect that it would take a while to push a biography of the brilliant and volatile artist David Wojnarowicz, the late rabble rouser whose incendiary installations and performance art drew attention to the AIDS epidemic at its height in the late ‘80s and ‘90s, but he could never have imagined that any delay would often have its benefits, from the year it took to raise financing that put it squarely in sight of a retrospective of the artist’s work at the Whitney Museum, where McKim could grab the contacts for nearly anyone he needed to interview if he hadn’t been able to reach out already, to the film’s postponed premiere, set for the Tribeca Film Festival last April before the coronavirus reared its ugly head.

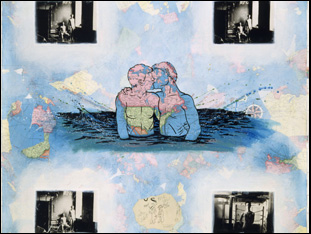

Reaching the masses now, there’s a perspective on a pandemic that we’ve all been living through that is undeniable, but then again that has always been the case when Wojnarowicz was rebelling against a government that failed in stemming the tide of new infections and turning a blind eye to those in need of care when the disease was the HIV virus, known to use the streets as a canvas for stenciled scenes of burning houses around New York City. With Wojnarowicz’s intransigent voice allowed to be heard in full as McKim unearths audio journals of the artist/activist to chart his rise to become a leading voice in ACT UP’s awareness-raising protests and a leading light in the East Village art scene that exploded with the likes of Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat bringing wealthy art collectors down to the Bowery, resulting in a number of strange bedfellows. (As “Wojnarowicz” cheekily documents, the artist was commissioned by Robert and Adrian Mnuchin, parents to future Trump treasury secretary Steve, and repurposed materials from trash heaps around the city to place in their basement.)

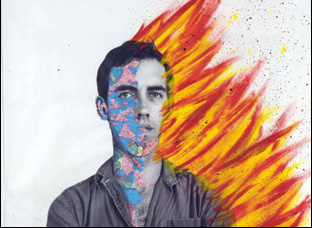

McKim captures the propulsive nature of Wojnarowicz’s work in all its irradiated glory, not only presenting his subject and his art in such a way that doesn’t buffer the rough edges that set him apart but showing how they got to be so sharp, from a traumatic upbringing to the consistent need to respond in kind to a life in which he never received a fair shake. The film honors him in feeling every bit the eruption that one of his works does in its intention to cut through the noise, but that quality is also fitting when “Wojnarowicz” can also be seen as an igniting event for World of Wonder, the production company run by Fenton Bailey and Randy Barbato which has come full circle from parlaying the success of early documentaries “The Eyes of Tammy Faye” and “Party Monster” into shepherding a reality series sensation with “RuPaul’s Drag Race” with enough largesse to now open a new division dedicated to making the groundbreaking documentaries they once were directing themselves when they had the time. “Wojnarowicz” is just one of three projects to burst through the gate, and one of two that McKim directed – the other being “Freedia Got a Gun,” an extension of his work as a showrunner on the WOW series “Big Freedia Bounces Back” about the Bounce music pioneer’s advocacy against gun violence.

In a rare recent break for both McKim and Bailey, the two spoke on the occasion of the release of “Wojnarowicz” in virtual cinemas about doing justice to the uncompromising artist with a film of raw power, the parallels between Wojnarowicz and one of his contemporary firebrands Robert Mapplethorpe, whom Bailey and Barbato had previously made the 2016 portrait “Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures,” and the enduring timeliness of Wojnarowicz’s work.

Fenton Bailey: Honestly, Chris got us excited. Chris, I don’t know what possessed you, but you came to us as someone possessed, really.

Chris McKim: It was July 2017 when the project first got started and it occurred to me in one of my little wormholes that there was this incredible story about this man’s life and I was aware of some of his work, but I didn’t know a great deal about it, certainly not to the extent that I know now. There had never been a film about him. I reached out to PPOW, which was his final gallery, and they managed the estate and set up a meeting with Wendy Olsoff and Tom Rauffenbart, his partner who’s the executor of the estate. Getting their blessing was sort of the first step in all this and then talking to Randy and Fenton and getting them involved and World of Wonder was how this all kicked off.

Fenton Bailey: It was so clear to us the moment Chris walked into the room that yes, this would be great, and partly, I’m not sure if this had any relevance to [Chris], but having done “Mapplethorpe,” he was such a different artist, but at every point along the way, there was a point of contrast. Mapplethorpe had this name that everyone knew. Wojnarowicz had this name that no one could pronounce or spell, and Mapplethorpe’s work was so precise and pristine and symmetrical and Wojnarowicz’s work was cut-and-paste and messy. It just felt complementary in a way. I don’t know if that’s how [Chris] thought to come to us with it at all.

Chris McKim: Well, I think it’s our 300 years of experience together. [laughs] I can’t imagine anyone else being brave and crazy enough to help make this movie.

Fenton Bailey: It was exciting [to cover] that moment in the East Village when artists really exploded and they became superstars and wealthy and famous. It’s almost this turning point of great commodification of artistry, and there’s nothing wrong with that, but what’s interesting is Wojnarowicz was not having any of that. So when Chris came to us, I had a deep down feeling that we were going to be making this on our own. This wasn’t a question of a presale or a big streamer was going to come in with millions. Sometimes films with very angry young men — truly, truly angry young men, not being angry to sell a few more records or a few more pictures — [we had a feeling] we would be making this, financing it solo, but very excited about it because it’s what he deserves. And I cannot think of anybody who’d have made a better film about David Wojnarowicz than Chris.

It’s true to his spirit in how abrasive it is — it’s in your face from the very first moment and there are harsh, but having the same gravitational pull. Was it a challenge to preserve that?

Chris McKim: I can’t imagine ever trying to temper David and that’s one of the blessings too of making something with Randy and Fenton and World of Wonder with all the things I’ve been able to do there over the years. It’s about not pre censoring yourself. It’s about really pushing things to the limits and in the interest of being true to David, that was even more important. I always had this fear that David would come back from the dead and haunt me if I crossed him or did anything he didn’t approve of, so that was a really good motivating factor. There’s a lot going on in the film and it certainly is disruptive and aggressive in ways, but it also has its fun moments too. Things like the answering machine tapes where you can hear the relationships that he had with people in the moment — these sweet calls that he would get from his sister or from Peter Hujar or the panic in [the gallerist] Gracie [Mansion]’s voice as the Mnuchins’ basement is filling up full of bugs, that helped me humanize it as we also make it a little aggressive.

Fenton Bailey: I’m a huge, huge fan of the answering machine messages. Just the whole idea of an answering machine is such a weirdly ‘80s thing too.

Chris McKim: I did an interview the other day, and I realized that the person didn’t understand that David didn’t have a cell phone. They were talking about David being a loner, and it’s like, “Oh, and he didn’t answer his phone,” and I was like, “Well, maybe he just wasn’t home,” but that hadn’t occurred to them.

Still, he obviously had an interest in recording, as you know from all the audio journals he kept. What was that like as a building block?

Chris McKim: We knew it would be a lot of work, just because it is daunting to have to really cover an entire film with visuals without the added crutch or help of being able to cut to people on camera, but it was really exciting knowing that his tapes contained such a journey — not just his feelings about politics and everything, but really kind of trying to find his way in the world. David’s so frequently considered this angry young man, but in the tapes, there isn’t that much of that if only because he’s talking to himself, so he’s not taking it out on himself, but it was really interesting way to immerse myself in who he was. It really was his most intimate thoughts as opposed to just learning about him from all these people who knew and loved and worked with him.

Every day there was some new discovery, just realizing that a certain tape was tied to some moment in David’s life. A lot of it was just trying to find places to put some of our favorite little babies, like some of the answering machine things. David also really collected a lot of sound effects. He taped a lot of the things off his TV and radio, and the street, so just being appreciate the texture in his tapes helped bring the film to life. Because there’s always some car creaking in the background, or police sirens going on down the street, which feels very alive in New York.

Was your idea for this all archival from the start?

Chris McKim: It was. I had never really used archival material that much until working on “Out of Iraq,” which was really just two interviews and lots of personal archive, but I really enjoyed that experience, so I was really kind of hoping for something that would involve a lot of archival work. Even before I knew how many treasures were in David’s audio cassettes, I was aware there was audio available, so I did hope to make this mostly archival, keeping folks off-camera thinking I could use David’s writing as transcripts. It wasn’t long after “I’m Not Your Negro” had come out and that did such an amazing job of mixing not just footage of James Baldwin and his actual voice and recordings, but also using his transcripts, so that’s where I was going and when the audio came from the archive, it was just this huge blessing. I just loaded it up on my iPhone and took a deep dive in all of David’s tapes.

Chris McKim: It was crazy, because they didn’t necessarily happen always at the same time, but we locked “Wojnarowicz” and “Freedia” a year ago in preparation for Tribeca, not knowing that the world was going to shut down March 13, so those last six to eight weeks were pretty insane. It’d be like David screaming in one room and Freedia bouncing in another, which is interesting because as we were finishing “Out of Iraq,” I was getting ready to do another season of “Big Freedia,” so it was the same thing [where] it’d be like Baghdad, and then Freedia twerking in the other room. So Freedia’s always been a good luck charm, and having her music in my mind and in spirit, I think it gives a good editing rhythm.

Fenton Bailey: I’ve been saying this for so long, but I really, really think this is a golden era of docs, and off the back of “Wojnarowicz and “Freedia Got a Gun,” we thought, “Okay, we’ll launch a division,” so we now have a division called WOW Docs — and even more exciting, we have an animated logo. [laughs] So we’re very passionate about it, and I think every bit is important. This may be going a bit far, but I think even “Drag Race” really is a documentary posing as a reality elimination game show, and Chris, of course, was on “Drag Race” for many years.

As terrible a year it was, it seemed like World of Wonder still had a lot of exciting things going on when you have these films and Matt Yoka’s sensational “Whirlybird.” Could you look back with some pride?

Fenton Bailey: It has been a year like no other. I saw an ad for Christmas decorations you put on your Christmas tree, and there were a dumpster with a little bulb in it for a flame, and I was like, “Oh, that’s a good Christmas gift. I’ll order a bunch of these.” And I did. They literally just arrived [in March]. Which I think illustrates the kind of year it’s been. [laughs] It sounds silly, doesn’t it? But [Wojnarowicz] was 37 when he died, and here I am, 60 years old. And after this year, you just thought that, “I have to take a moment and just be glad that you’re alive.” And I am glad. [Wojnarowicz] did so much in that period of time, and when you see that passion and commitment, and I’m just sitting around at home, I don’t have very much to complain about.

And when Chris mentions finishing the film a year ago, I also think Chris was extraordinarily prescient to make this film now. Because Wojnarowicz was talking about this epidemic that the government didn’t really care about. They didn’t really care if people died from AIDS, and with so many respects with COVID, it was very much a similar situation. A right-wing, white male government just didn’t care about anyone who didn’t fit that narrow definition of what Wojnarowicz called “One Tribe Nation,” and unless you are a prophet, there’s no way you could have known that there would be this global pandemic, but it just goes to show how prophetic Wojnarowicz was. Maybe at that time his anger wasn’t fully understood. But now, not just with the Whitney retrospective, but with what has happened over the past year, suddenly his voice becomes so much more resonant. He’s always been the same artist, but I feel that people are going to appreciate it more now more than they did.

Chris McKim: Making it, I was expecting it to come out before the election and I really felt it was really geared towards trying to help fire people up, and I was really freaked out the whole year when it wasn’t coming out. When the election happened, and when the Capitol [was stormed], it does show how prophetic David was because it shows, as Fenton mentioned, the One Tribe Nation and the Pre-invented Existence — it really is about how rigged the system is, specifically to keep these people and white supremacists in power, and how willing they would be to just jump into fascism, given the opportunity. That was always true, but the last year really highlighted it. There had been the assumption that, “Oh, if there were disease that would affect someone else’s loved ones, people might act differently. It wasn’t necessarily about gays and the black and brown people, but their own friends and neighbors.” But the fact is, they didn’t. They were actually worse or as bad as it affected a small niche of the population, which I think is even more frightening.

“Wojnarowicz” is now available to stream via Kino Marquee – a full list of virtual cinemas is here.