You’d think that after sifting through hours and hours of footage of the Broadway production of “American Idiot” taking shape for the new documentary “Broadway Idiot,” the last thing the film’s editor Rob Tinworth would want to do after would be to see the show. But you’d be wrong.

“He came down to Broadway to watch it and said afterwards, ‘Television is such an inadequate medium,'” laughs Doug Hamilton, the film’s director who spent months crouched over a small monitor with Tinworth. “He was so blown away by the scale and the whole event of a piece of theater by being in the room, even though he knew the story. I thought that was a great testament to the theatrical arts and why we need them.”

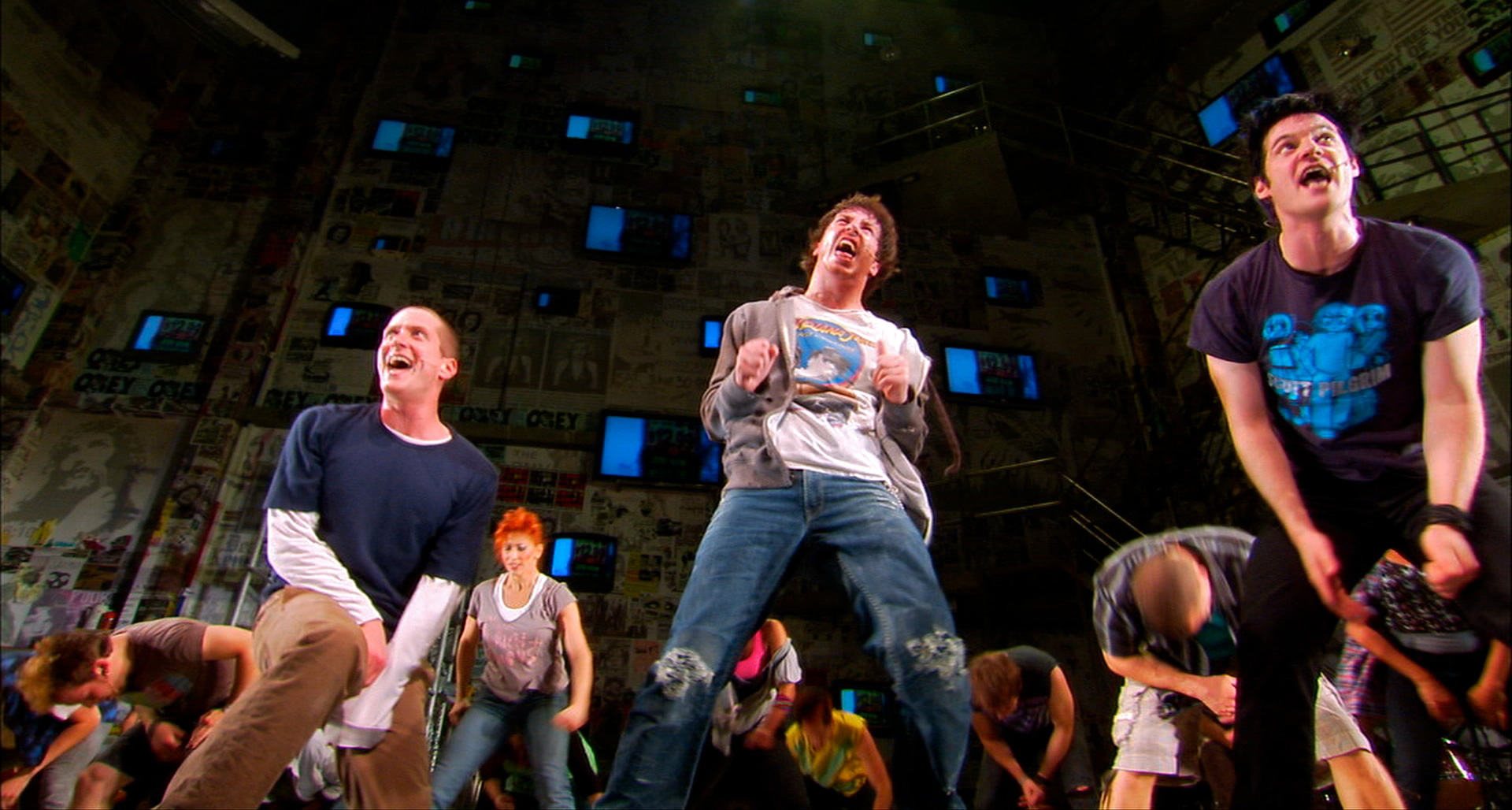

In the same way that the Green Day album on which “American Idiot” the musical was based was a call to arms, “Broadway Idiot” does the same for theater, reaffirming the power of the stage performance in chronicling the blood, sweat and tears that go into every production by taking a rare peek inside the creation of Michael Mayer’s 2010 attempt to bring the rock opera to the Great White Way from conception to completion. Though the band’s punchy punk opus about a generation disinterested in fighting a war they didn’t start and lacking for opportunity elsewhere hardly seemed destined to share the same space as “Oklahoma!” and “The King and I” a half-century earlier, the innovative, relentlessly energetic production featuring breakout turns from “Short Term 12” star John Gallagher Jr. and Rebecca Naomi Jones bucked the odds all in front of Hamilton’s camera.

Yet as much as “American Idiot” changed the thinking about what a Broadway show could be, “Broadway Idiot” shows the way in which the show changed Green Day’s lead singer Billie Joe Armstrong’s thinking about what he could be as an artist. Unexpectedly diving headfirst in rehearsals whenever he could steal away time from the band’s world tour, Armstrong gradually opens himself up to the process of putting the show together and finds a camaraderie and a creative spark that’s clearly as reinvigorating to him as it is to the audiences that eventually bounce out of the St. James Theater. While the film just hit video-on-demand, it is currently making its way to big screens across the country beginning with a run in New York and naturally, to make it feel more like an event, a bunch of one-night only shows on October 15th before expanding into more theaters. To celebrate the occasion, I spoke to Hamilton about the genesis of the film, how he got such amazing access to the production and seeing the walls Armstrong built up as a public persona come down right before his eyes.

One of the things I do is take still photographs of theater here in New York City and years ago, I had worked on photographing the process of “Spring Awakening,” which of course went onto be a big hit. I got to know a lot of the creative team from that and one of the things about “Spring Awakening” is once a show like that becomes a big deal, it’s too late to do a documentary. So when this one came about, I was speaking with Michael Mayer, Tom Hulce and Ira Pittelman, the director and the producers of [both shows], respectively, and we just thought if this becomes what everyone hopes and thinks this could be, it sure would be great if we had been following it.

Were there challenges to doing such a behind-the-scenes film? I’ve read actors unions can be particularly restrictive.

There were and I think we worked very hard with the actors’ unions and the actors themselves and made sure that we were sensitive to everyone’s needs. The rehearsal room is traditionally a very sacred space. It’s a chance for actors to make their rough drafts, to try things out, to make mistakes, to push it too far, to be bad so that they can be good. Normally, that’s been very protected, but here was an opportunity to focus on the process without trying to show the mistakes and to see how something evolves.

When you go to the theater, you have no idea what goes into making a production. It’s hours and hours and hours on the littlest moments to make it all that it is and I love the creative process. In a lot of the films that I’ve worked on, that’s something that always intrigues me, getting inside how people think and create. I wanted this film to do that without just being a making-of, but something more than that.

One of the things that was most interesting was how often you’d actually look away from the action to grab reaction shots. Were you just in the right place at the right time for scenes such as when Billie Joe turned to his wife during a rehearsal of “Last Night on Earth” as if to confirm the show would go forward or did you have an instinct something like that may happen?

The key thing when you’re directing is to know what you’re going after. There are a lot of ways you can go and you have to think well, what are the key points I want to make from this? Actually with that specific one you’re talking about with Billie Joe and Adrienne, I knew Green Day was coming that day and I was talking to Michael Mayer earlier in the day about what he was anticipating. He was the one who brought up this one particular number “Last Night on Earth” and how different it was from what the original Green Day orchestration. So he said, “I just don’t think Billie’s going to know it at the beginning” and in shooting it, I said to my cameraman, “Be on Billie at the beginning of this” because we get the actual performance of this in various ways, but we can’t recreate in any way Billie’s reaction.

It would’ve been shorter, right? [laughs] The way that Tom and Ira and Michael worked with Green Day on this was to structure it so that at several places, Green Day could say we could go forward or not. Michael actually says it in the film, “One of the biggest bands in the world is not going to just say here, take it, do whatever you want with it.” So there were these times that were really important to the future of the show. This was an experimentation for everybody, not just Green Day. Michael, Tom and Ira thought it was a good idea, but they didn’t know it was going to end up on Broadway. They worked in order to make it get there, but sometimes the best ideas you have don’t quite turn out the way you want. There was a realization on everyone’s part that we’ll do our best, we’ll see what it tells us and where the production goes from there. Ultimately as a filmmaker, I am beholden to that. If they had ended it at that point, who knows what it would’ve become? It could’ve been a short little story somewhere. [laughs]

There’s a whole section of the film that’s devoted to how private Billie Joe Armstrong is, though you also see how he opens himself up to the cast and crew of the show and by extension the cameras as the production wears on. Could you actually feel his walls coming down?

I did feel his walls coming down. You know, he’s so famous and he’s gotten so used to dealing with media that in the beginning, he gave us what he knows how to give to the media in that way. But over time, he became more comfortable with me and the camera crews. He fell in love with the process of doing the Broadway show and it was so important to him that I think he wanted to share that experience with the Green Day fans and with other people. He sensed my intention was to do the same thing, so I think he trusted me more and he opened up more and let us in, just like he let the company into this world.

It continued to evolve. In fact, I had actually edited a scene that had some footage of him that I found online where he was singing holiday carols as a young kid. I showed it to Billie and the film was basically finished — it was right before SXSW — and I showed him that part and he loved it, but he said, “You know what? I can do better for you.” I didn’t know what that meant and I didn’t know if it would ever come to pass, but a couple weeks later, he calls me up and says “I’ve got something coming for you.” He had gone to his cousins and got this footage of him singing [something else] and it was just perfect. So it’s an example of how he continued to open up during the process and how he revealed himself in a way that I really respect. I think it’s a testament to what a genuine artist Billie Joe is in his willingness to be vulnerable and his desire to share that.

Speaking of last minute additions, the film actually follows Billie Joe to when he took the stage to play St. Jimmy for a stint on Broadway, which as I recall, came late in the run. Was it a situation where you thought you were done filming and you had to go back?

Yeah, about a year into it. Getting into this project, I never knew where it would lead, therefore I didn’t have any constraints on it either. I didn’t have a broadcast date with a deadline, so it became a question of what this film should be and how long is it? All of those things were dictated by what was best for the material. In the back of my head, opening night would’ve been our conclusion. Then as I was beginning to work on the film and editing it, this amazing thing happened. The film could’ve been more about the process itself, but one of the storylines that emerged was this story of Billie Joe Armstrong and his own experience of [how the Broadway experience] surprised him and seeing how he got pulled into it is one thing, but then to have him actually go on, once that was going to happen, it’s like well, we have to include this. [laughs] It was sort of perfect where the story ended up.

Christine Jones, the production designer on it, had this brilliant concept and one of the things that was very satisfying to me because [while I was editing], I watched this on a computer screen and that’s how I saw the film most of the time and it wasn’t until very late in the process when I screened it large that I realized we had something unique. Showing it in a big room brings something to this that’s special. It looks better on a big screen than it does on an iPhone, so that’s been fun for me and one of the things I’m very happy about is that this is getting a pretty wide theatrical distribution, so a lot of people in all sorts of cities will have a chance to see this in a theater, so I hope it captures some of that magnificent set that Christine designed.

If nothing else, it captures an incredible piece of theater that otherwise only those who saw it on Broadway would get a chance to see.

That’s one of the things that Michael Mayer talks about with this. He’s very proud to have a document of this process. The theatrical process of developing a show is a very, very special thing and it was very unique for me to get to be inside it. To document that and preserve it is valuable, I think not just for this show, but to see the enthusiasm and excitement that goes into making a piece of theater that is one of the main reasons people do it.

“Broadway Idiot” is currently playing at the Village East Cinema in New York, will open at the Hollywood Theater in Portland, Oregon on October 13th and play one-night only in Atlanta, Denver, Detroit, Houston, Indianapolis, Minneapolis, San Diego and St. Louis on October 15th before expanding into wider theatrical release on October 18th. A full schedule is here. The film is also available on iTunes and VOD.