For Donya (Anaita Wali Zada), a feeling of home in “Fremont” doesn’t exactly translate into a feeling of comfort. Resettling in Northern California after working as an interpreter for U.S. forces in her native Afghanistan during the war, she has no trouble finding a place to eat challow made as it was in Kabul when she is among hundred if not thousands who have relocated, but she can only partially identify with the restaurant owner, who wistfully watches Afghan soap operas when he isn’t tending to the grill for his own taste of the old country, when she left feeling unwelcome and yearns for a bit of adventure in her life. As she tells her therapist (Gregg Turkington), she’s chosen to work in the city in part because the transit makes her feel as if she’s getting away, finding work at a fortune cookie factory where even though the labor itself isn’t romantic, the idea of someone being surprised at what they’ll find inside of something she helped make is.

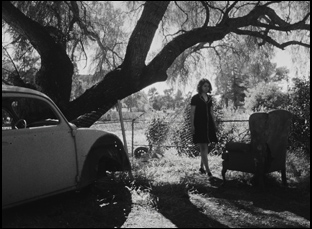

That sense of astonishment is laced throughout Babak Jalali’s utterly disarming comedy as Donya’s search for happiness is constantly delivering it, crossing paths with any number of people looking for it on their own from her co-worker (Hilda Schmelling) who loses herself in karaoke after work or a mechanic (Jeremy Allen White) who fears he gets overly talkative on his lunch break because of his loneliness when he’s on the clock. Filmed in soul-stirring black-and-white, “Fremont” is able to see something special in everyone who appears in front of the camera even if they can’t see it for themselves, making it especially poignant that Jalali found his lead actress Zara after she had to leave behind her own family in Afghanistan and adjust to life in America. With Carolina Cavalli co-writing the witty, incisive fish-out-of-water tale, the film may be about having trouble fitting into new surroundings, but it’s a celebration of community that spreads an infectious joy as the director pulls together a largely nonprofessional cast and crew that he’s built up over his previous films. (For instance, Schmelling, a scene-stealer in “Fremont,” first worked with Jalali as a set decorator on his 2016 film “Radio Dreams,” in which an Afghan band hopes to tour with Metallica.)

Since premiering at Sundance in January, few films have come close to delivering the pleasures of “Fremont,” save for Cavalli’s directorial debut “Amanda” (still out now) and as the film arrives in theaters, Jalali spoke about how he first connected with his captivating lead actress Zada, working with an ensemble from different walks of life and setting up shop in a functioning fortune cookie factory.

I had made another film in the Bay Area called “Radio Dreams,” my second feature, and while making that film, I found out about the city of Fremont. Before that, I’d never heard about Fremont. But I found out it’s home to the largest Afghan population in North America, and being Iranian, we share a language with Afghans and a lot of other cultural traditions, so I went to visit to eat some Afghan food and I found out about the presence of a lot of former translators. Then later on, I read a series of newspaper articles about the way they were living in Fremont and in Sacramento and it wasn’t very pleasant for them. But then, most of the ones that were interviewed were men and I knew there were also female translators, but nobody was really getting something out of them. Carolina and I were in the Bay Area and we went to Fremont to research and speak to prominent translators, and we decided that, we wanted to focus on a female translator and we started writing it.

Once you bring in Anaita, who has a real personal experience to draw on in this regard, did you end up adapting it to her to some degree?

Yeah, because when we started casting for the film, there were almost no professional actresses who are Afghan in North America, so we did an open casting call on social media and community centers. I met a lot of second generation Afghans in their twenties, and then one day, I got an e-mail from Anaita saying a friend of hers had passed on [this casting notice] on social media, and she said, “I’m 22 years old. I left Afghanistan on an evacuation flight five months ago when the Taliban returned. I’ve never acted before, but I’m interested.” So we got on a Zoom video call, and she was just really incredible. She told me she had left her family with her older sister — they got on one of those evacuation flights, but her mother and her six other siblings remained and she had been resettled in Maryland. Although she wasn’t a translator herself, so much of her own personal story was similar to the character of Donya, in the sense of [being] a girl in her early twenties, restarting her life so far away from her country and family, everything she knows. So I wouldn’t say the script changed to reflect that, but definitely her performance was indicative of the fact that she shared so much with Donya. I felt she connected with Donya because she related to her. She knew what that character would be going through.

We actually tried to get Lars to do a cameo in this as well — in one of the fortune cookie scenes where they’re sitting in a restaurant, but he was touring at the time we were shooting. But my previous three films have almost been exclusively made with non-professional actors and the casting here is varied because we have members of the Chinese community in the Bay Area, we have an Afghan immigrant, and this time we have two professionals in Gregg Turkington, who I’ve admired for many years, and Jeremy Allen White, who has become a very successful actor.

It’s a risky thing [putting those different parts together], but you take a gamble on it. I don’t particularly like rehearsing, [or] auditioning either. The process of casting was mainly conversations or getting people to send in videos with a particular theme. In this instance, we got people to send a two-minute video, telling us a childhood memory, just to see how they tell a story or their presence in front of a camera. Having a film of this size, you also don’t have the privilege of having extensive shooting times either, so you can’t say, “Okay, we’ll shoot it and just figure things out as we go along. With this, when you decide to have someone in the film, part of that decision is reliant on the energy that they would bring and the conversations you’ve had with them beforehand about the film, about the script, about the style you want to do [is where] you hope that it aligns. And thankfully for us, they did on this.

When the sparks start to fly on set, was there anything you could get excited about that you may not have anticipated?

I edited the film myself and when you’re going through all the footage of the dailies, you see moments where you don’t remember seeing them on set. For example, in the scenes with the elderly Afghan coffee shop owner, he was just such a character in the sense that he really didn’t want to do this. [laughs] I had to really beg him to be in there because I thought he would be amazing. He worked in a supermarket next door, so he agreed the day before we started shooting those scenes to be in it, and I think there are moments of him where he’s just waiting for us to set up with a camera, but we rolled the camera without him knowing that made it into the film. It was kind of the thing where we rolled just because he looked so good while he was waiting, and if we had said, “Okay, slate this and let’s do this, I was sure it wasn’t going to come out the same way, so you always get those pleasant surprises. I also would like someone like Gregg Turkington because he’s just so intelligent and so original in his whole being that sometimes he says things or moves himself in a way that was unexpected that suddenly you think this is actually better than what we had planned and this makes it into the film.

Yeah, when we were writing this, I didn’t think this would be in black-and-white. It was a decision late in the day, just before pre-production started. I just suddenly had this strong belief that this would work better, and that was born out of [mainly] my gut — there were elements such as the locations we had — the cookie factory — that I just knew it would look better in black-and-white. And Chinatown in San Francisco, even though we don’t show it that much, I didn’t want to make it seem like Donya is going from Fremont, a smaller city into the big city of San Francisco, then suddenly everything is wonderful because there’s lots of color. I wanted to put the two places on the same level, and I think black-and-white also gives it a more of a timeless feeling. In the story, we know where we are because we allude to the return of the Taliban and we talk about the war, but the feeling was that with the locations and with the cast we had in mind, black-and-white would serve us better that way.

Was the fortune cookie factory foundational?

The full credit must go to Carolina on the fortune cookie thing because Carolina and I went as tourists to Chinatown in San Francisco to visit a fortune cookie factory and I was blown away by the visuals. I just thought it was an incredible place. The machinery that they used was the same as they used 50 years ago, so what you see in our film is an actual functioning fortune cookie factory in Oakland’s Chinatown, [which had] the same kind of layout and everything [as in San Francisco]. And they had to continue working while we were shooting.

When I visited for the first time, I just thought of the visuals, but Carolina [thought] it’d be interesting if Donya works in a cookie factory because the film is essentially about the idea of possibilities and she was saying, “Fortune cookie messages are all about possibilities. Some of them are just silly, but some stick with you and they linger.” And she said, “It may be interesting with someone who in a way is lost herself in a new place, and ends up getting the responsibility of providing words of encouragement or wisdom, or giving a shout out to the idea of possibilities to other people, to strangers.”

I was editing Carolina’s film in Italy when I got the call 15, 16 months ago from Marjaneh, [saying] that she was unwell, so with the other producers, we decided to get things moving quickly just so she would know that we’re getting the film made. And as soon as I finished editing Carolina’s film in March, I went over to Oakland and unfortunately, Marjaneh passed away 10 days before we started shooting, so [we were] deep into pre-production. But at least she knew we were getting the film made and her husband Mahmoud Schricker was also a composer and actor on “Radio Dreams,” which Marjaneh produced, so this shoot, was unlike any of other shoots I’ve been on, in the sense that a lot of the cast and crew didn’t know Marjaneh because she was gone before they got to meet her. But they knew what was happening, and they knew the story, and they knew that she went away 10 days before we started shooting.

The whole vibe of the shoot had this sense of [being] a very human, very touching experience, and Mahmoud was with Marjaneh right to the end and when he was doing the score, he put everything in there. He knew what this film meant to Marjaneh because she really wanted this film to be made and she put a lot of her years into it, so I think it felt more than just doing a musical score for him. It was an act of remembrance. It was an act of dedication. And of course I was getting the score as I was editing, so I heard bits and bits and bits, and I was putting it in there and they all fit like a glove because he was so involved in the film from the beginning as well. When we were doing location scouting with Marjaneh four or five years ago, he was there with us. He had read all the drafts of the script. He was very involved in it, so for me it was a very moving experience to hear what he did, but also how he and everyone in the cast and crew reacted to this reality that we had. It really was an added layer to the shoot in the way everyone, including myself, went about getting this film made.

“Fremont” is now open in the Bay Area at the Roxie Theater in San Francisco, the Smith Rafael Film Center in San Rafael and the Cine Lounge Fremont 7 and opens on September 1st in New York at the IFC Center and in Los Angeles at the Nuart Theatre, the Laemmle Glendale and the Encino Town Center 5. It expands on September 8th and a full list of theaters and dates can be found here.