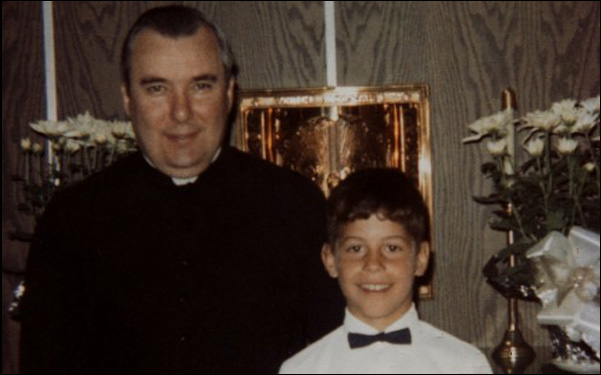

In the eight years since Alex Gibney has become one of the most prolific and provocative filmmakers around, he’s made sport of watching as powerful institutions are ultimately corrupted by human flaws, often by greed or arrogance. But while his documentaries about the downfalls of Eliot Spitzer, Enron and lobbyist Jack Abramoff never shied away from inciting both anger and disbelief, his latest effort “Mea Maxima Culpa: Silence in the House of God” is the director’s most incendiary work to date, tracing the first known case of pedophilia under the auspices of the Catholic Church in America from a school for the deaf in Milwaukee where a priest molested over 200 children during his tenure from the 1950s through 1974 all the way to the Vatican.

Armed with Gibney’s typically meticulous attention to detail as well as his dark sense of humor when appropriate, the film vacillates between the personal journey of Terry Kohut, Gary Smith, Arthur Budzinksi and Bob Bolger, four former students at St. John’s School for the Deaf who refuse to become anonymous victims of the predatory priest and spend decades seeking justice, and the global implications of the Church’s refusal to acknowledge and rectify the widespread sexual abuse in their midst. This past fall, I spoke with Gibney about why he was drawn to making a film about the Catholic Church at this time and his personal connection to it for an article for TakePart, but with the film recently nabbing a place on the Oscar shortlist of nominees for Best Documentary, this is an extended version of that conversation.

How did you get interested in this subject?

I was raised Catholic, so this ongoing scandal was of interest to me. But many films had been made about it or isolated instances of abuse, so I wasn’t sure what I could contribute until I read Laurie Goodstein’s piece in the Times. It was a horrific story, a guy who abuses 200 deaf kids, but it was one in which a very intimate story was connected to a much bigger global coverup and it had at its heart some heroes that we could admire and celebrate. Also, there was something about the central story about these deaf children, which also in a peculiar way resonated with the silence of the church, so this whole idea of this silence seemed to be a grand and terrifying metaphor of this story that seemed to be worth investigating in some detail.

The structure seems so obvious, tracing one case all the way through its trail from Milwaukee to the Vatican, but was it difficult to give equal weight to both the local and global implications of this tragedy?

It was the central problem we faced in making the film, which was how to balance the panoramic with the intimate. It took us a long time to get that right as we showed it to small focus groups and we’re trying to reckon with it ourselves. We had two great stories, but they didn’t seem to be coming together. Sometimes, particularly when you’re making a documentary, to paraphrase Donald Rumsfeld, “Stuff happens” and it happens in unexpected ways. You embrace those surprises and the big surprise for us was this deaf school in Verona. Who knew that there would be such an exact parallel in Italy to the story in Milwaukee? Suddenly, that helped to shape the way the stories mirrored each other in our minds so that you began to see patterns that overlapped. You could see this that what was happening in one place was happening in another and by constantly shuffling the deck until we found the right balance, we were able to come to a reasonable narrative structure that made sense. It always propelled you forward, but each story started to illuminate the other rather than the two stories existing kind of in isolation.

Did your Catholic upbringing give you any particular insight into how something like this could be kept secret for so long?

Sure. I was never abused by a priest, but in the Irish Catholic parish in which I grew up in Cambridge, Massachusetts, there was always a lot of talk, “Oh don’t go back to the sacristy with Father Hamlin because he may grab for you” or something like that. What’s remarkable about that looking back is that was always said with sort of a wink and a nod. It’s not “Oh my God, something horrible’s going on, it was more like, that’s just the way it is. “Father Hamlin is one of those characters and we see a lot of them in the church and you just have to live with them.” [slight laugh] Well, in a way, looking back, that was the most appalling thing about it was that it was so accepted. And it took people like Terry and Bob and Arthur and Gary to come forward, to say no, no, this is really a big, big problem to make us all wake up to what was going on right in front of our noses. This is a scandal that was hiding in plain sight and that’s the thing I took away most about my own experience.

There have been so many of these cases revealed over the years that is has become a bad joke. When public perception already seems to be settled, does that work against you or for you as a shorthand as a filmmaker?

The perception is we know all about this stuff. It’s like a trope. Oh yeah, pedophile priest, know about that one. Check, move on. What was instructive to me about this story was that this stands of a larger metaphor for all sorts of abuses of power. It goes on in the church, but seeing the process, seeing how hard the church tried to protect its reputation by covering up abuse and how a few people ruddered hard to try to get the word out, that was what was so impressive. Again, it’s this idea of hiding in plain sight. In that sense, there’s a lot to be learned, even though the cliché is out there, like oh we know this. We don’t know it. Not really.

Most of your films encounter abuse of power in some way. Was it striking to you that some moments in this may have held parallels to your previous films?

Yeah, it’s true. Look, abuse of power is something I am interested in and so there’s a certain amount of been there, done that, but every time you encounter it, you encounter something a little bit different. I find some corner of that old story that is fresh and new and in this one, it was the idea of noble cause corruption, the idea that because you think you’re good, you can’t do anything bad as a psychological mechanism and also as a mechanism of power.

The film ends on what could be interpreted as a hopeful note in seeing victims of these crimes share their experiences with one another. Were you equally encouraged after you put the finishing touches on the film?

I hope so. If you’re to sit back and think, okay, I’ve made this film, now is the Pope going to apologize to the world, abdicate and set in motion a path of institutional reform? No, not likely. But if you look at what Terry and Arthur and Gary and Bob accomplished in terms of raising the awareness and also actually really getting more information, managing to get documents that show us what’s really going on and then you look at Ireland, you have to believe that’s a positive. As difficult a journey as Ireland has had to go through, you can see how civil society has kind of reasserted itself and demanded justice, a society that for a long time was allowing abuse of power to run rampant under the guise of religious freedom. Those are hopeful things. It is possible to make a difference and I think in that sense the film is hopeful. Pessimistic but hopeful.

“Mea Maxima Culpa: Silence in the House of God” will air on HBO in early 2013.