For years, Alan Rudolph had scant evidence that his film “Breakfast of Champions” existed, despite the fact that it was one of the few he directed for a major studio.

“There was a DVD that was released and suppressed,” says Rudolph of what arguably was his highest-profile project starring Bruce Willis and Nick Nolte in an adaptation of Kurt Vonnegut’s follow-up to “Slaughterhouse Five.” “The only DVD copy I have of it is an old one that I found at Wherehouse Records the day they were closing for 99 cents.”

Made for a release in 1999, now seen as a peak year for cinema, “Breakfast of Champions” was summarily buried by its distributor Hollywood Pictures, a subsidiary of Disney, but if it might seem strange that it was produced and distributed by the Mouse House in the first place, only a month earlier they began to see the slow burn success of “The Sixth Sense” and eager to keep its star Willis happy a year removed from leading the ensemble in “Armageddon.” Willis had previously teamed with Rudolph on the 1991 thriller “Mortal Thoughts” and the director who had shown a mind for mischief with the noir made him an ideal partner for the actor’s ambitions as a producer, pursuing much different material than he was offered as a action star. Rudolph also had an unusual history with “Breakfast of Champions,” which Willis picked up the rights for, having written a draft for Robert Altman to direct not long after it was originally written in 1973.

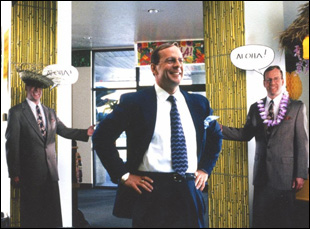

Filmed just over an hour away from Willis’ home in Idaho and the actor himself in charge of financing the endeavor, “Breakfast of Champions” had no studio interference during the making of it, but all the bells and whistles of a proper production, affording a cast that drew up-and-comers such as Omar Epps and Owen Wilson amongst established vets Albert Finney, Barbara Hershey and Glenne Headly, all of whom could run wild playing against type in the comedy set largely at a car dealership where proprietor Dwayne Hoover (Willis) finds himself unable to sell Buicks when he’s no longer sold on his purpose in life. Worried that revealing this to anyone else would upend everything he’s worked for, Dwayne enters the busiest weekend of the year — Hawaiian week at the Exit 11 showroom — a nervous wreck, but it’s soon revealed that he’s hardly the only one having an identity crisis when his fellow salesman (Nolte) wishes he could dress up in women’s clothing in public and so many others are so wrapped up in what the consumer-driven culture is telling them they should be, they rarely give thought to defining themselves.

For Vonnegut, the story was revealing of a moment in the author’s career after he gained a following with “Slaughterhouse Five” and had to reconcile how he saw the world as an outsider and how the world suddenly saw him as a truth teller, with his discomfort manifesting itself into his frequent character Kilgore Trout, whose incomprehensible science-fiction novels finally strike a chord with readers in “Breakfast of Champions” and the author becomes a featured guest at an Arts Festival in Hoover’s neck of the woods, played with great relish by an irascible Finney. It was clearly someone Rudolph could also identify with as he arrived at a point in his career where, for as irreverent as he’s always been, he had enough films under his belt to be a known quantity and wrestling with his largest success to date with the 1997 Nolte/Julie Christie drama “Afterglow.” Given carte blanche by both Willis’ largesse and Vonnegut’s blessing to tell the story he wanted, the director lets loose with an anarchic satire where nothing’s sacred and bold swings such as the film’s score full of animal sounds like the ones that would appear in “The White Lotus” decades later and its visual effects, at the cusp of invading non-blockbuster fare, can be appreciated more for their originality than their eccentricity.

With the film’s rights reverting back to Willis, “Breakfast of Champions” is no longer in the hands of distributors that couldn’t make heads or tails of it and a new 4K restoration is being released by Shout Studios. As Rudolph told me during the press day which he was deprived of during the film’s initial release, I was just the second interview he had ever given in regards to his Vonnegut adaptation, making clear throughout he was immensely proud of it and bewildered by the circumstances it was made under in the first place that allowed him to complete the film he wanted to make and hoping now that it’ll finally get a fair shake.

Well, it’s chapter three for this. It would have been a career killer if I had a real career, but chapter one was writing the screenplay in 1974. Right after “Nashville,” someone had sent [Robert] Altman the book and [he] bought it and he had a couple writers working on a screenplay and nobody knew what to do. He just turned to me one day, and said, “Can you write a screenplay in a hurry? Read the book and write something.” And his only marching orders were, “Don’t follow the book.” I read the book and I could see it was kind of impossible to follow, and I also saw that it would have to be almost a biography of Kurt, because he inserts himself and it’s so personal about his inner thinking about writing and life in America, so I went to New York and met him. This is overwhelming for a young guy, he sounded like Bob [Altman]. He said, “You know, a book and a movie must exist independently, especially my books, so use the book as a point of reference and an inspiration.” So I had permission to do whatever I wanted to with it and rather than chase it all down, I wanted to look at the characters and make a hilarious, corrosive look at America, just like Kurt did, only it’s easier in print, I guess.

Then it didn’t get made. Altman moved on to something else, and I started making my own little films for Bob and that was that. Then David Blocker, a producer who I’d worked with on “Choose Me,” said, “You wrote a screenplay for that. Why don’t we see if we can get the rights?” I said, “Well, I haven’t had any money,” and the rights were available, but at least for us, expensive. We bought a year’s rights, didn’t get it made and let it lapse and a couple years later, I found out that numerous big-time directors had bought the rights to the book, but nobody could get it made. Everyone said it was — I never read the word “impossible” more about anything in my life. They all said it was impossible to translate. It was, I think, something that you felt good to be attached to, but you knew you’d never get a film out of it.

And then I worked with Bruce Willis in 1991 on “Mortal Thoughts,” and he told me it was his best experience and his best acting. He’s a complicated guy and I haven’t had any contact with him for years. I feel for his condition, and we might be opposite politically, but in his soul, he’s a really wonderful, creative, literate, funny guy and very inventive. He called me out of the blue in 1997 and said, “I just — I want to make a really funny comedy. I just bought the rights to ‘Breakfast of Champions.’ You have a screenplay. Let’s go as quickly as possible.” And I said, “Well, who’s going to finance?” He said, “Don’t worry about it. I’ll get the money, but we can’t spend a lot.”

And maybe if I had the money in my hip pocket and I would have financed it myself, I would have taken a year or so and revisited everything, but [what we shot] was just a quick, polished version of what I had written 25 years earlier, and I’m glad it was, even though nobody liked it. And if I had to pick a time to release this movie the way it is, it would be two or three days before this coming election. At the time when Kurt wrote it, it was a more [about] the inequality of life and how we were all trained to be robots in the ’70s and how nothing ever changes because the rich get richer, which is the only story that seems to be true in social existence. But I wanted to peek under the tent of what’s really going on, and to make a really funny movie. And that’s what Bruce wanted and if nothing else, the book made everybody laugh while they’re crying. Now this movie looks pale compared to tomorrow’s headlines, and I don’t know what’s going to happen to it. But it’s chapter three, as I say. Twenty-five years after I wrote it, we made it. Twenty-five years after what you might call technically a release, it’s actually going to be seen.

I probably wouldn’t have ever made it if Bruce hadn’t called out of the blue and look, I’m not supposed to say this, but I am really proud of this film. When I describe it to people over the years, I always say it’s the most reviled film in modern cinema and my proudest achievement because it was so misunderstood at the time. People were so angry because it didn’t literally follow the book, which they also would say in the same sentence is impossible to translate. And when I saw Kurt in the ’90s, right before we made the film, I was living in New York, and it turned out he was a block from me in Midtown all those years. And I went to see him, and he reiterated only in capitals, “Do not try and follow the book. Make it your own. Make it the starting point.” And to me, it was a great reflection on just how dark America really is, unless we get control of it through free will and maybe nurturing thinking like Kilgore’s. Of course, I just love the fact that the most unpublished, nonsensical writer is suddenly deemed a genius, and he can only tell the truth, even if he makes it up.

And Albert Finney, one of our great actors, embodied Kilgore Trout. And I do know that Kurt was thrilled with the choice and the performance of Albert. He brought a soul and a sense of sympathy to chaos and nonsense and I think now people, if they like the movie, it’s because they’re not expecting a traditional literal unfolding of a story. They can accept that there are other factors at play and no matter what anybody thinks of the movie, now or ever, you can’t deny that the actors are really good in this film. The comedic portrayals are slightly over the top, but with an emotional center are really hard to pull off.

Well, I don’t think that way. I think actors can do anything. Actors are – categorically, at least – the only true artists in the process. There are writers, directors, cinematographers, and craft service people, but the stats are going to show you that most actors are true artists, and they have no choice. They’re so complicated and so vulnerable and what they do for a living is astounding to me. It’s like alchemy, that they can take that part of themselves and find the part of a fictional character and put themselves in that place and then behave as if that character is real and dimensional. And I have never gone after the traditional way of telling a story because I’m interested in details that add up and I always wanted to do it differently and add up to the same thing. Altman was always interested in what it added up to and then went into the details, and my whole thrust, maybe not so much on “Breakfast of Champions,” was I would like the audience to respond emotionally more than from a storytelling point of view, just find some connection that even they don’t understand with the characters and the characters’ behavior.

If you boil it way, way down to the most basic reason why you work with anybody or why you go ask them to work with you, which is more the case, is because they want to do it. They want to explore. They want to break the patterns. And a guy like Nick Nolte – there is no guy like Nick Nolte – I don’t think you could find any actor that qualified as an international star and a franchise player as he was with “48 Hours,” and he turned down everything – he told me he turned down “Die Hard” – and took a chance and did a low-budget, so-called independent film when he did “Afterglow,“ which we made in ’96. And Nick, who was really known as a serious actor, a tough guy, an action guy, an all-American – he’s hilarious in “Breakfast,“ and we did a couple of little movies after, and they were all comedies. It didn’t start out this way, but it grew because I just think humor is the way in. If people can laugh at things but not know why they’re laughing, and it’s still a dramatic thing, then I think we’ve entered new territory where we’re all equal. And Nick was as funny as anybody. I always watch actors right next to the camera. Thankfully, I never had to look at them through electronic video shit. I would just always stand right next to the camera. And Nick would make me laugh sometimes so much during a take that I’d have to stand back. And every one of them did.

I’ve never really worked with computer technology. I guess I got out in time. It’s still about the people, and it’s outrageous, but not so much as it was at the time. And the visual effects that we had then were real primitive because this was made before the Internet and before the computer technology took over, and Janet Muswell was our VFX supervisor. She’s probably gone on to bigger things, but we were inventing the cheapest way to do those things, and we had to make almost all the commercials in the movie. Do you know what product placement is? Everybody comes to you when you’re making a movie, little or big, and says, “If you’ll put this bottle of ketchup in the foreground, we’ll give you some money.” Producers always want to do that, and I never allowed it, ever. And a few times it snuck in, I was furious.

But [in this story], I took advertising as the mortal enemy and tried to focus the film through that. I said to David Blocker, the producer who I’d worked with many times before, all that product placement that you always want to put in, I want you to tell everybody that “I will put their commercials on film. I’ll put products in the foreground. I’ll have the characters talk about it.” And he said he was drooling. He sent it out to whoever the product placement people are, and they got all excited, and they sent it to the companies who all read the script and refused. So we had to make our own commercials, and we had to take the names off of the cars. They wouldn’t even allow us to do it. The few commercials that let us use their, and the few companies that let us use their commercials, they’re in the movie.

The Barbara Hershey character, the wife who follows advertising and television commercials in which her husband stars, is dead in the book. She committed suicide by drinking Drano. And I didn’t want to do that. I approached the character as if she might still be alive, but you could remove her from every scene, so if you looked at it that way, that she may or may not be there, it doesn’t make any more or less sense, but it could be that she’s just a vision, and Dwayne’s talking to himself anyway. I wish I had done one thing at the end to just hammer that home, but that’s the next 25 years when “Breakfast” comes out again. I’ll do it.

Are you surprised by how timely it seems now?

Maybe people are ready for it now, but I really think it’s a quality piece of work that needs to be seen. The story I set out to tell was about a guy who finally realizes, whether consciously or not, that he ain’t what he thinks he is and he hasn’t got the inner capacity to figure it out, so instead of generating it through his own being, he has to search for an answer from someone else. And of course, the guy who only spews nonsense to everyone is the one who’s gonna tell him the truth, but then he misinterprets it. I did tell Bruce before we started shooting, “This guy, Dwayne Hoover, is a symbol as much, if not more, of politicians than anybody else who basically promote themselves and become successful through avoiding telling the truth and get a big, inflated version of themselves that is based on fame and financial gain.” [He always says] “You can trust Dwayne,” and none of it’s true. People who are manipulating you to think you’re in good shape aren’t behaving in your best interest. And you can only figure that out if you maintain the most fragile, important thing you have, which is your own identity.

I hope somebody likes this movie. I mean, you can’t hurt me anymore with it and I’m just thrilled that the ushers in the theater may see it, if nobody else.

“Breakfast of Champions” is now showing at Alamo Drafthouses across the country as part of the theaters’ Alamo Time Capsule 1999 series. You can see locations here.